Saproxylic beetles

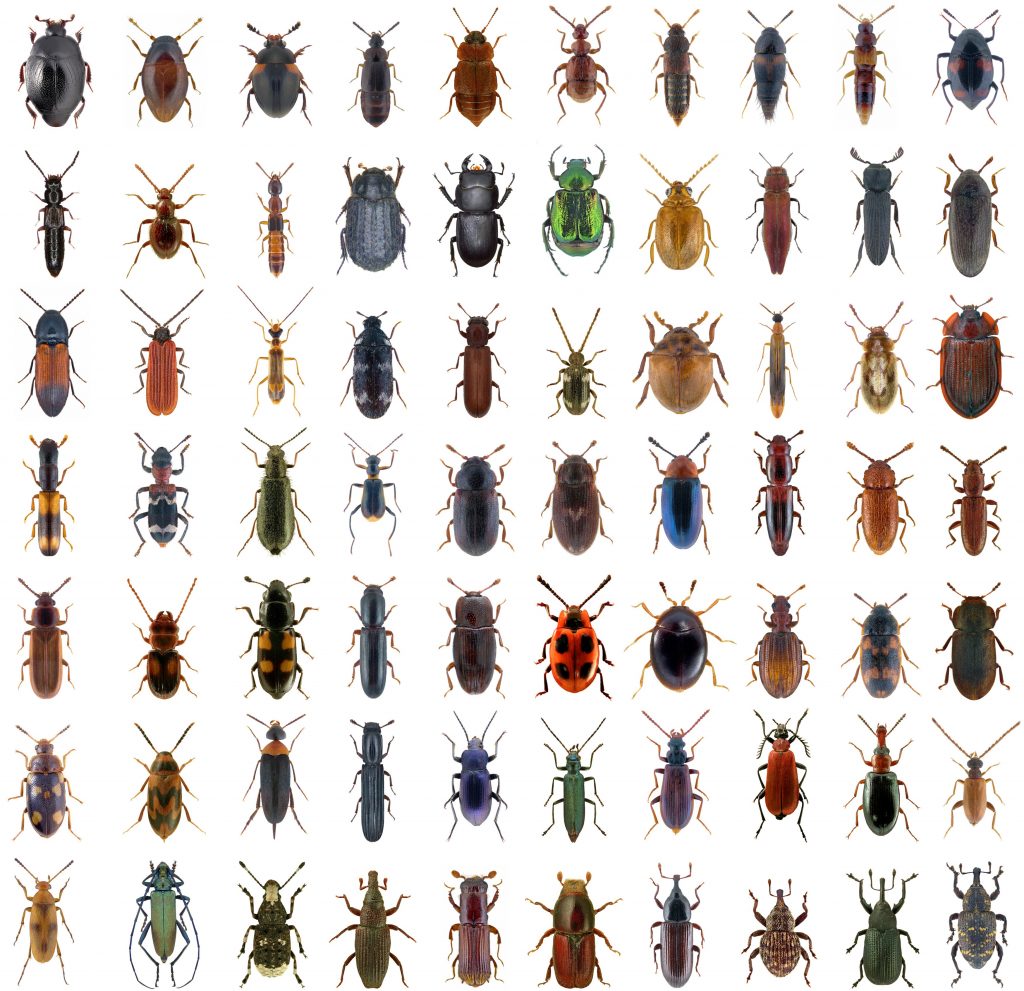

Beetles, beetles, beetles. I love beetles and one of the best places to look for these animals is in and around deadwood. This often overlooked habitat positively bristles with a splendid variety of these insects.

In the UK, where insect diversity is relatively meagre, 650 beetle species representing 53 families depend on deadwood. Some feed on the wood itself, but many depend on the varied fungi that feed on the wood or the fine wood mold that accumulates in the rot cavities of standing trees. Still more are hunters, feeding on the species that nibble the wood and fungi. There are even some that are free-loaders in the nests of ants and wasps that make their nests in dead and decaying trees.

These species and their habitat are ripe for discovery too. On the whole, the biology of saproxylic beetles is very poorly known. Exactly where they live, what they eat and who eats them is often mystery. The first step in answering some of these questions is being able to find them and reliably identify them.

Beetles and woody material go back a long way, probably to the very beginnings of this group of insects. The first beetles may have sought refuge in woody material that fell into freshwater and from there they evolved to exploit this resource. Much of the extraordinary beetle diversity we see today is rooted in this habitat. Indeed, a large proportion of living beetle families are associated with woody material for most of their life cycle.

Two very ancient families of beetles that are still with us today – the Cupedidae and Ommatidae – are associated with deadwood. Neither of these families are found in the UK, but they give us a glimpse of what the earliest beetles may have looked like and how they lived. These extant beetles share many similarities with the oldest known beetle, Coleopsis archaica, which was described in 2013 from the earliest Permian of Germany.

Middle – Ommatidae (Omma stanleyi). Image by Cai and Huang 2016

Right – Reconstruction of Coleopsis archaica gen. et sp. nov. (Tshekardocoleidae), holotype, ZfB 3315. A, part, body, dorsal; B, part, ventral. Image from Kirejtshukab et al 2013.

For more information take a look at this recent paper on the evolution and genomic basis of beetle diversity.

With all of this in mind, the tragic thing is that this hyper-diverse and fascinating habitat is often overlooked, even destroyed. Standing dead trees are chopped down and branches and trunks on the ground are often cleared away, chipped or burned or stacked in neat piles.

Recently, I’ve been using interception traps to study these insects in more detail. The design for these traps was kindly supplied by Adrian Dutton who also gave me some tips for putting them together. The cheapest supplier of 3mm transparent acrylic I could find was sheetplastics.co.uk, although you could use other material. The panels can be attached to the funnel and the top cover with cable-ties (ideally reusable ones) or wire and can be assembled and disassembled in the field. This way they can be flat-packed and transported easily, even in a ruck-sack. The collecting bottle lid can be attached to the funnel using a hot glue gun or with thin wire threaded through holes made in both parts.

These traps are superb because they can be left in situ for a month at a time and you can sample the beetle species without destroying the habitat. Many of these species are very difficult to find otherwise. The larval stage may be spent in more-or-less inaccessible microhabitats and the adults may be very short-lived.

Left: Interception trap. Beetles and other insects fly into the transparent acrylic vanes and fall into the collecting bottle that is filled with preservative.

Middle: An interception trap on a standing dead beech.

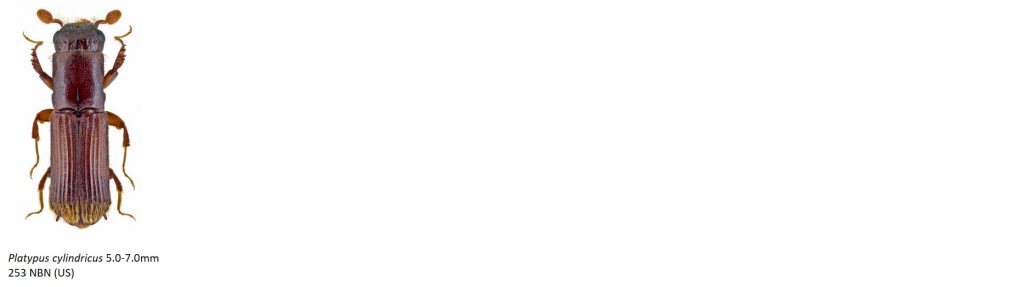

Right: Cleaned June-July sample from the trap shown in the middle photo. Debris and other arthropods have been removed. Letters indicate the following: Ec – Eucnemis capucina; Lm – Laemophloeus monilis; Ts – Trichonyx sulcicollis; Ar – Ampedus rufipennis; Ln – Lymexylon navale; SS – Stictoleptura scutellata; Pc – Platypus cylindrus (many specimens in this sample).

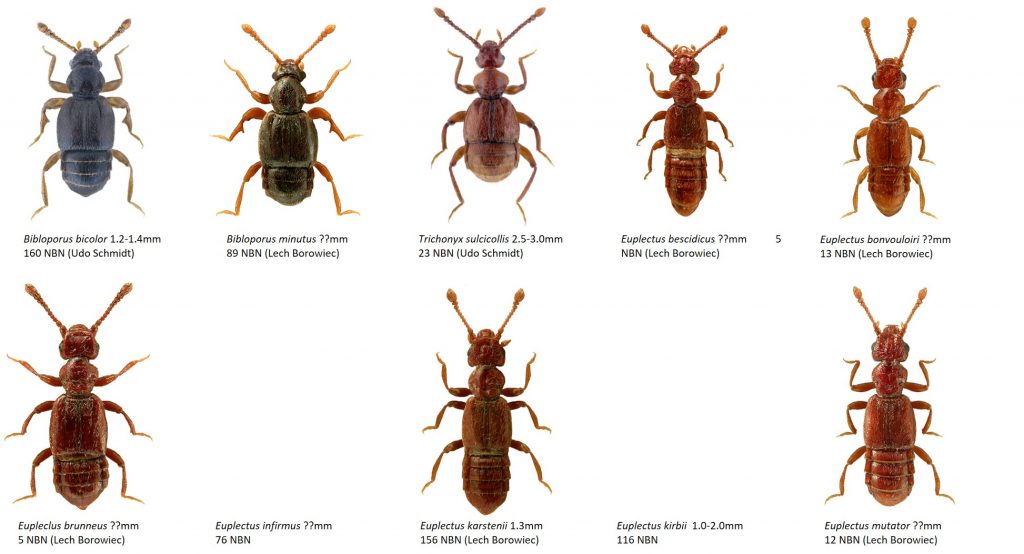

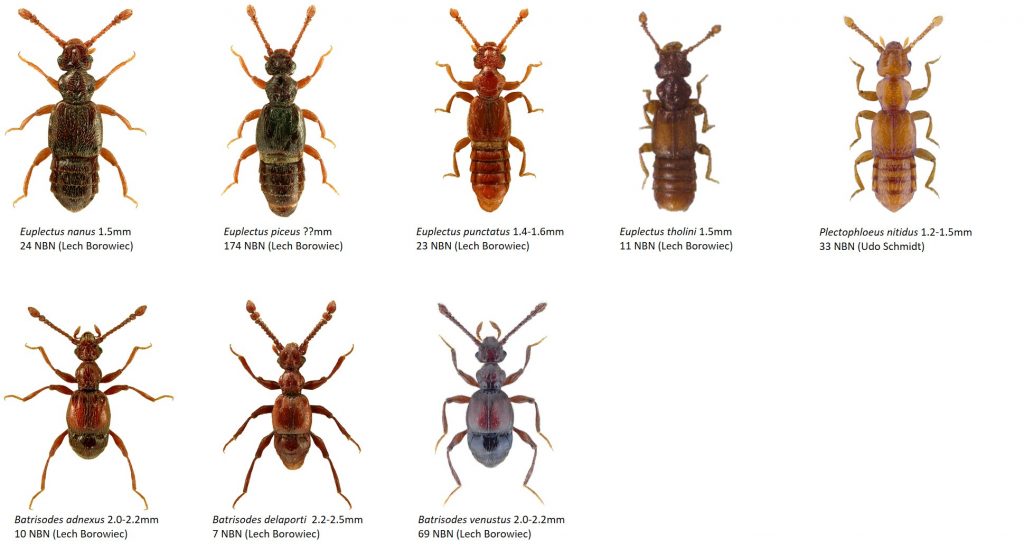

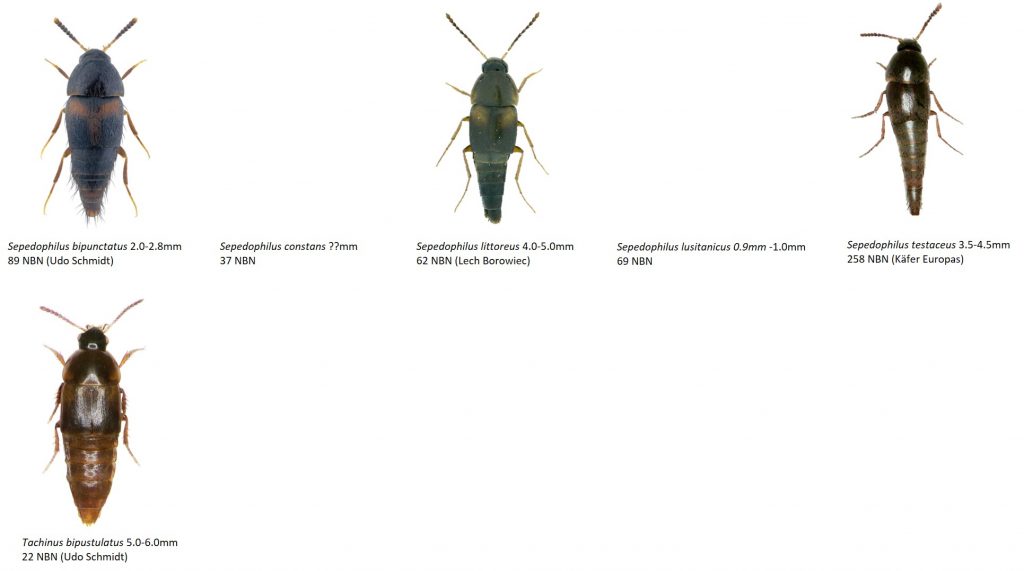

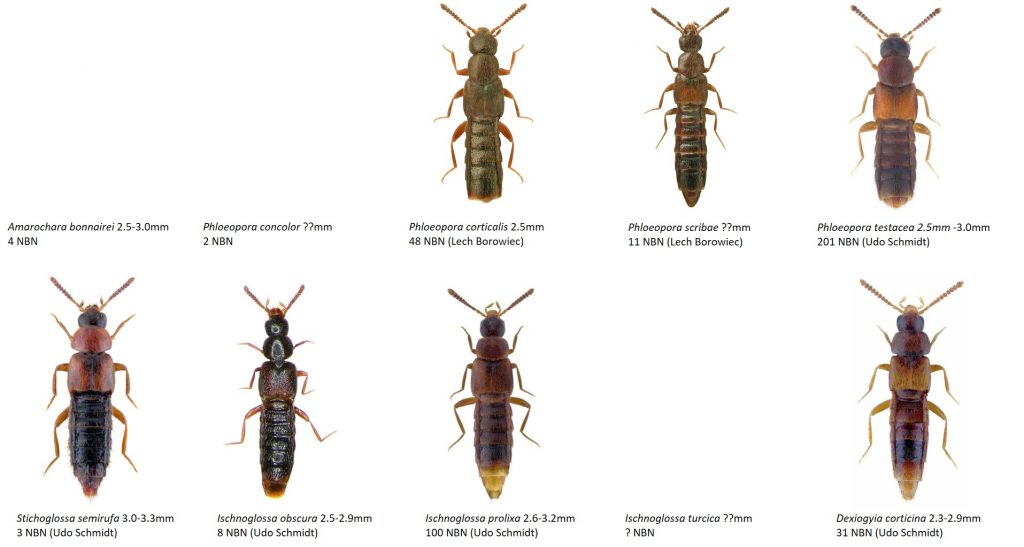

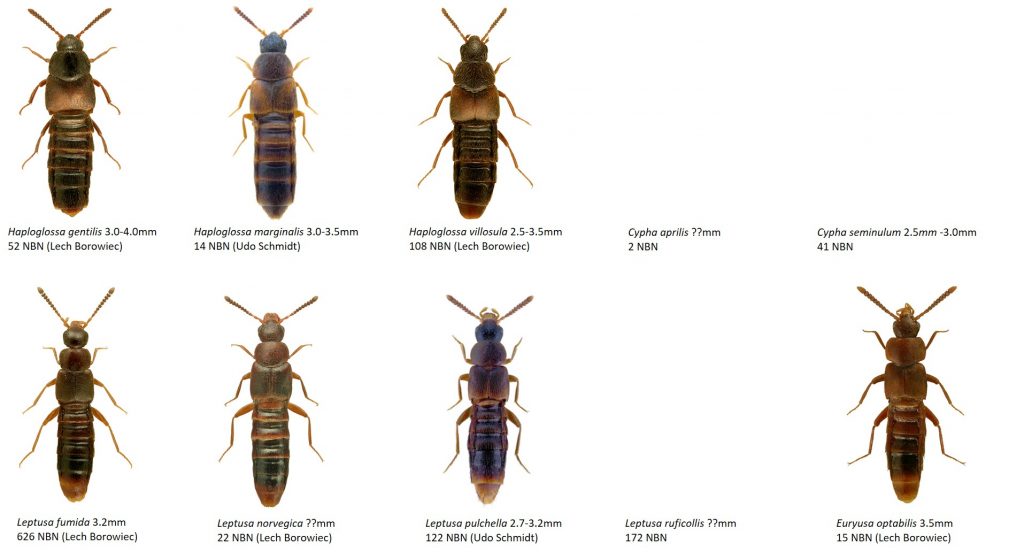

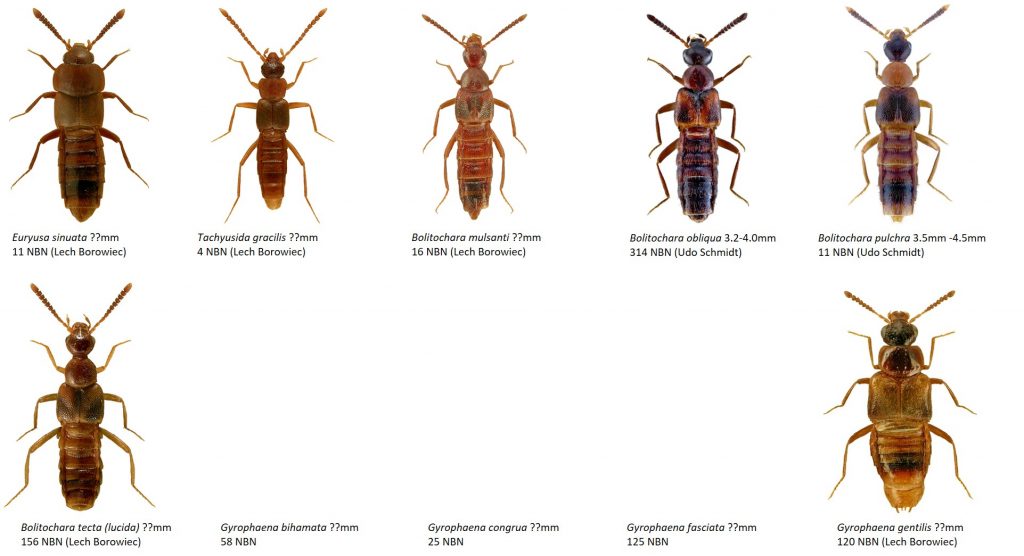

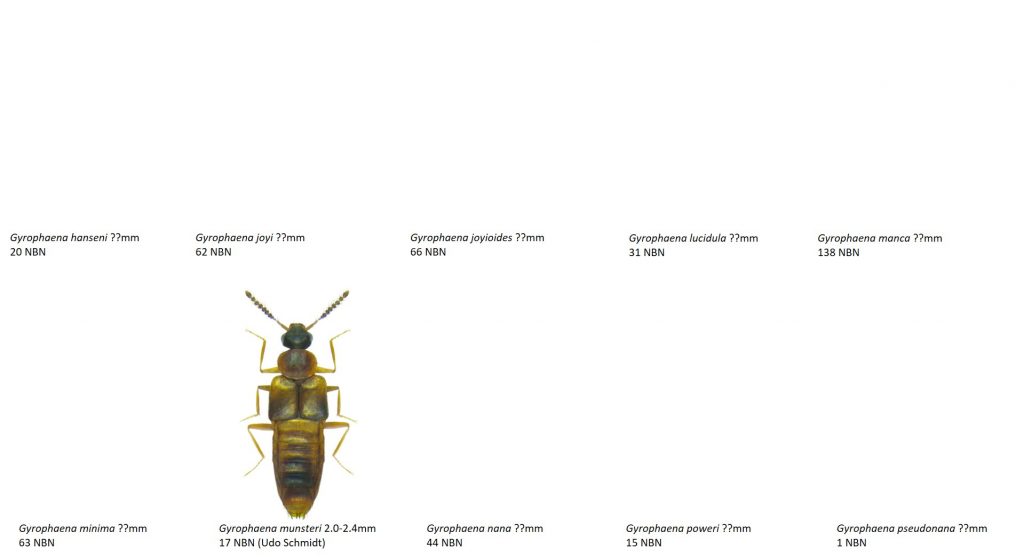

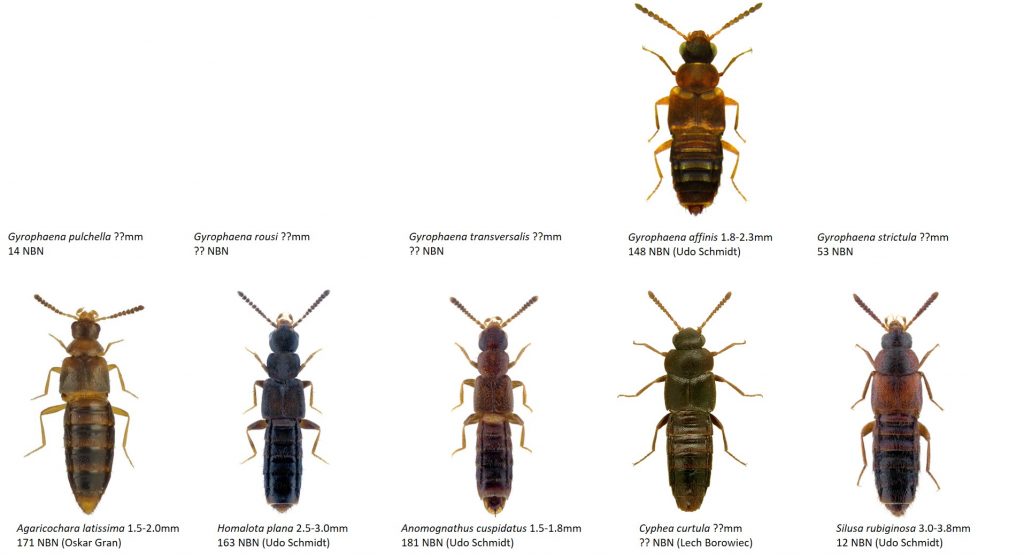

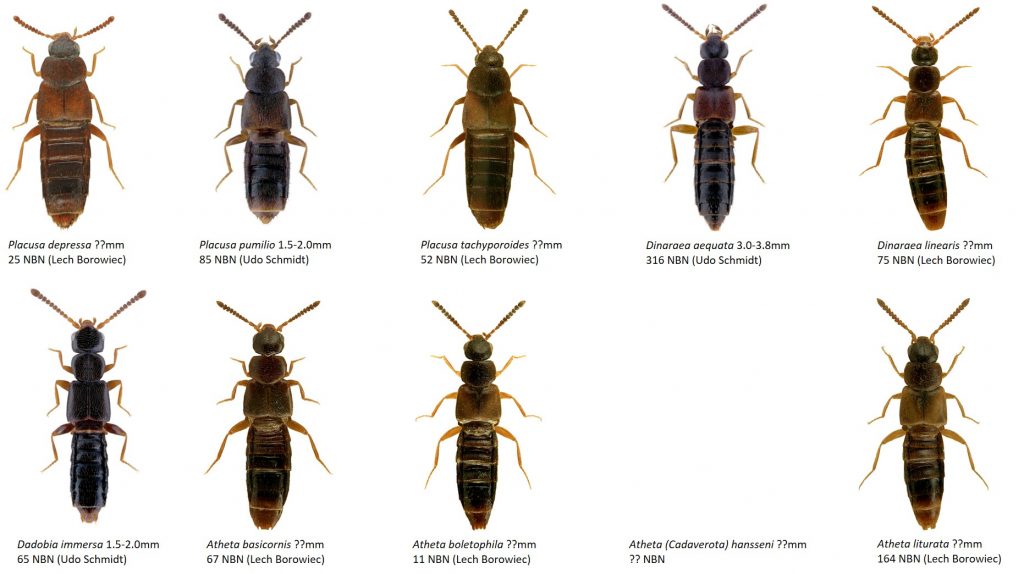

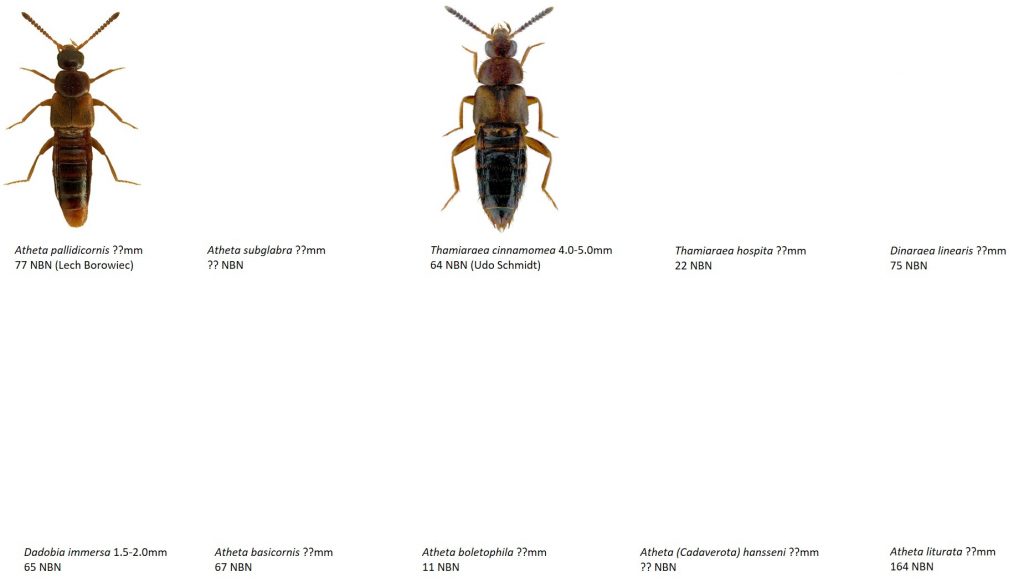

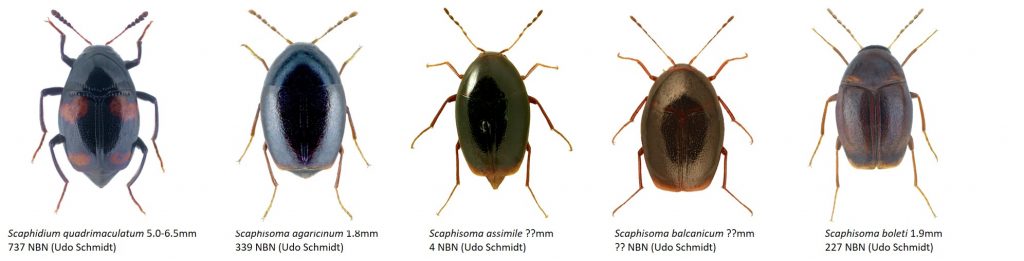

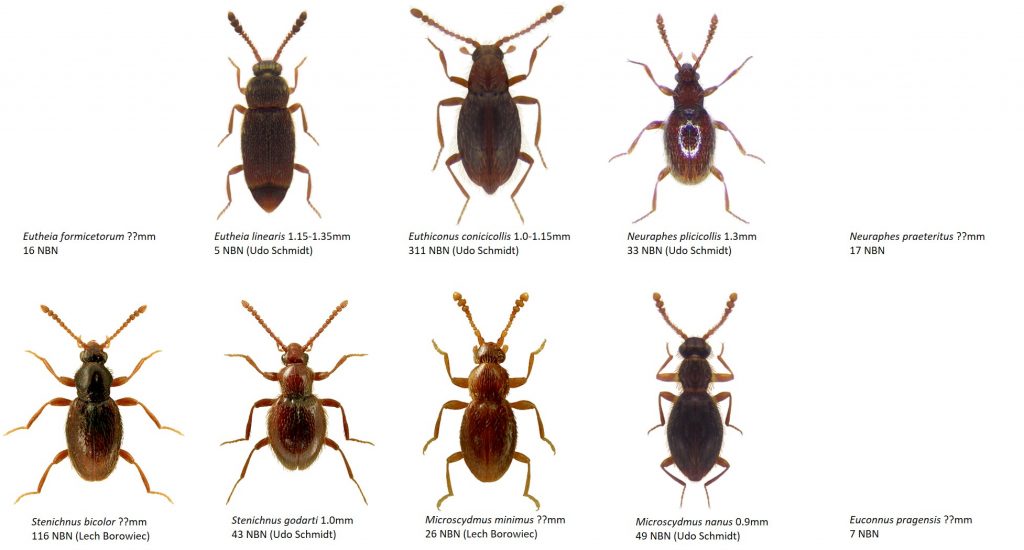

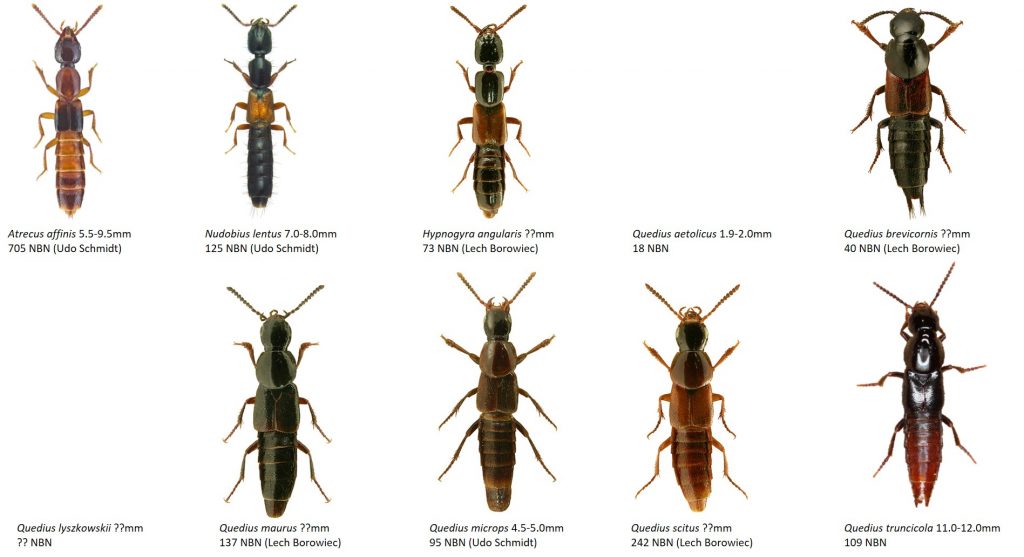

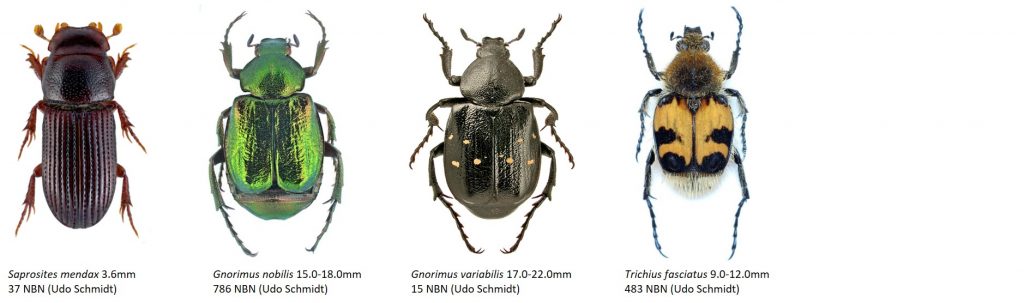

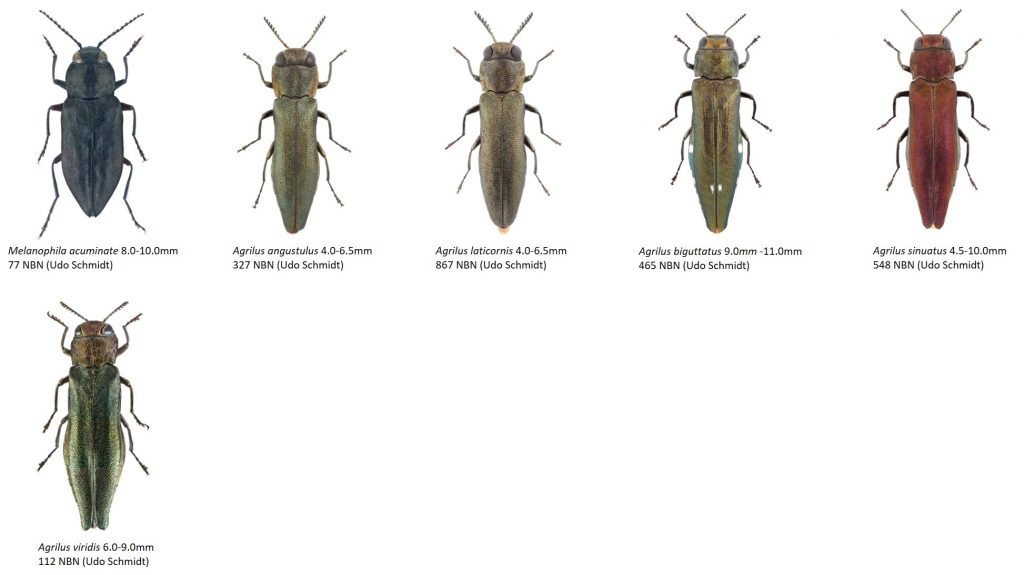

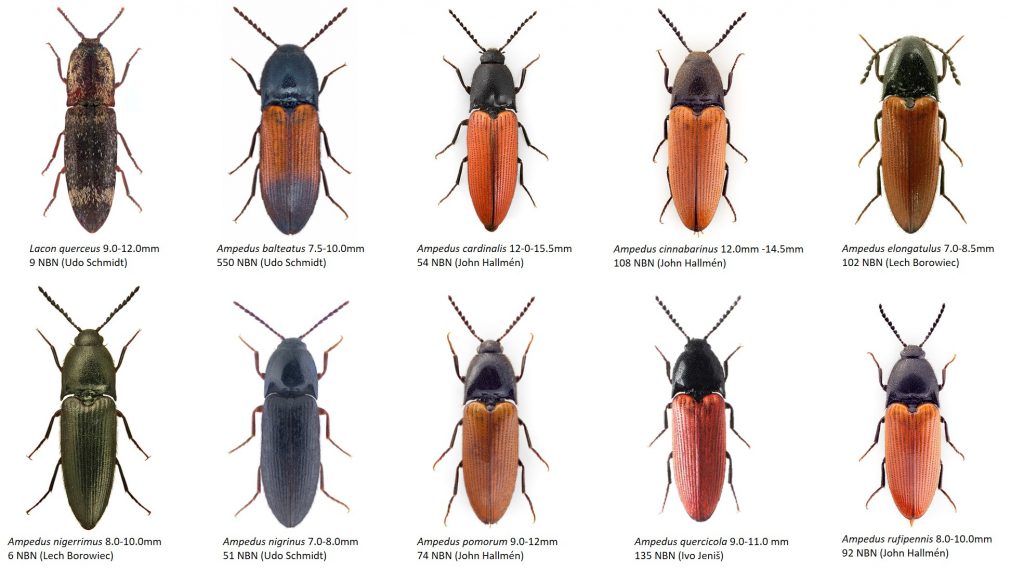

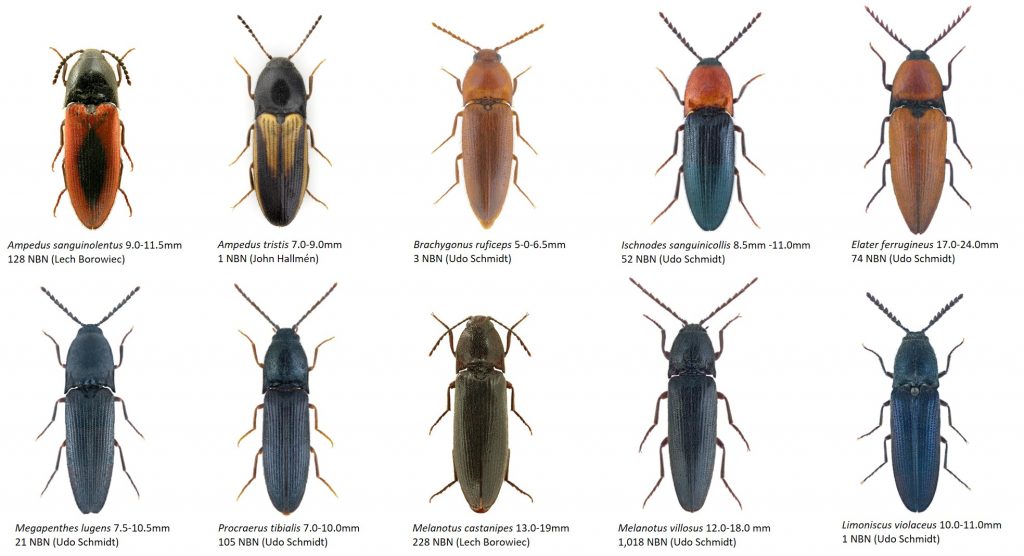

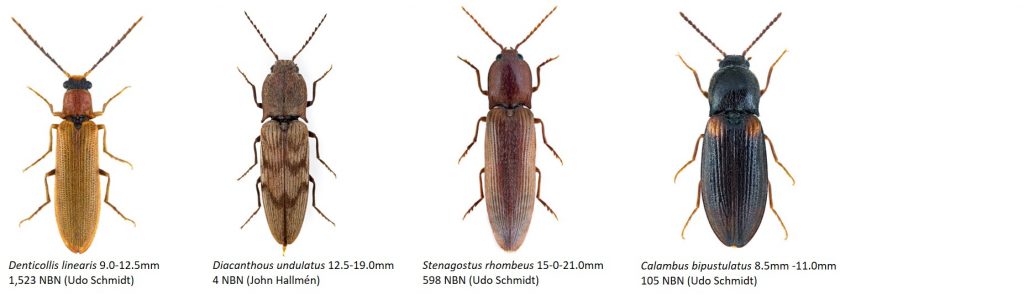

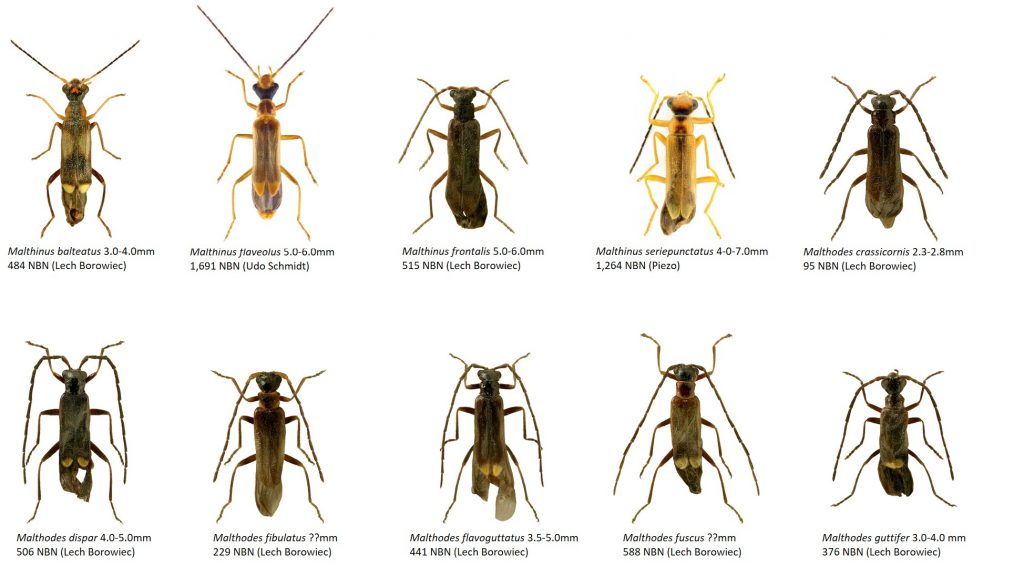

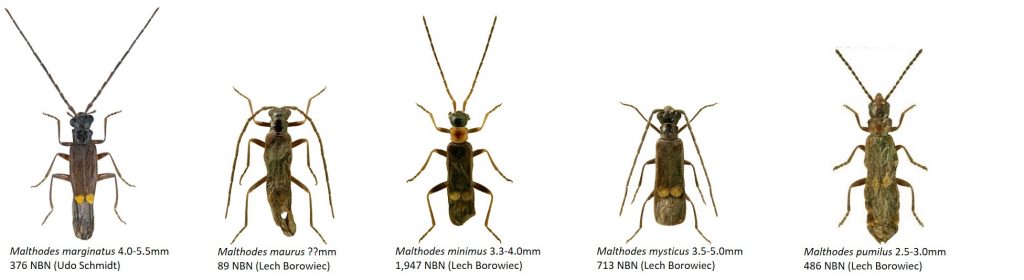

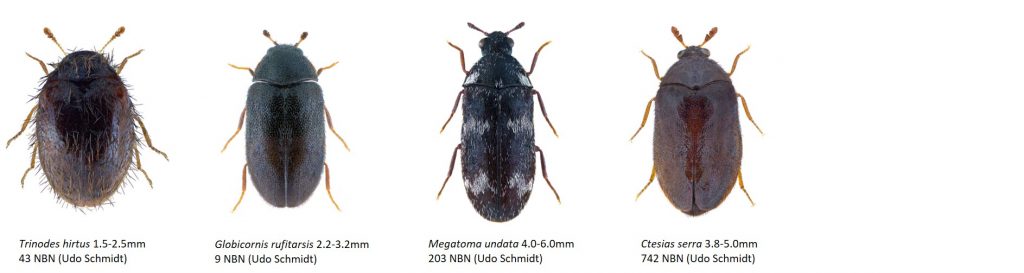

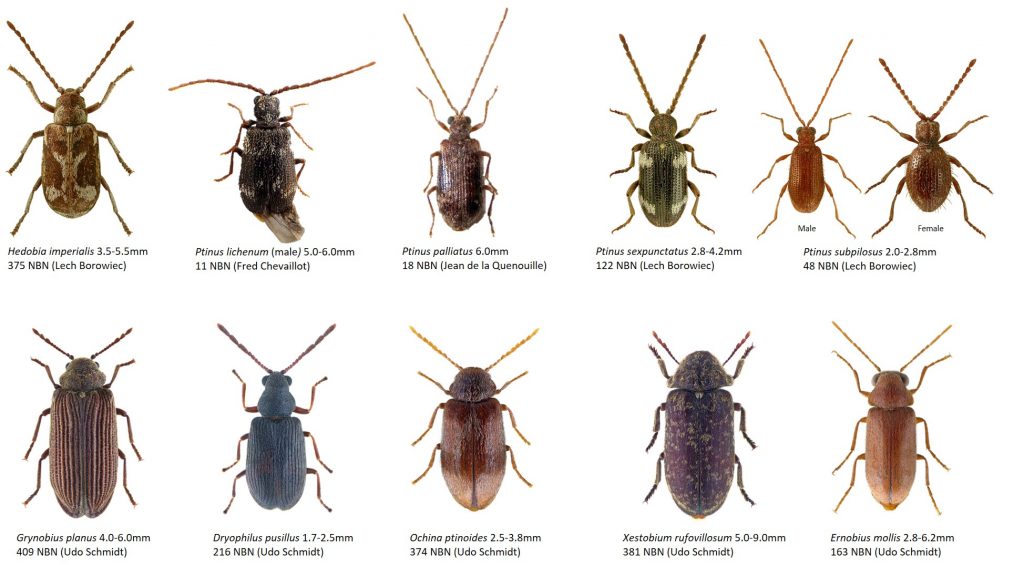

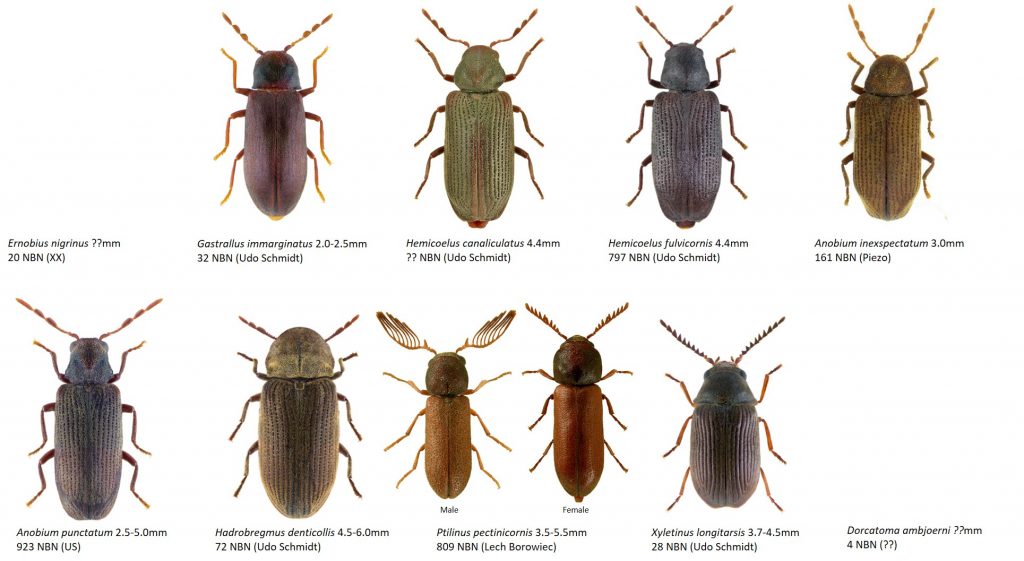

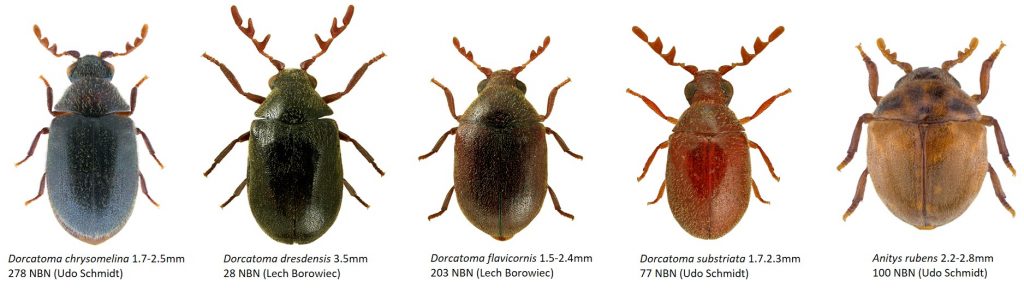

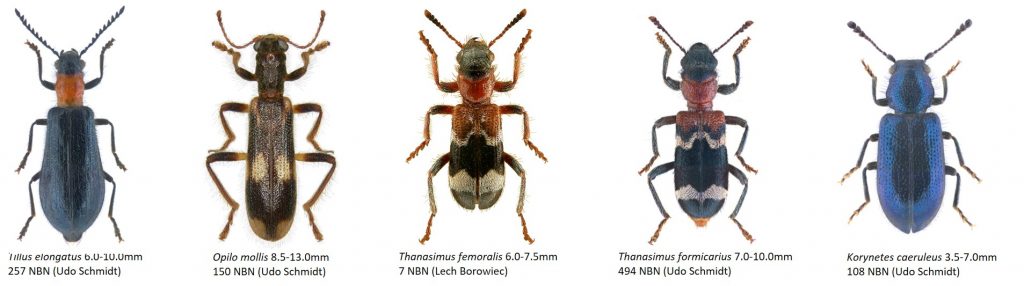

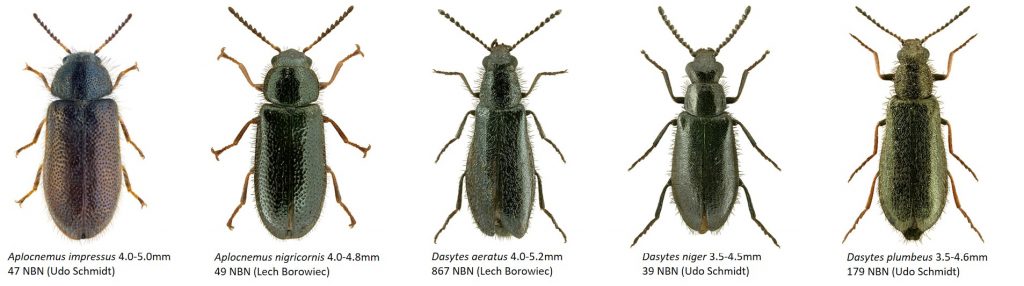

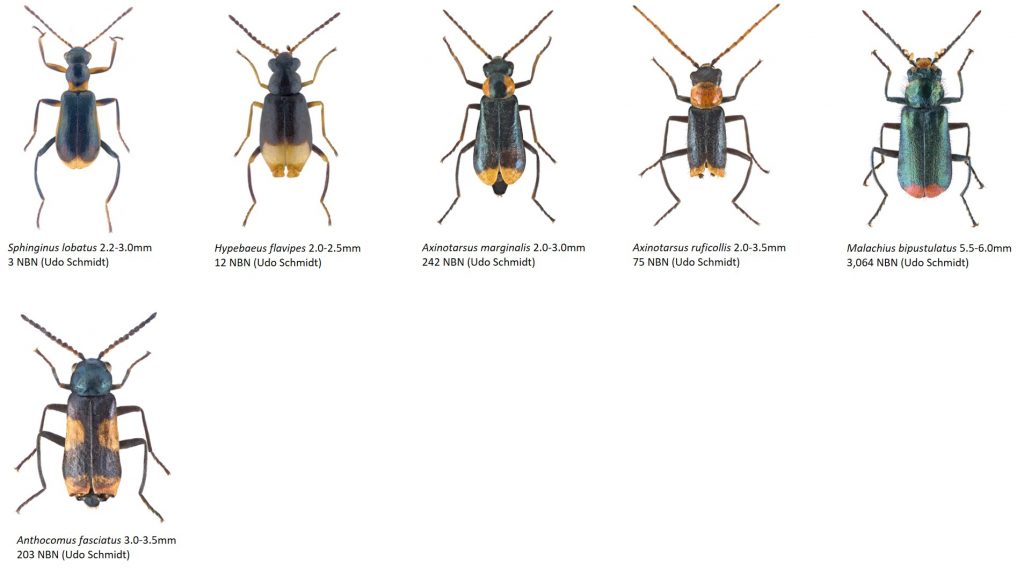

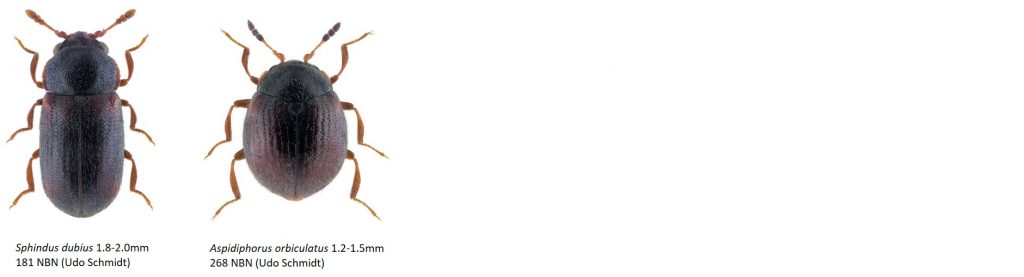

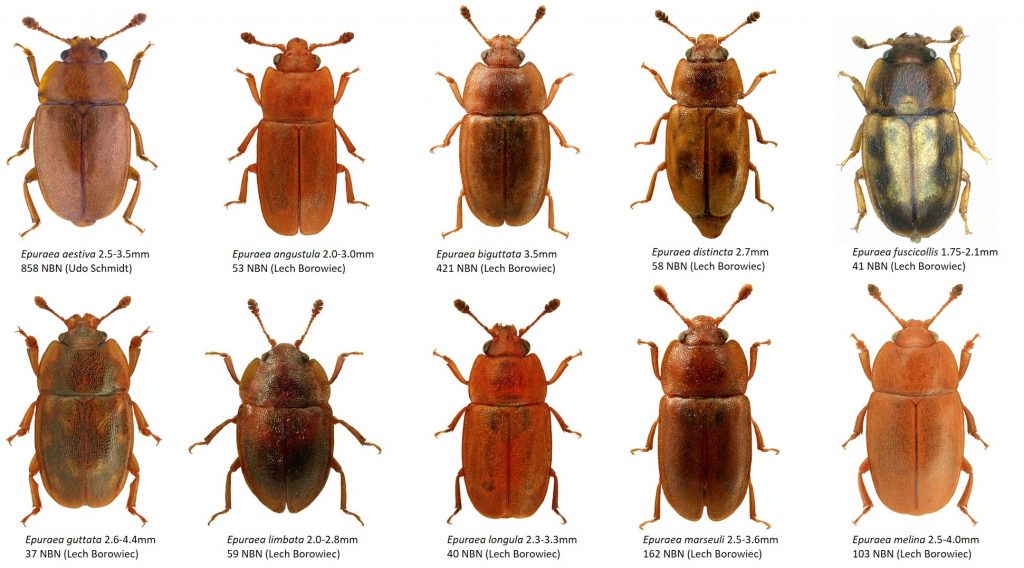

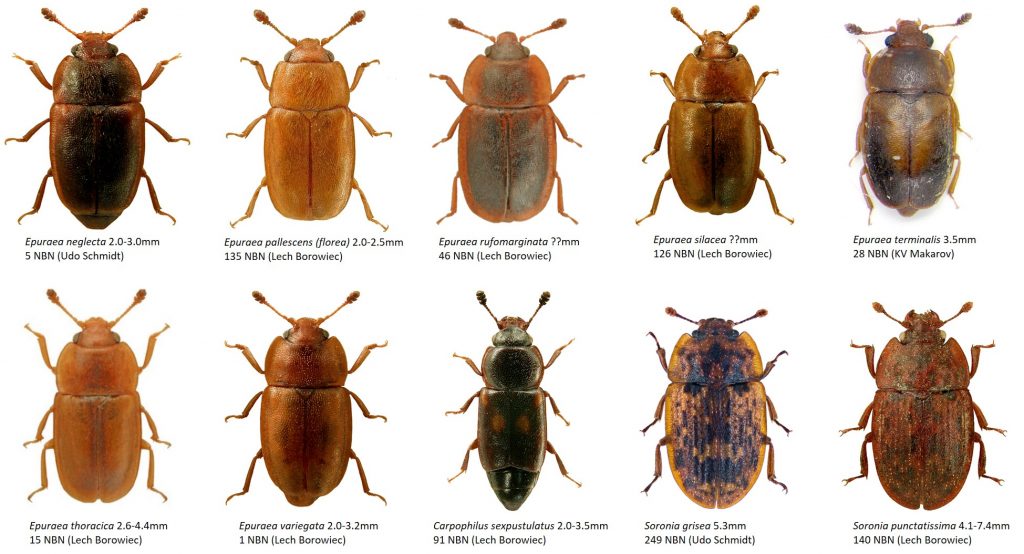

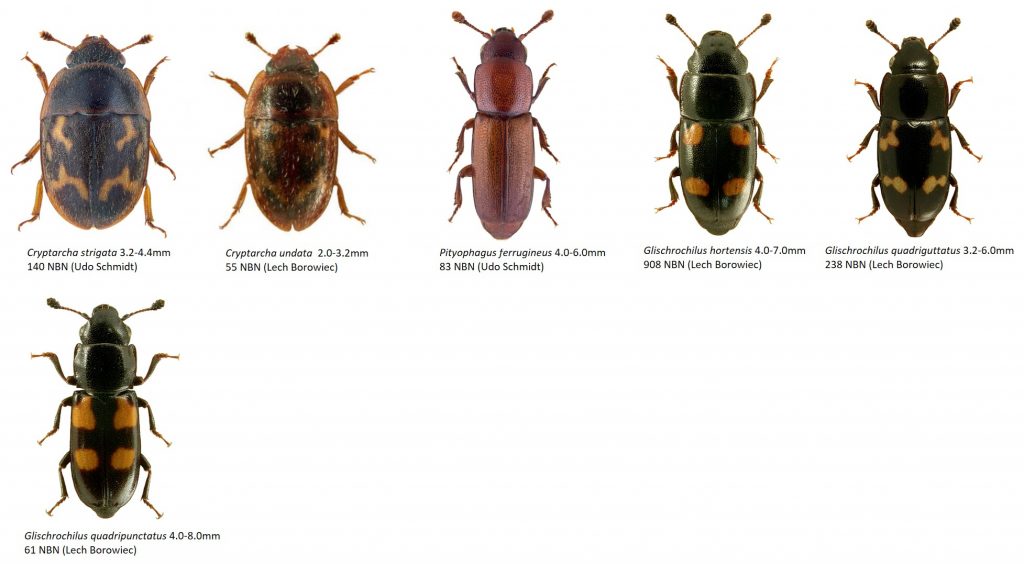

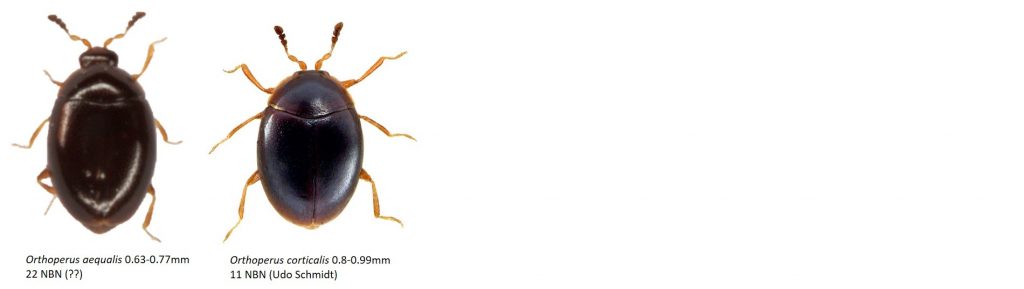

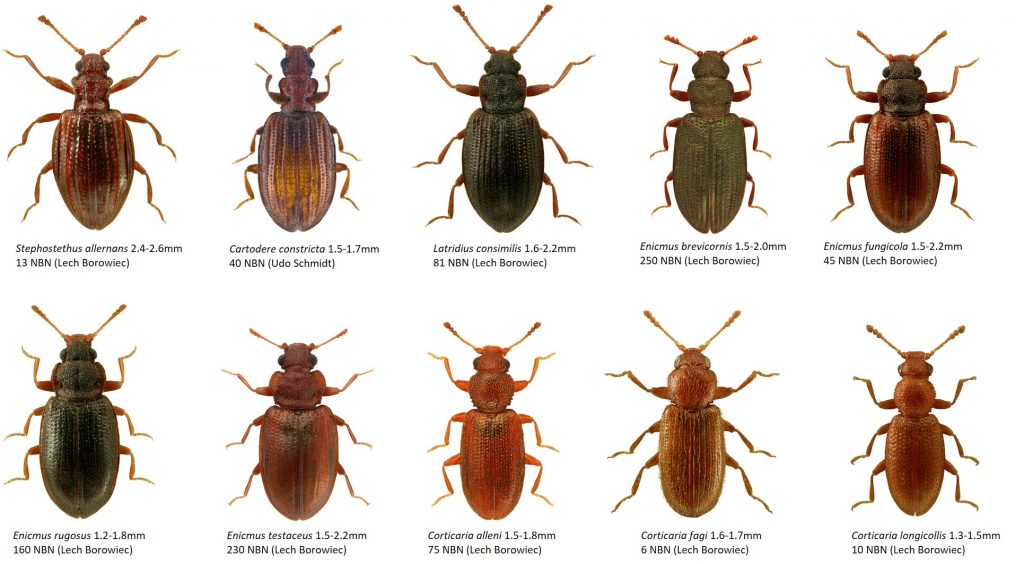

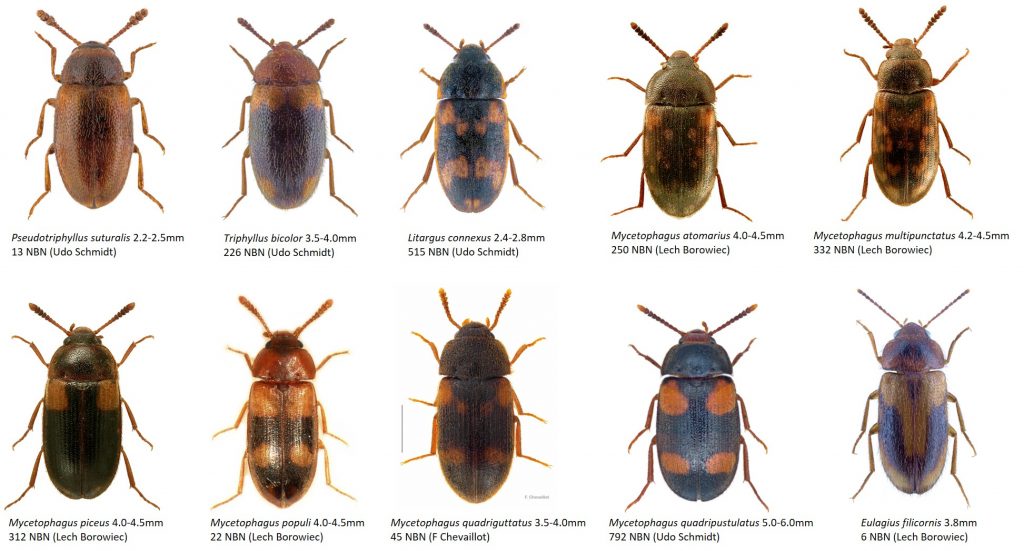

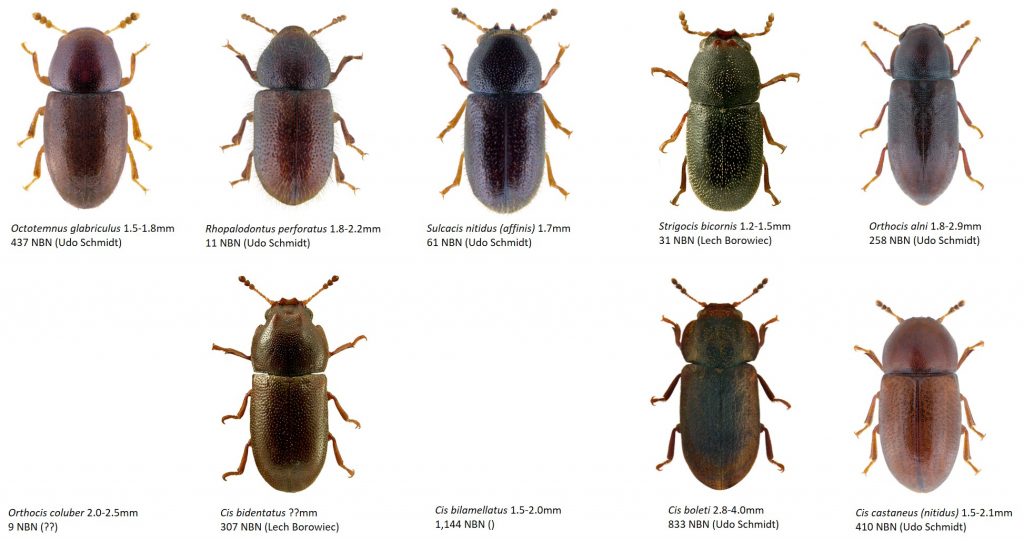

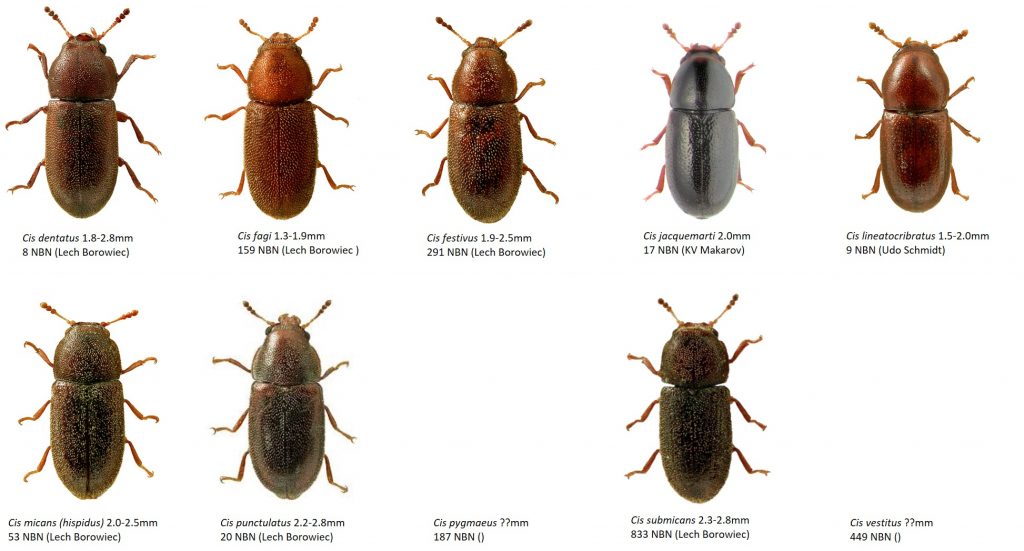

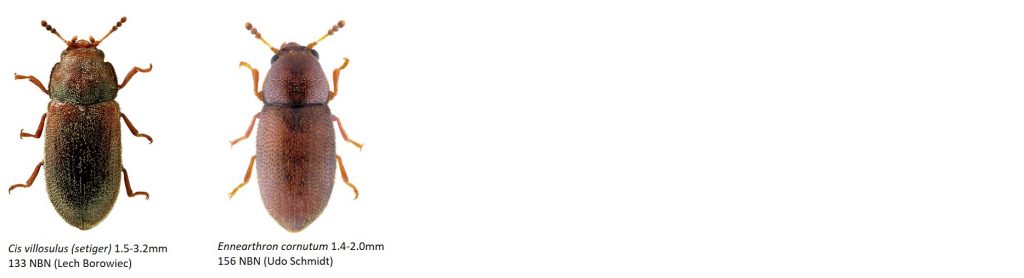

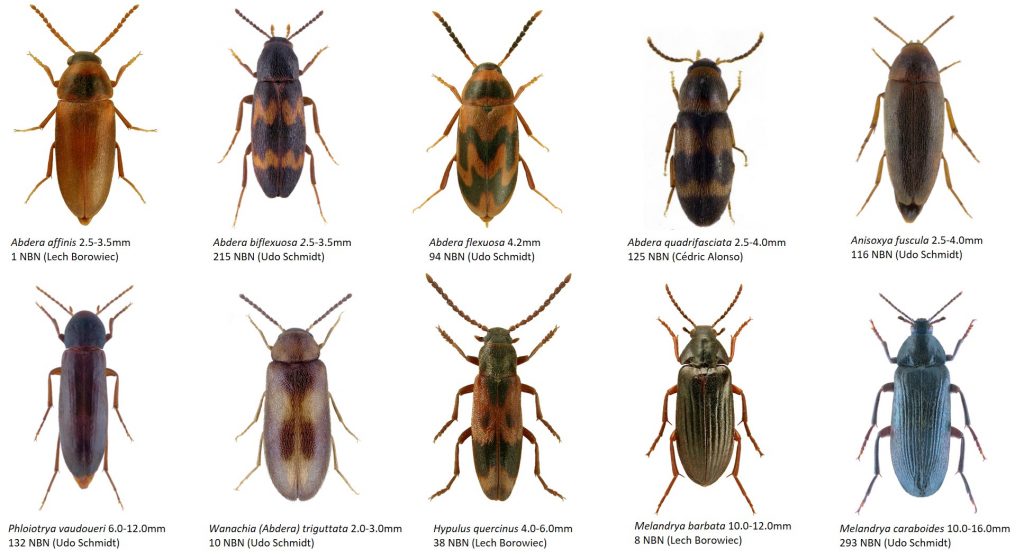

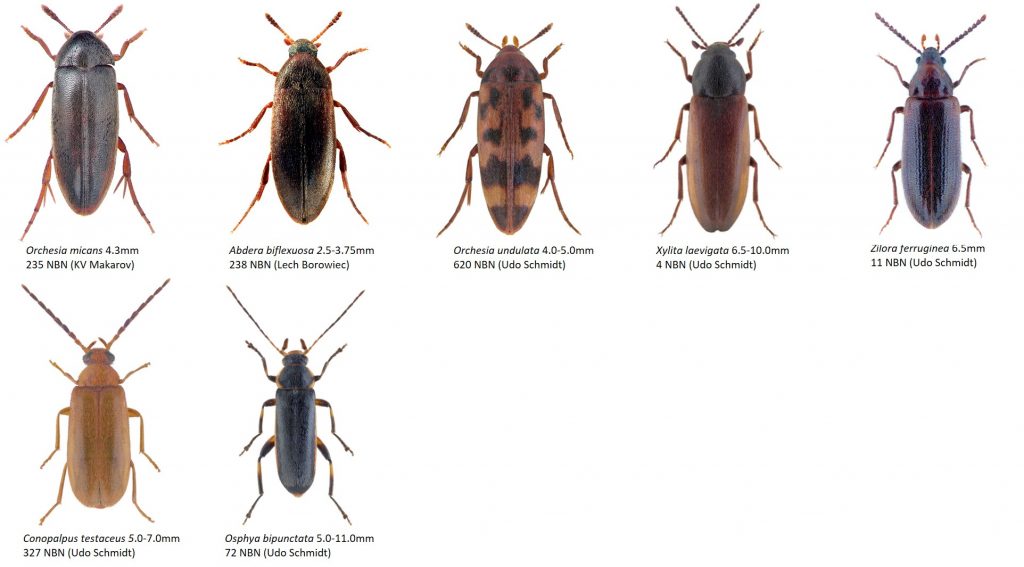

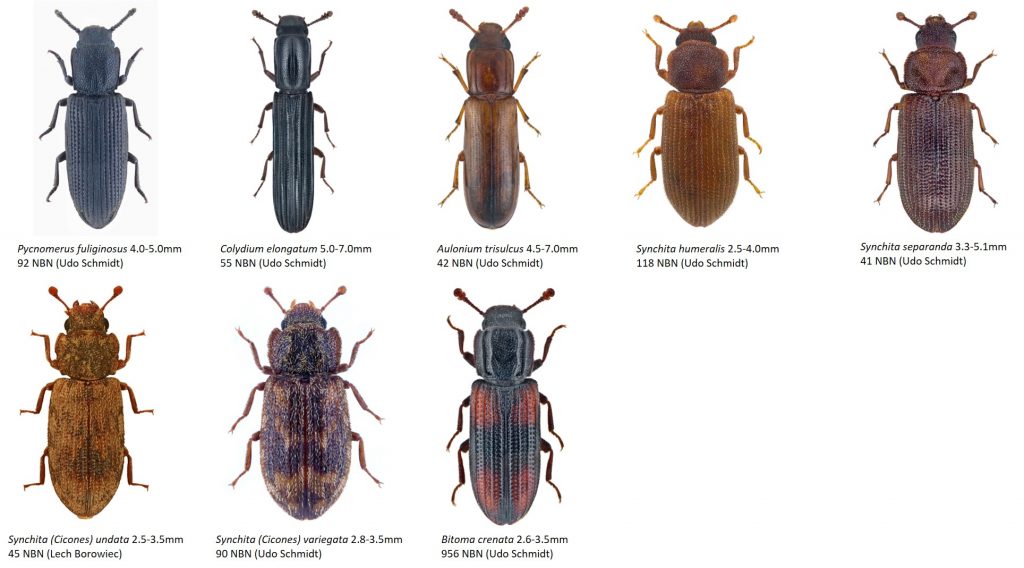

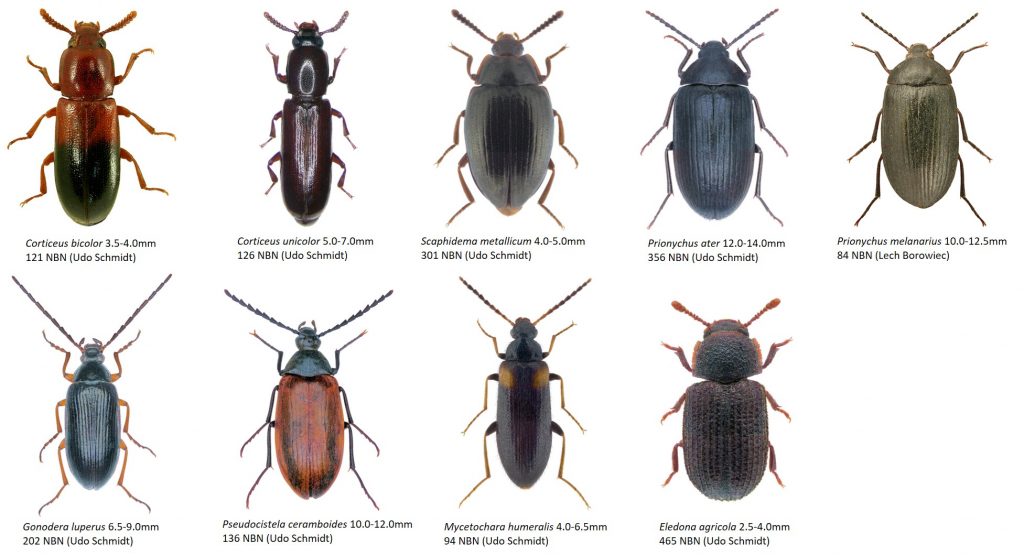

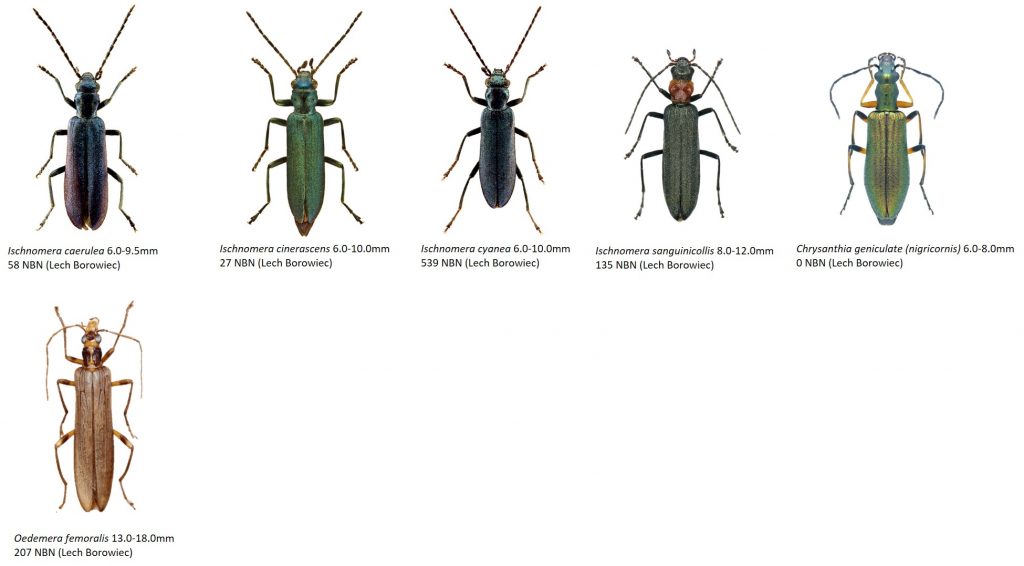

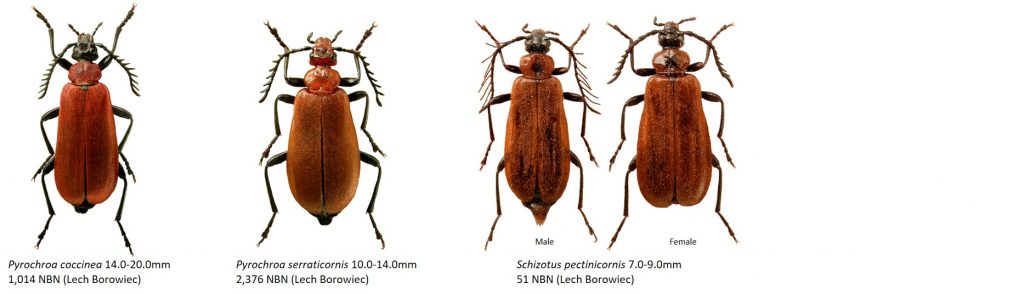

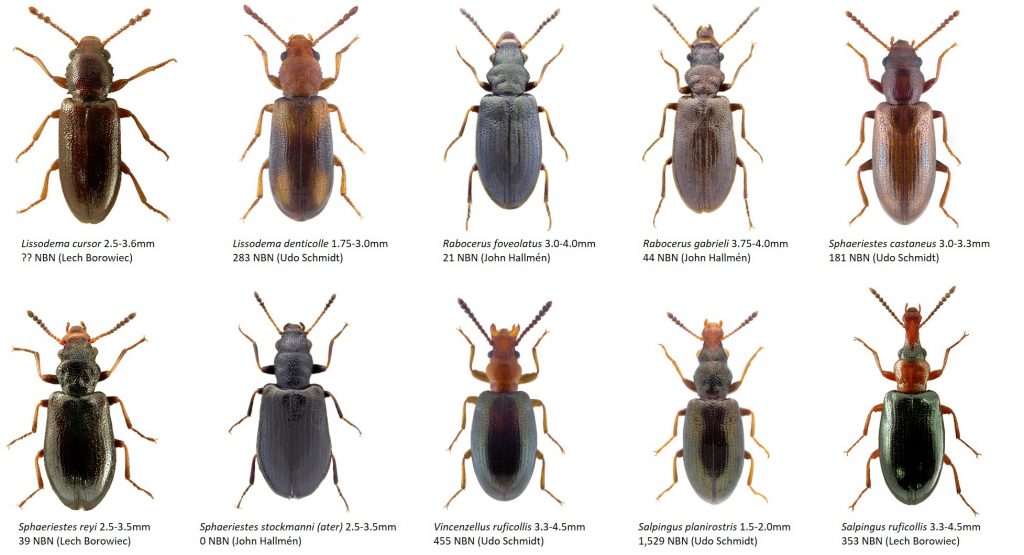

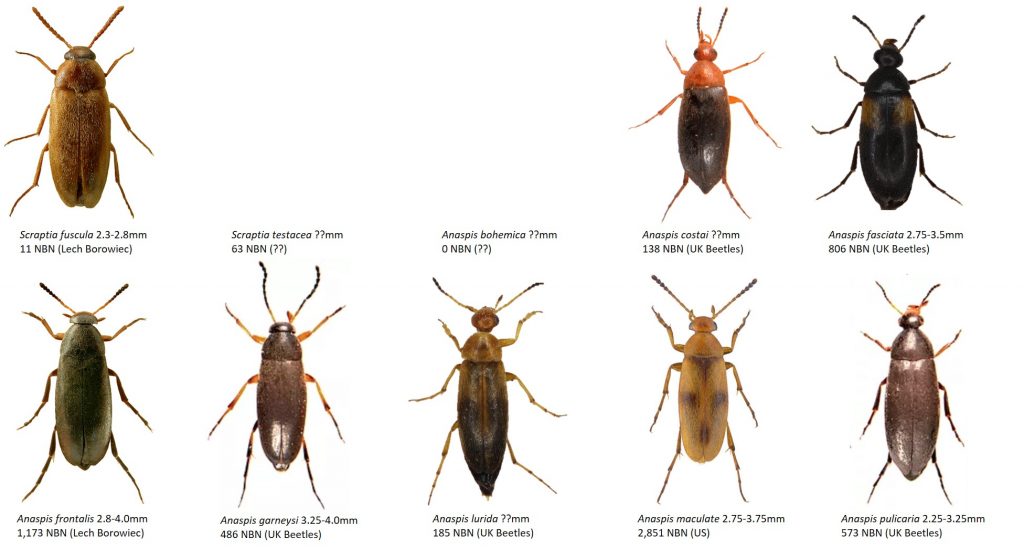

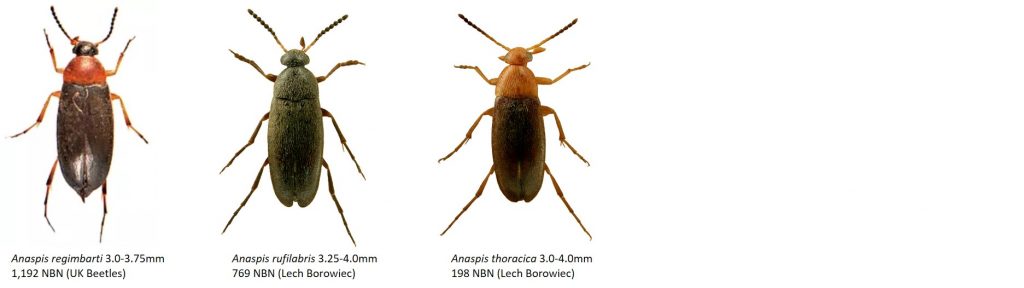

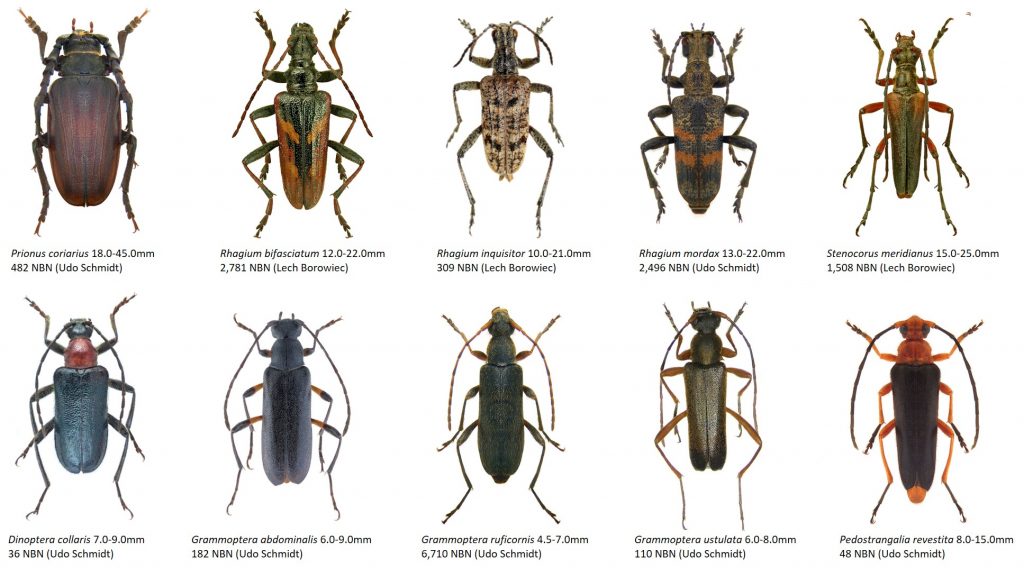

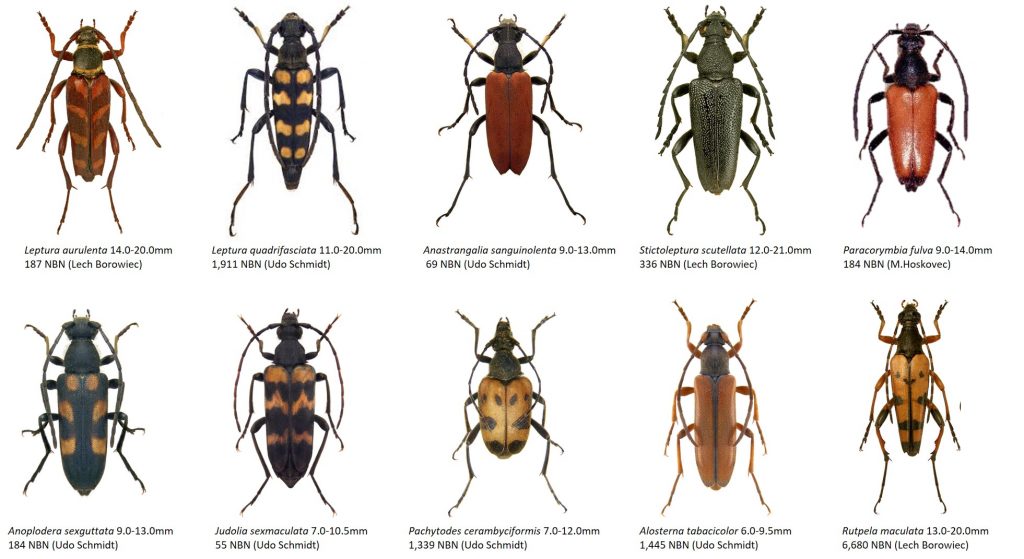

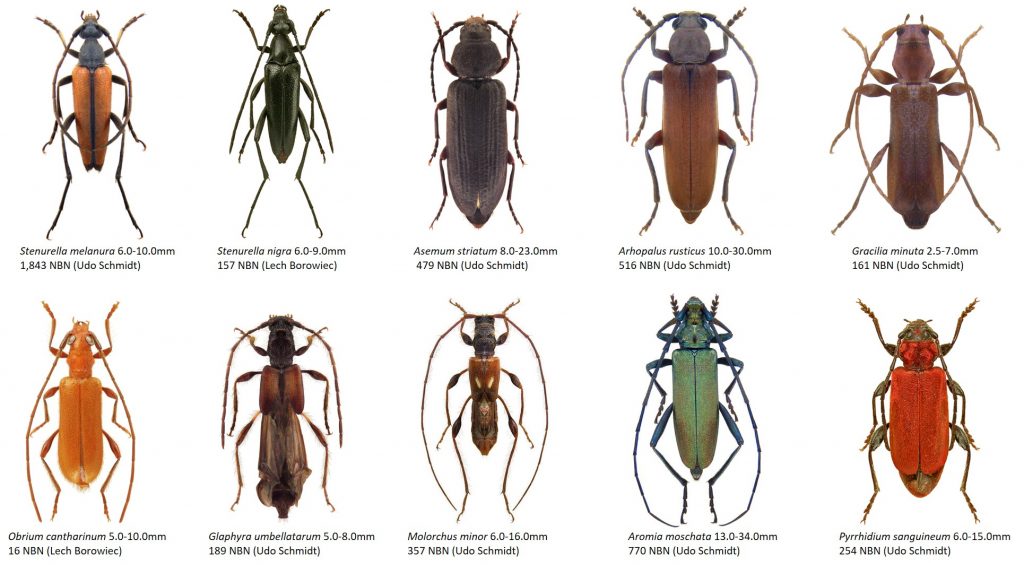

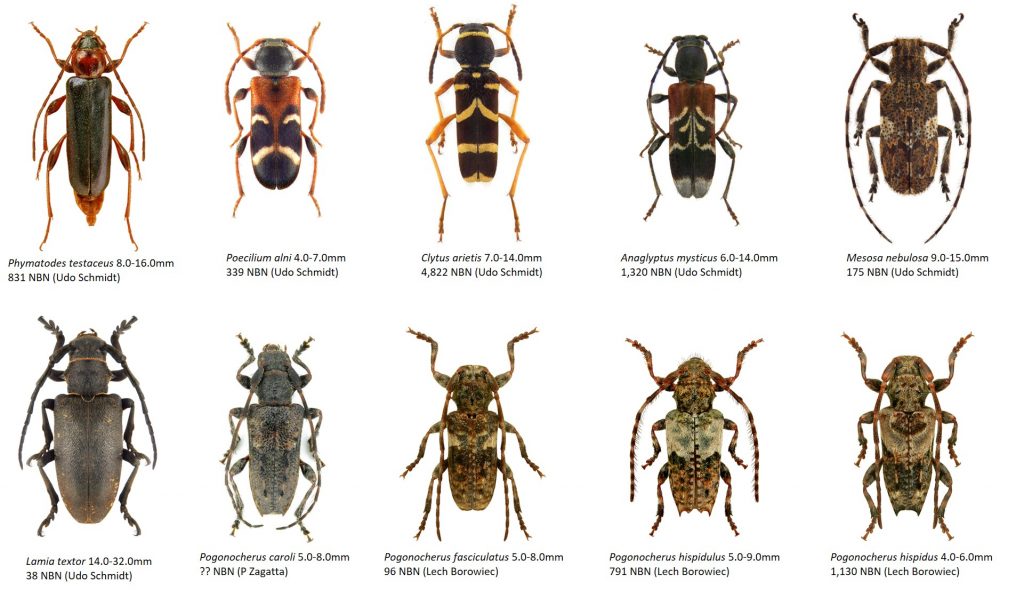

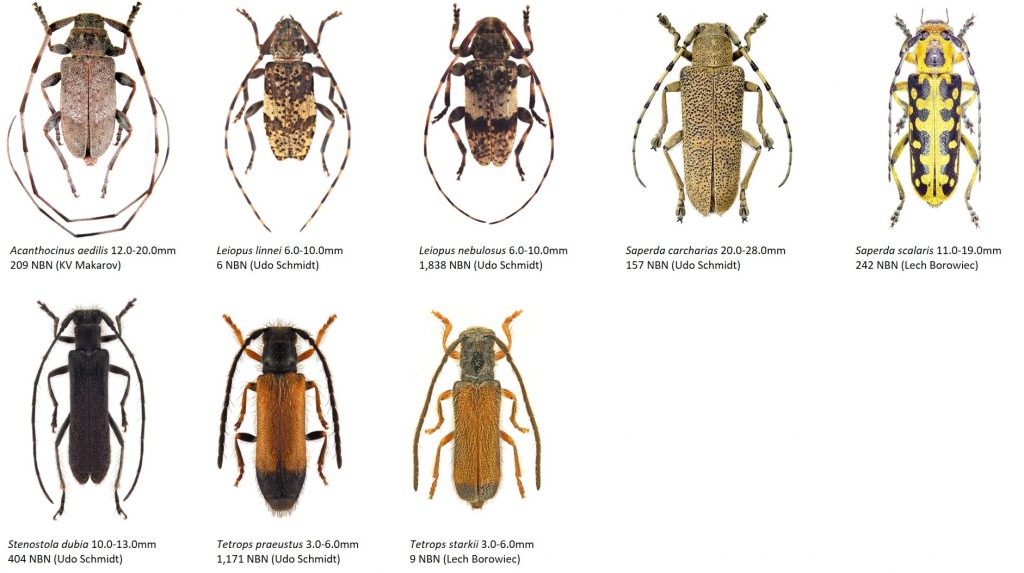

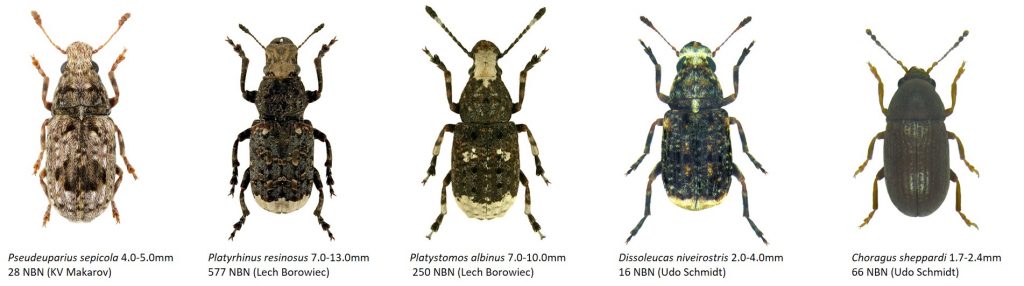

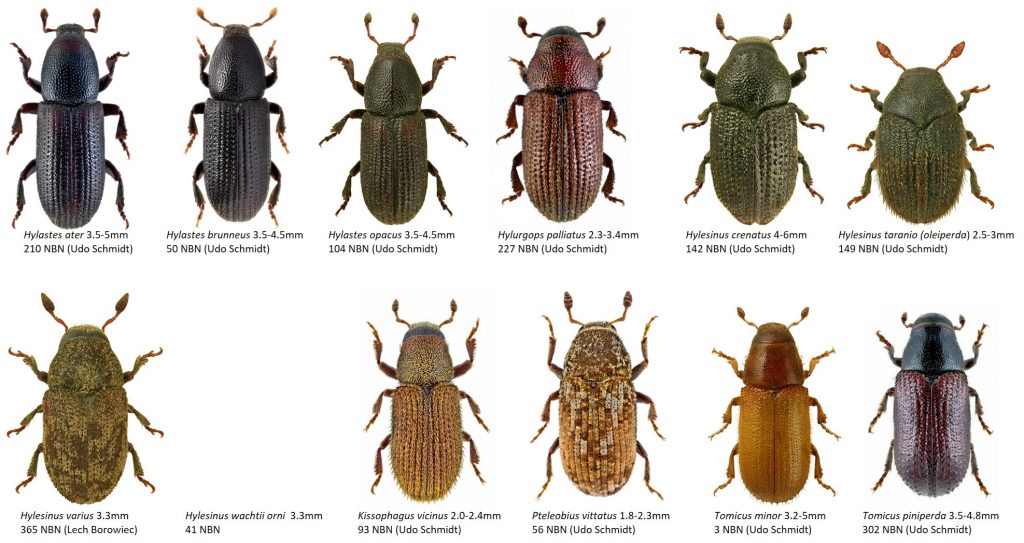

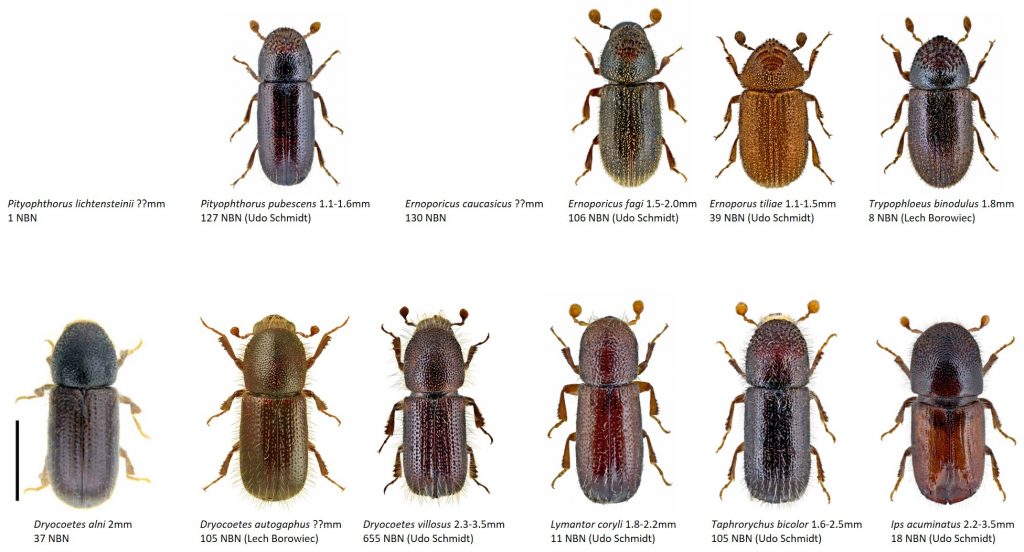

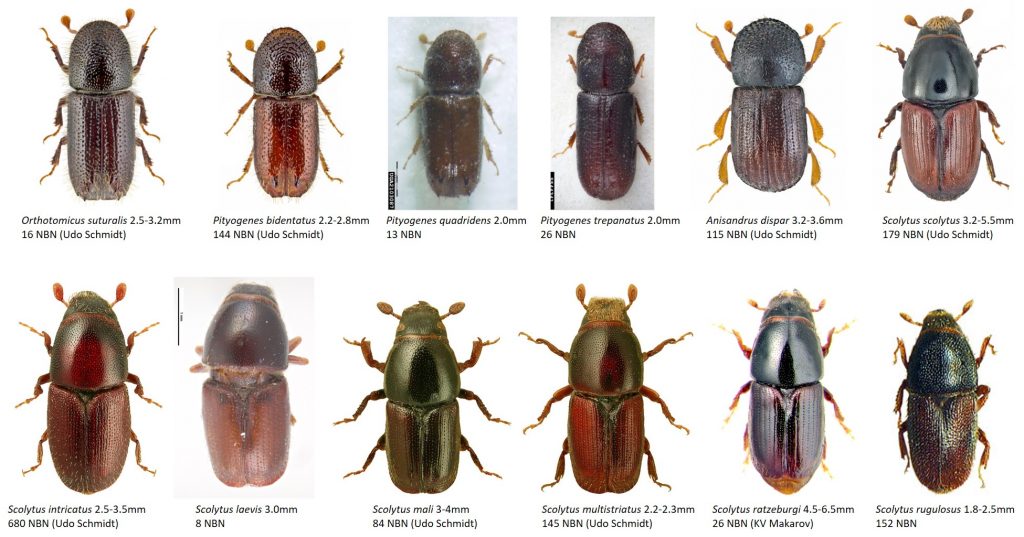

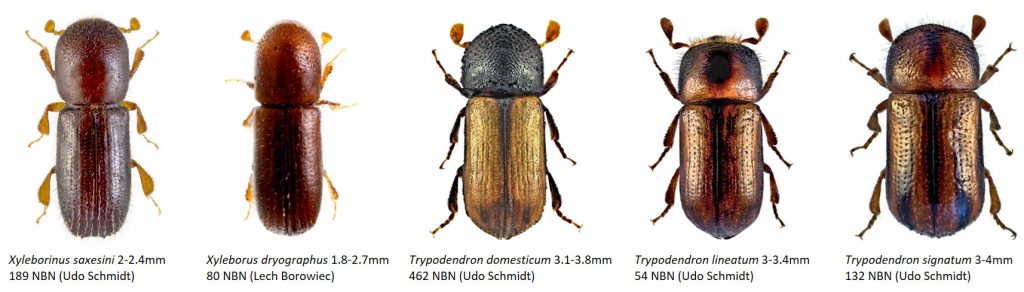

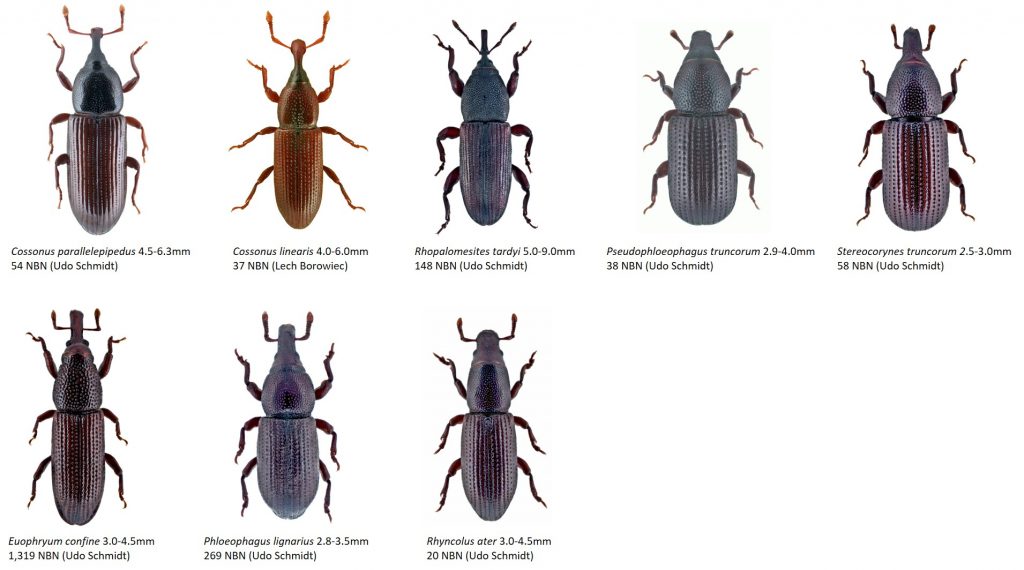

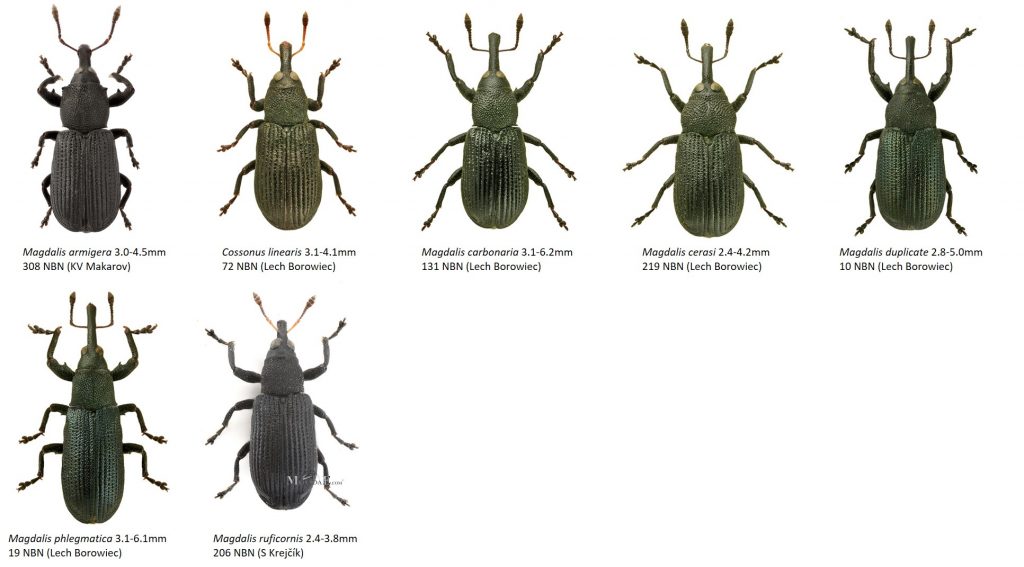

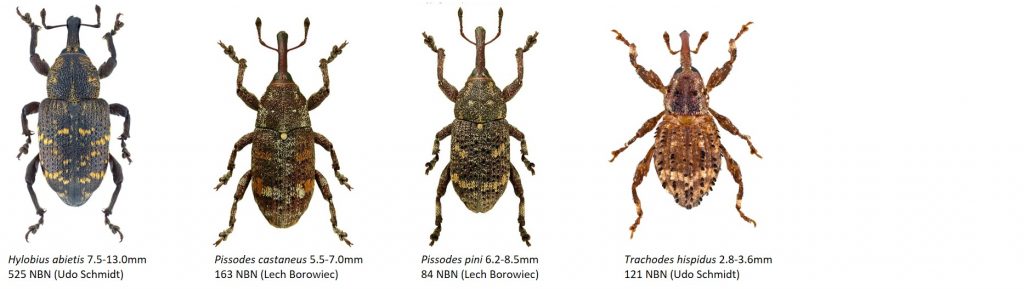

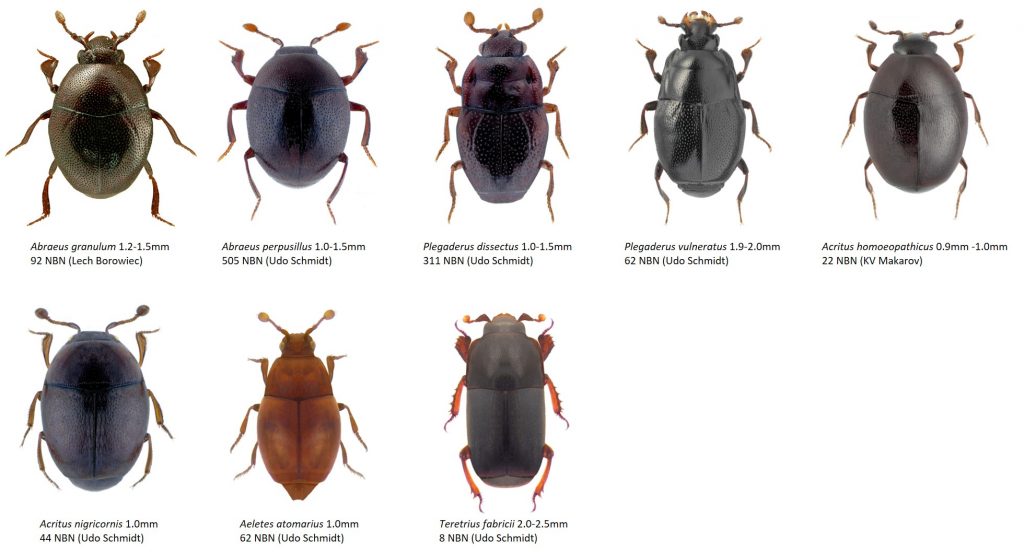

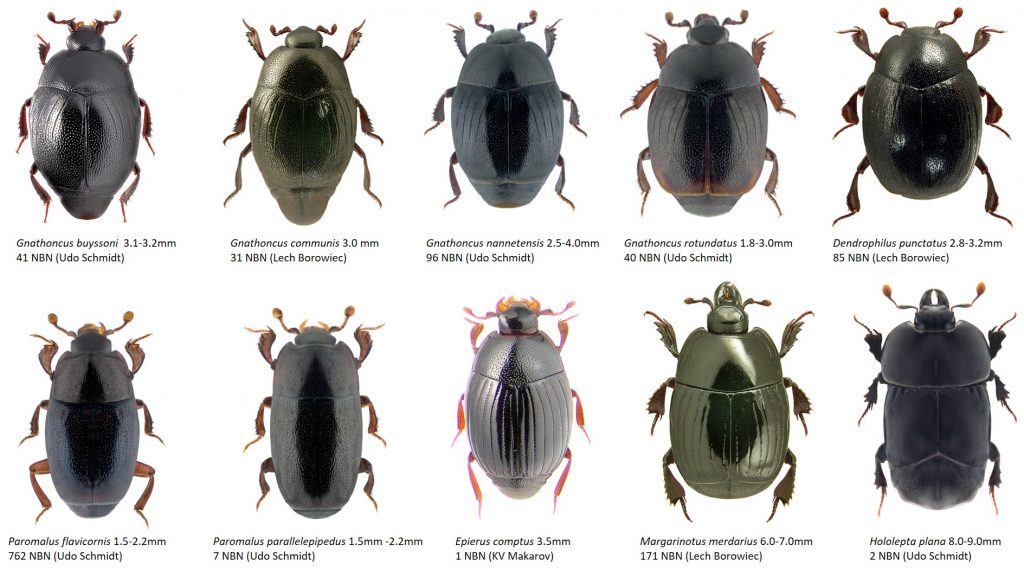

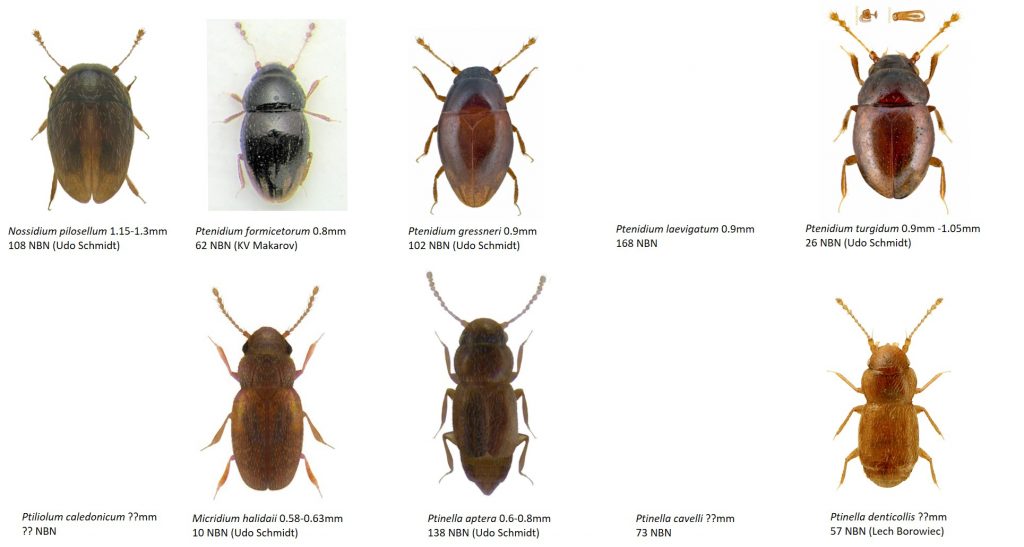

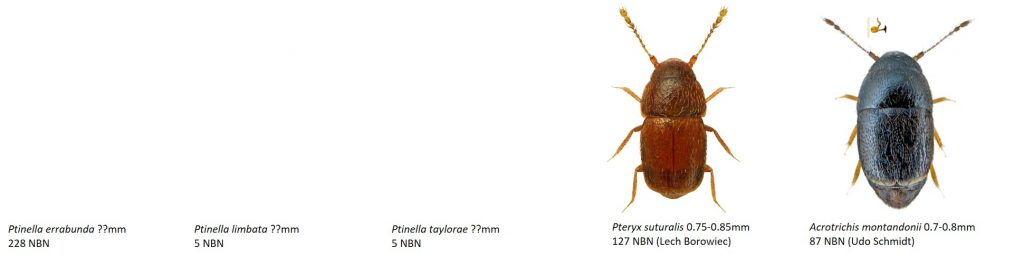

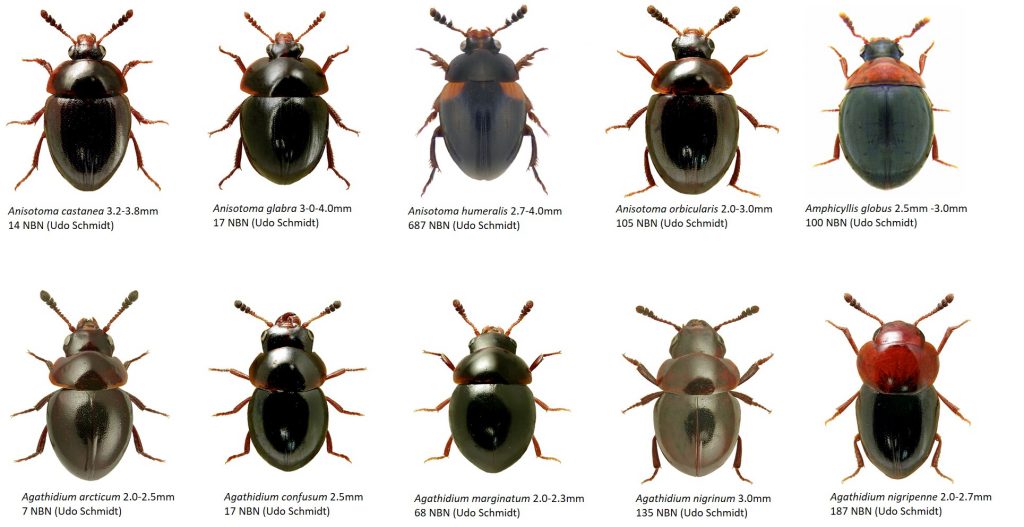

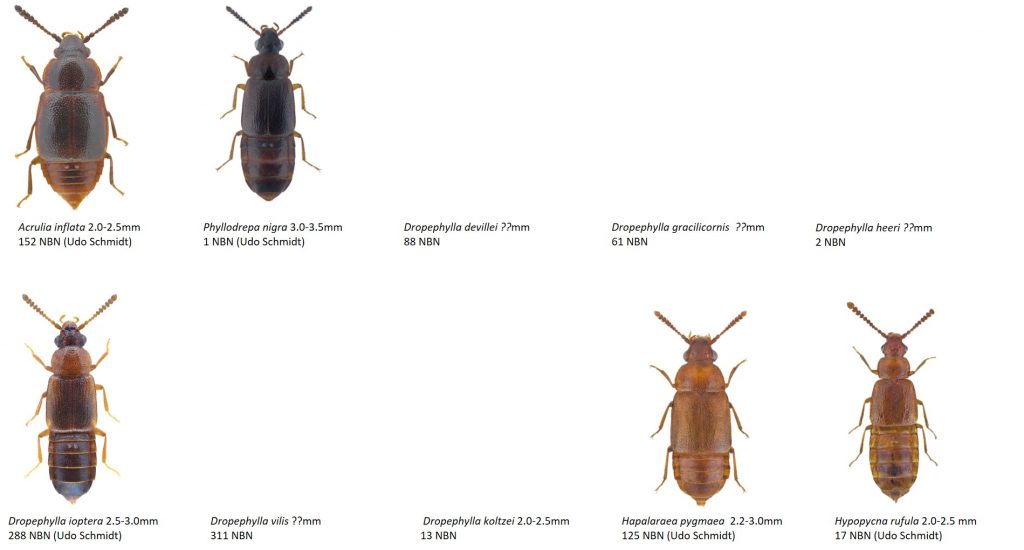

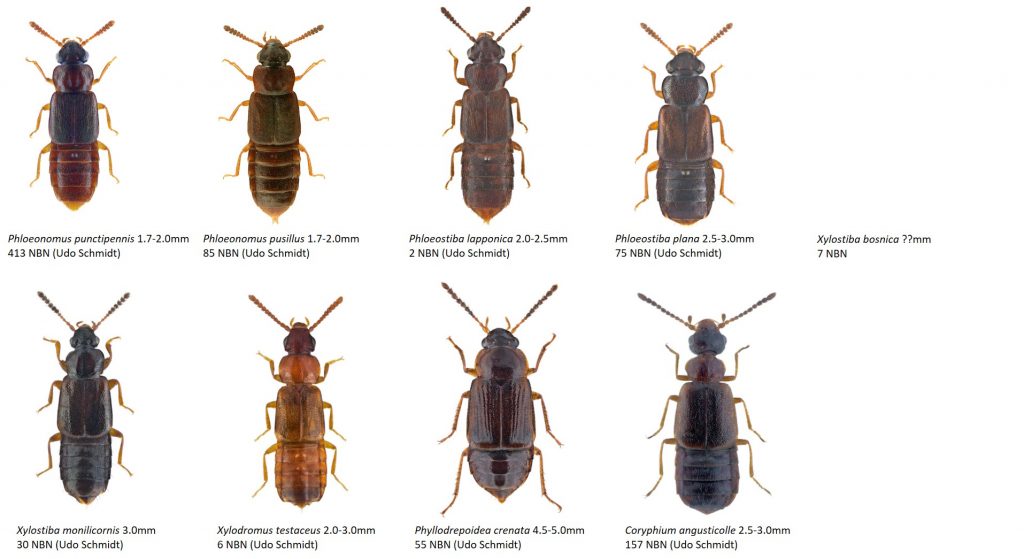

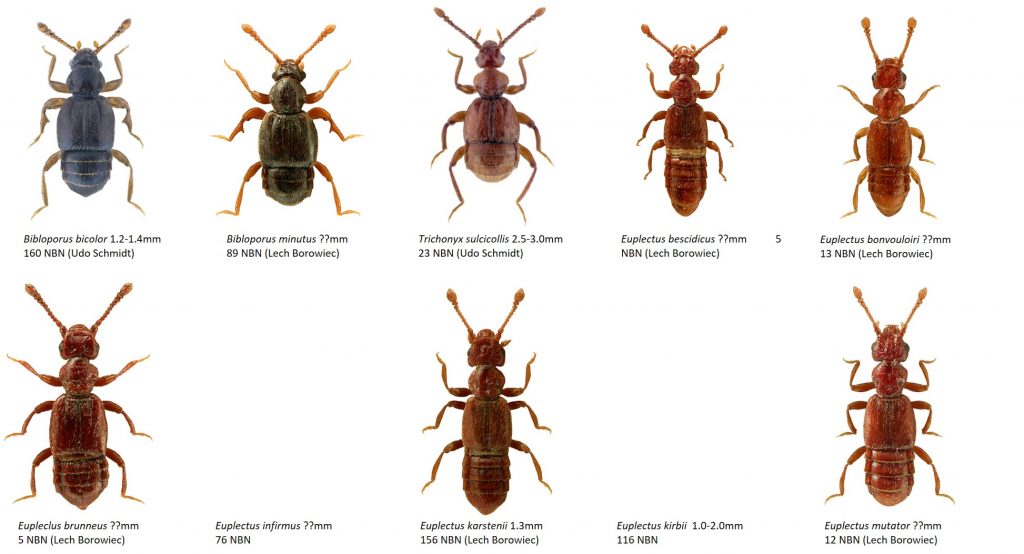

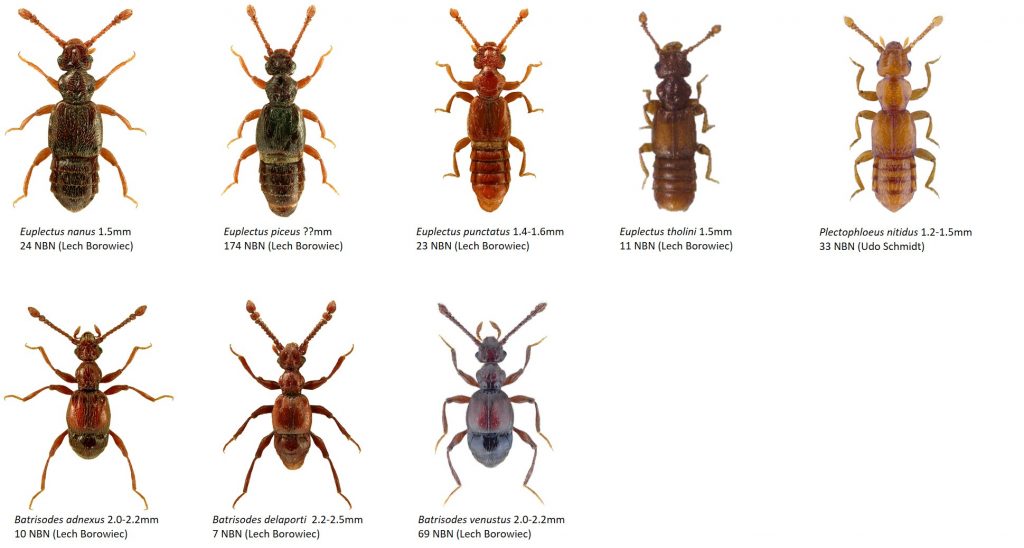

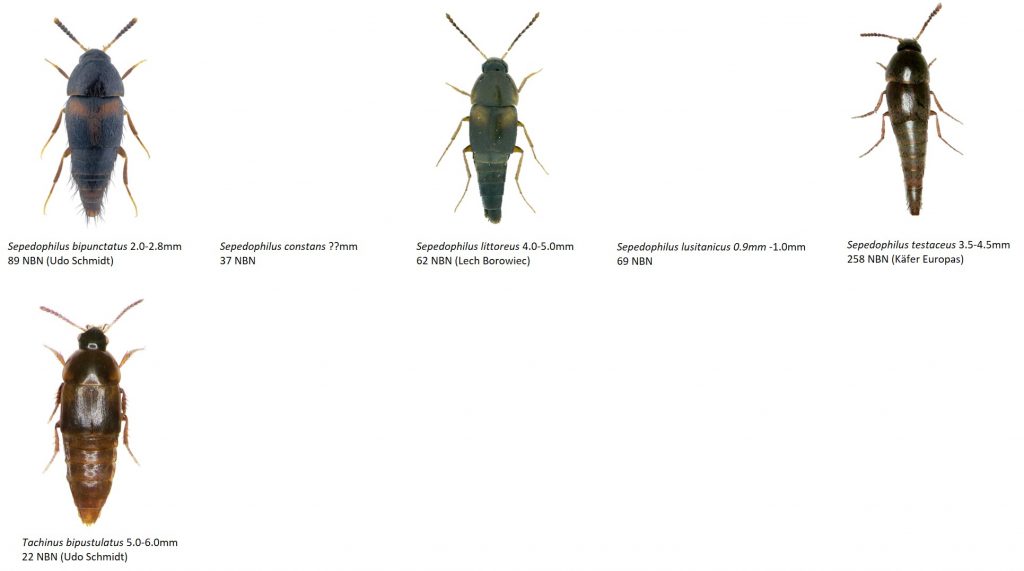

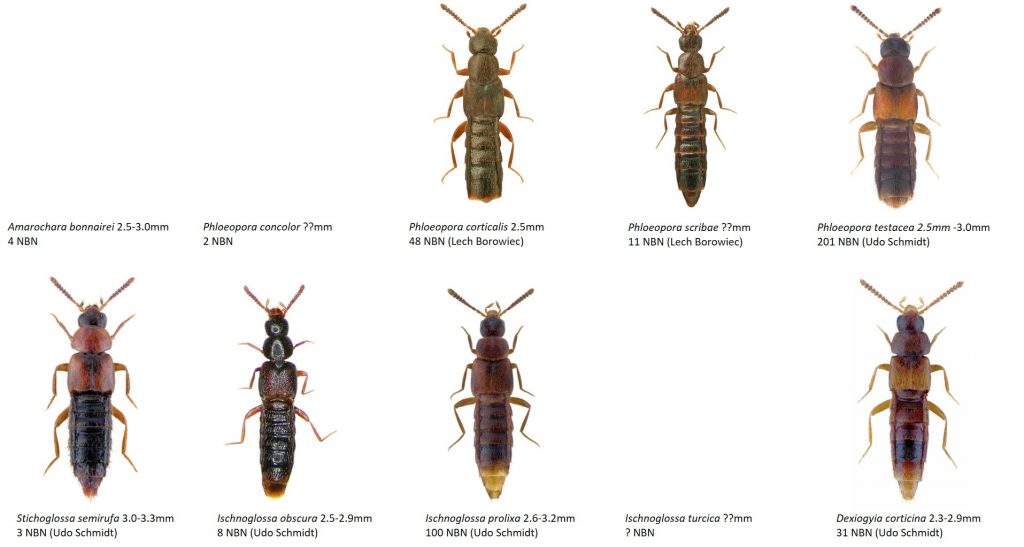

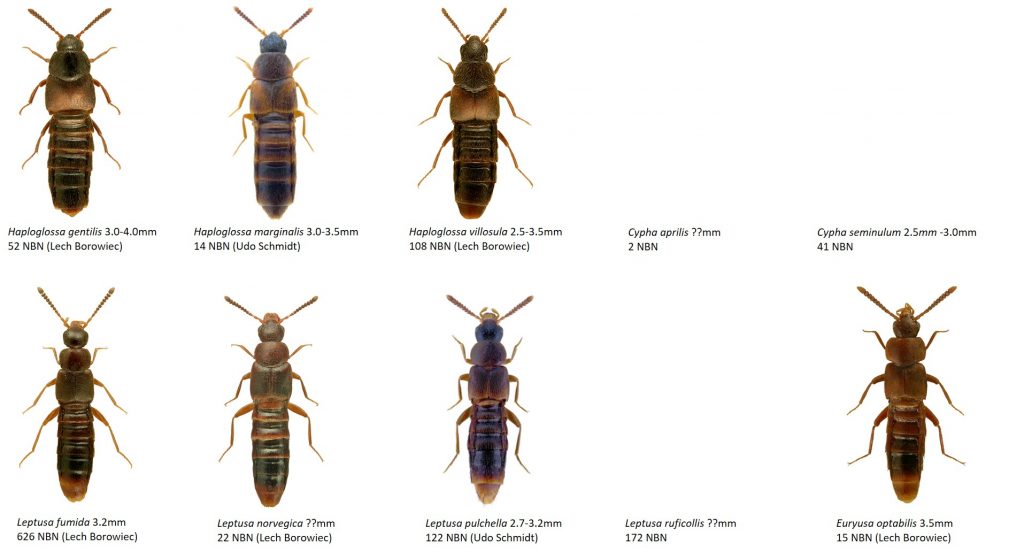

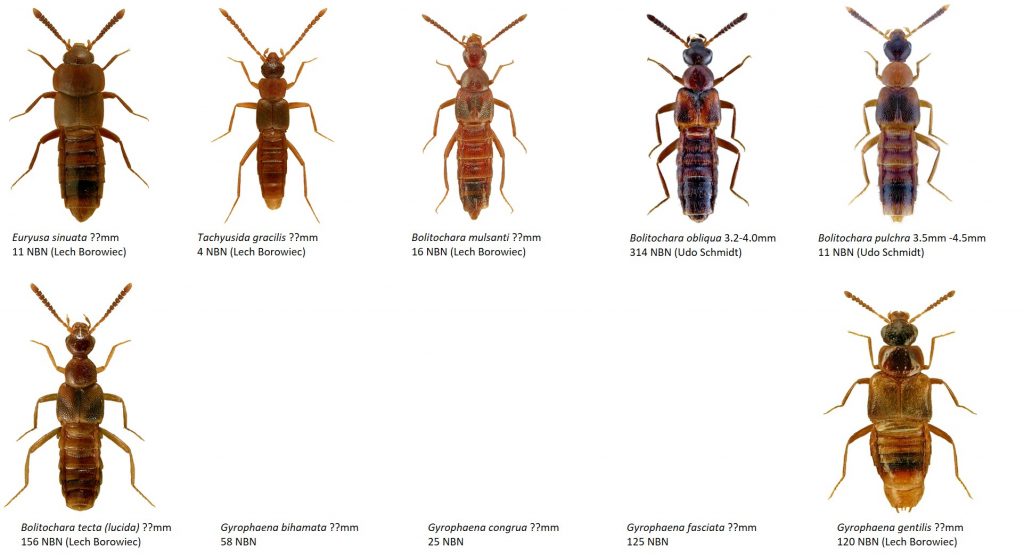

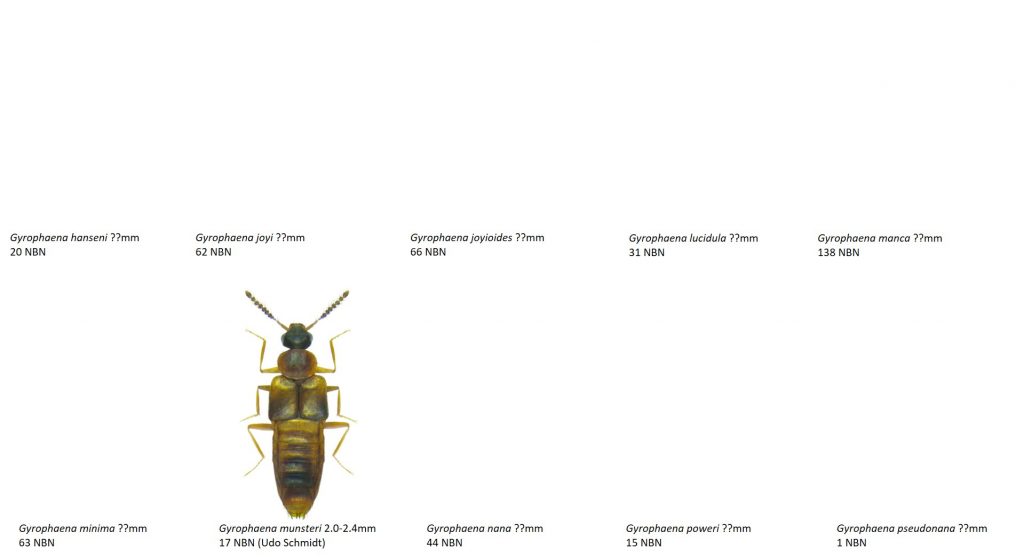

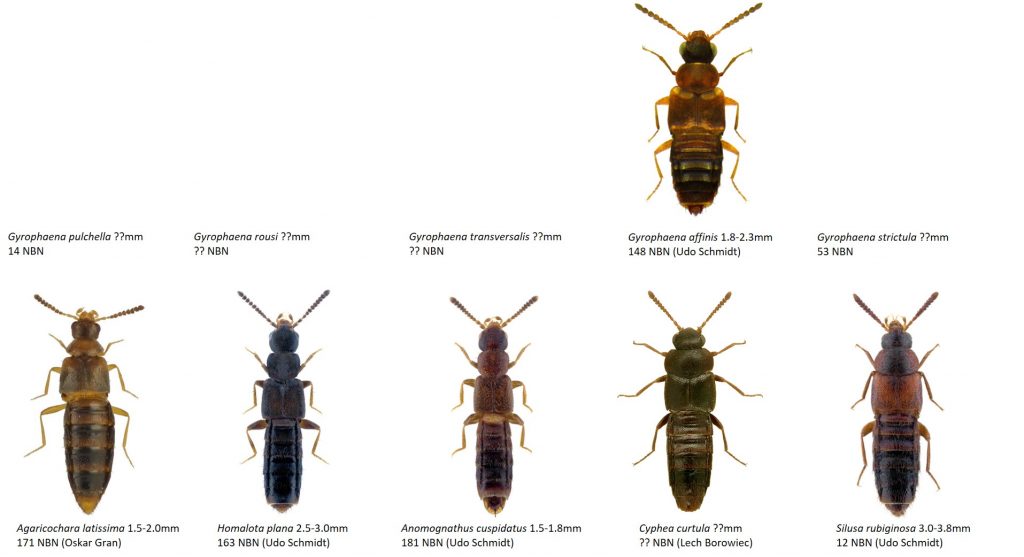

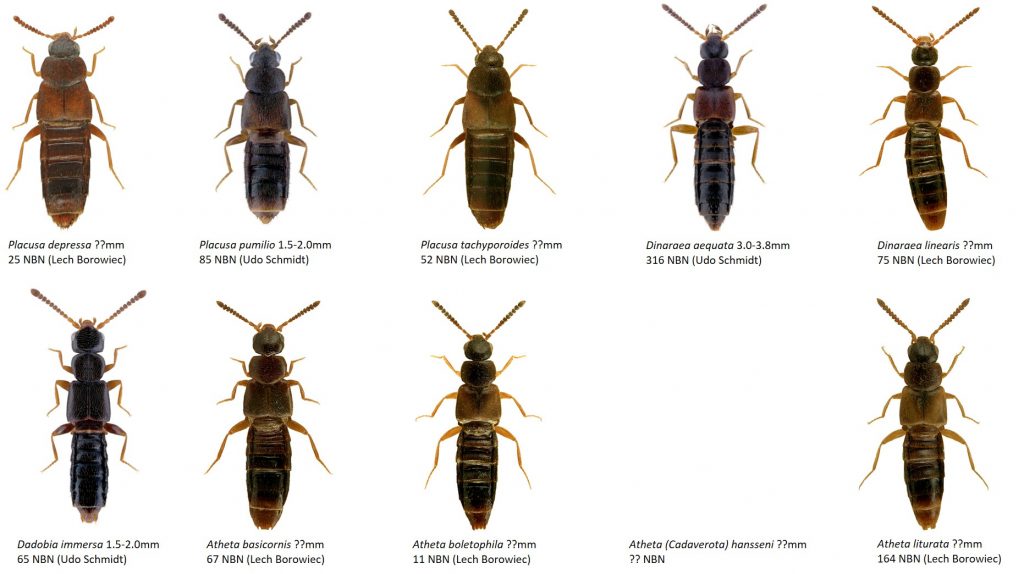

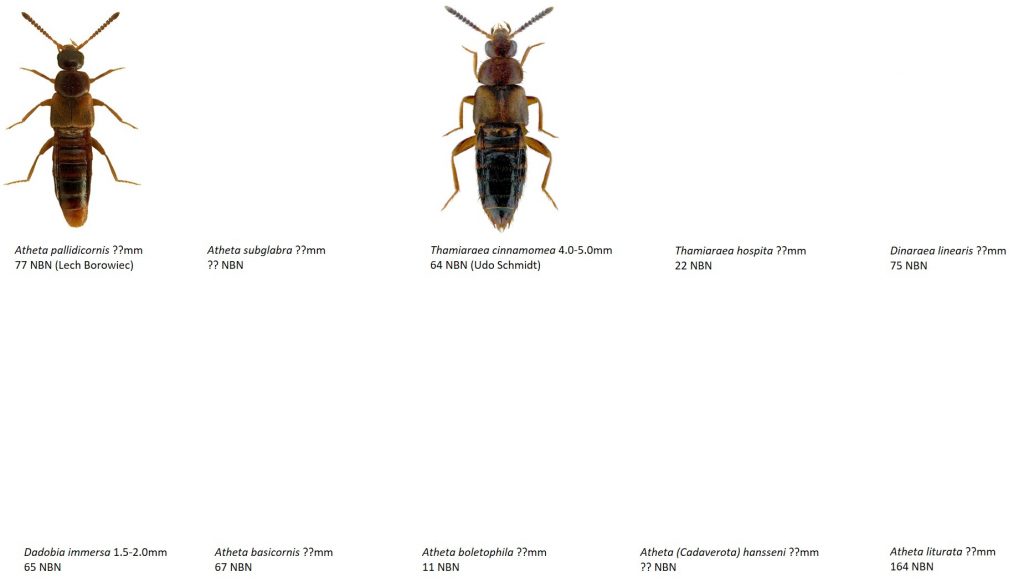

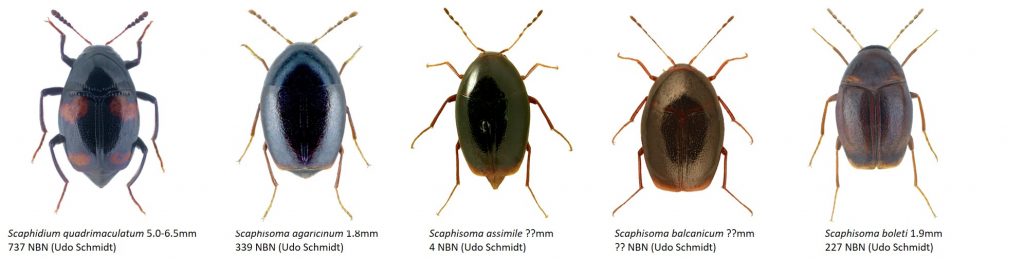

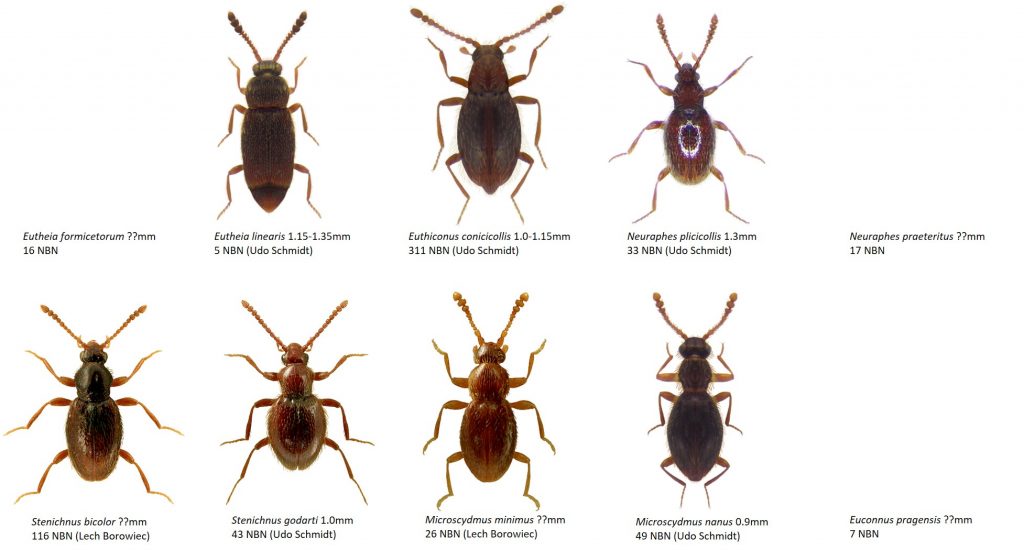

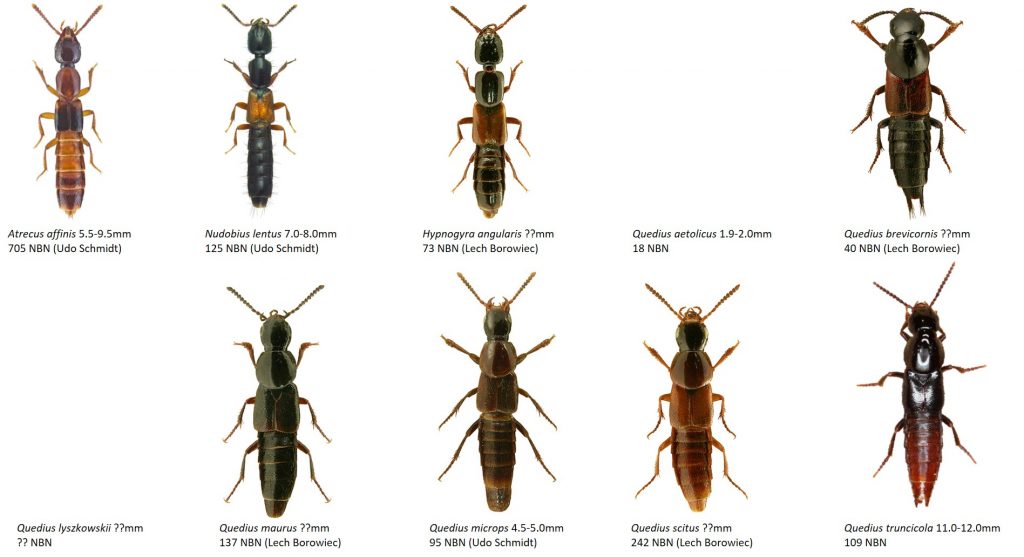

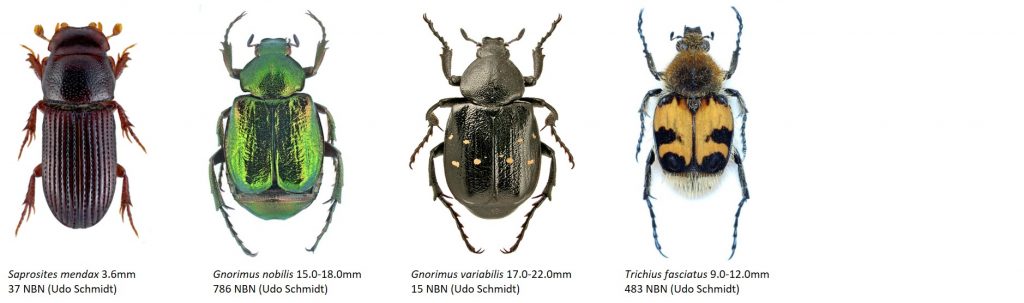

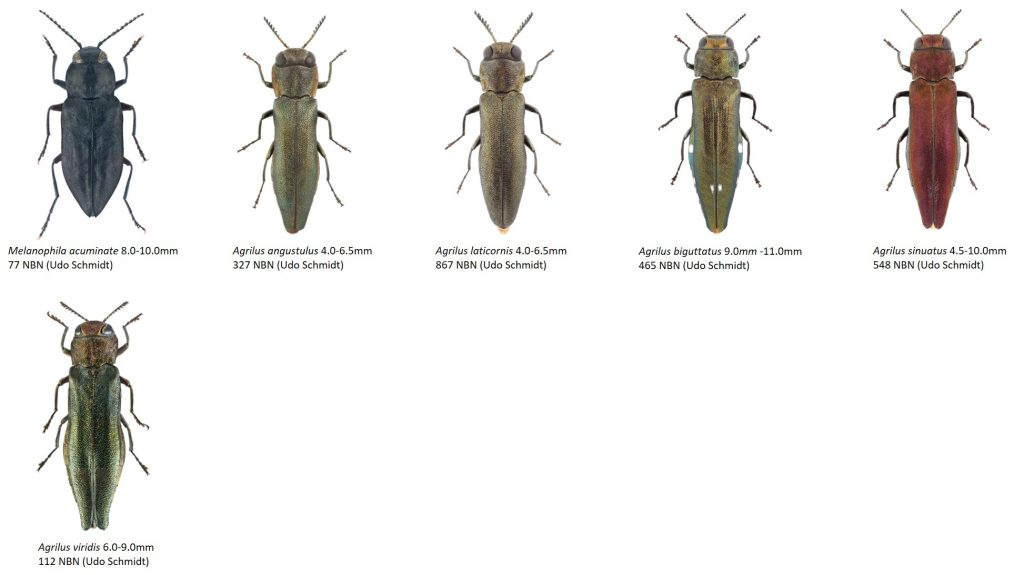

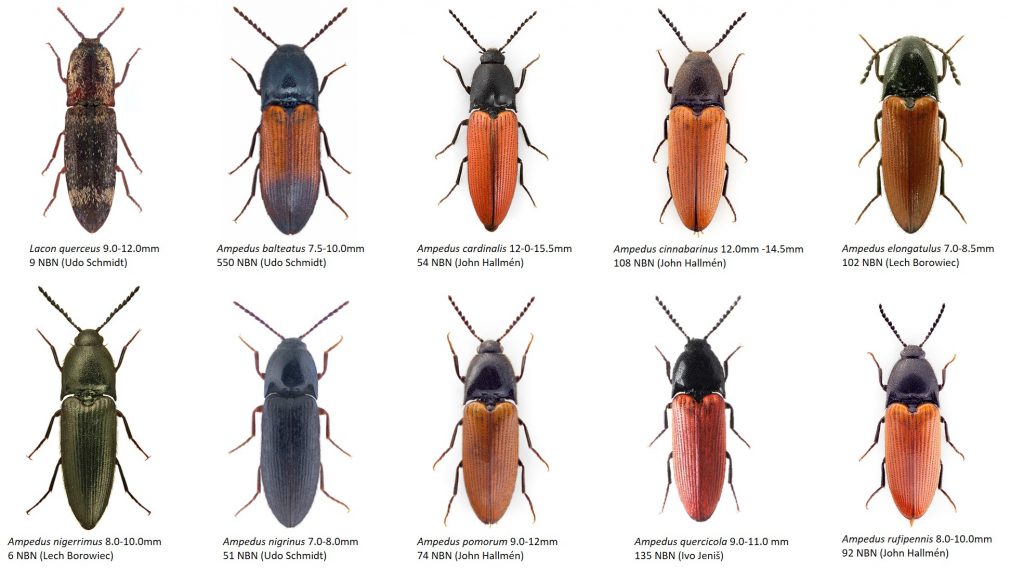

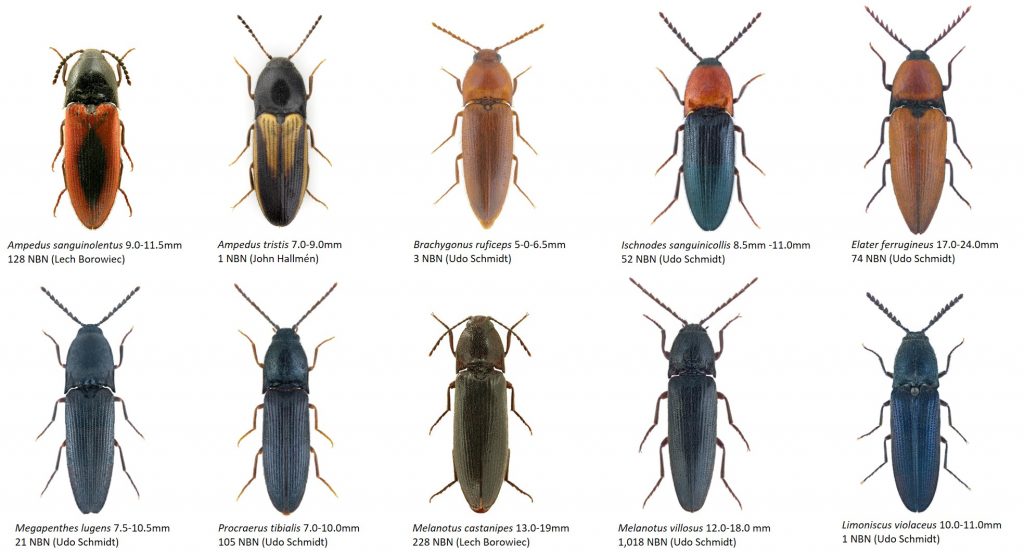

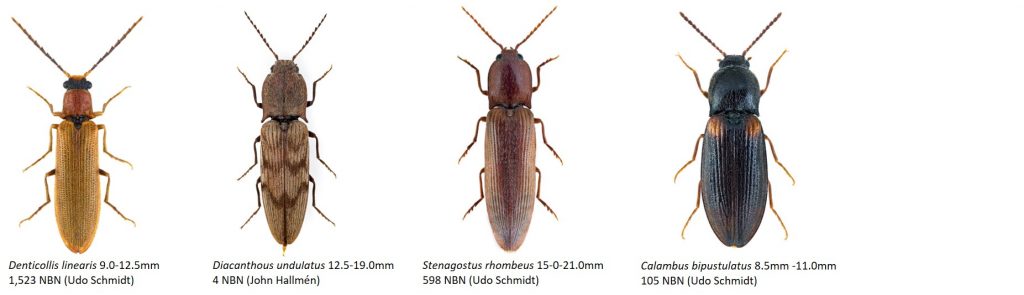

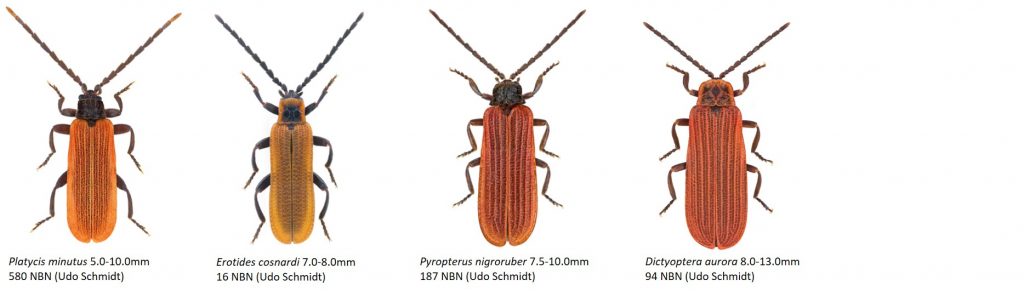

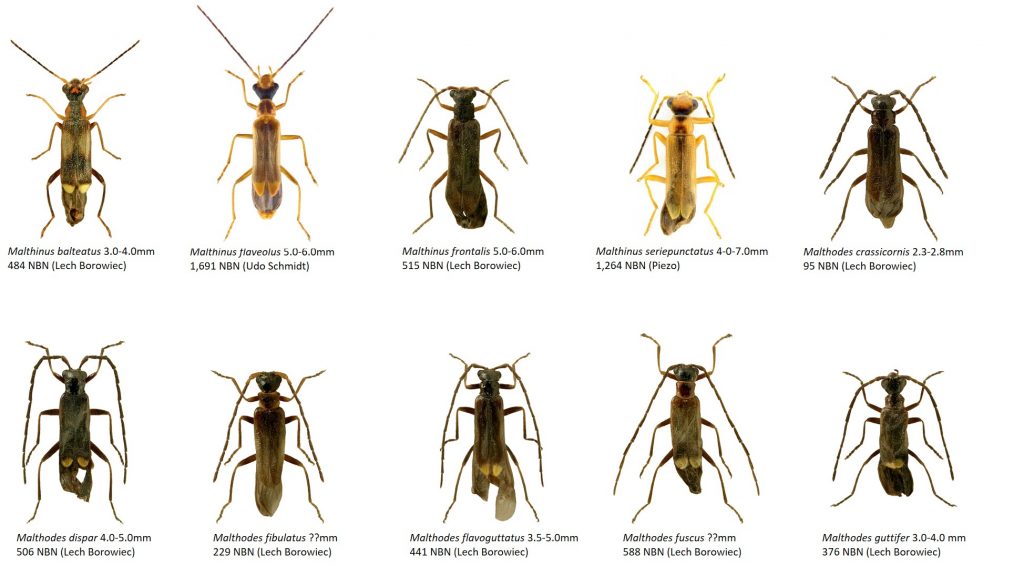

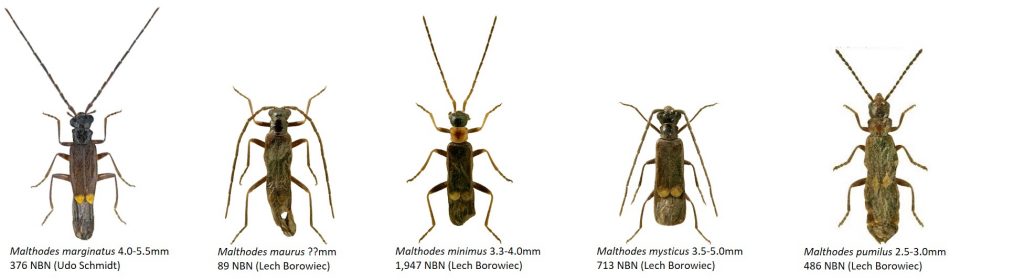

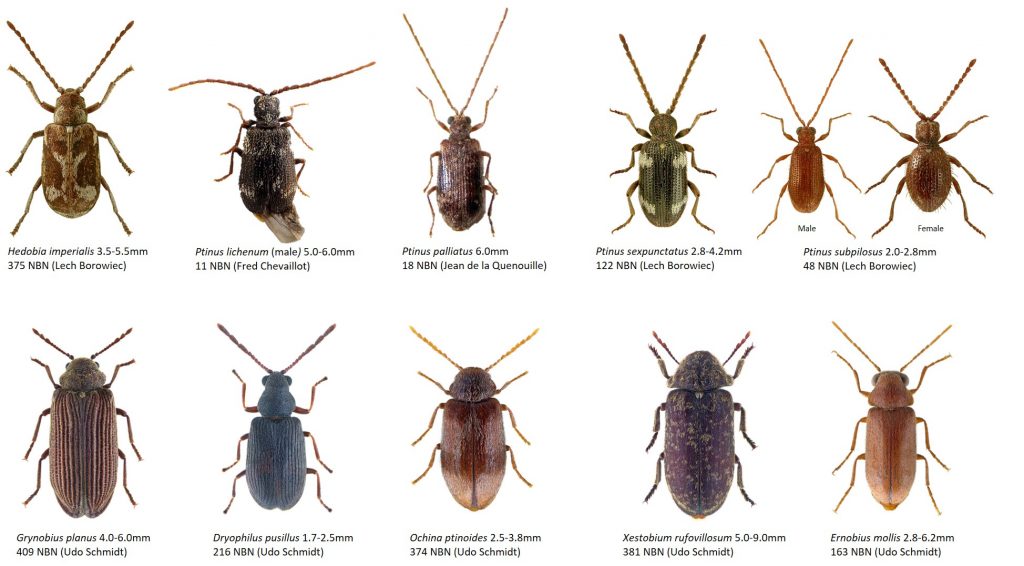

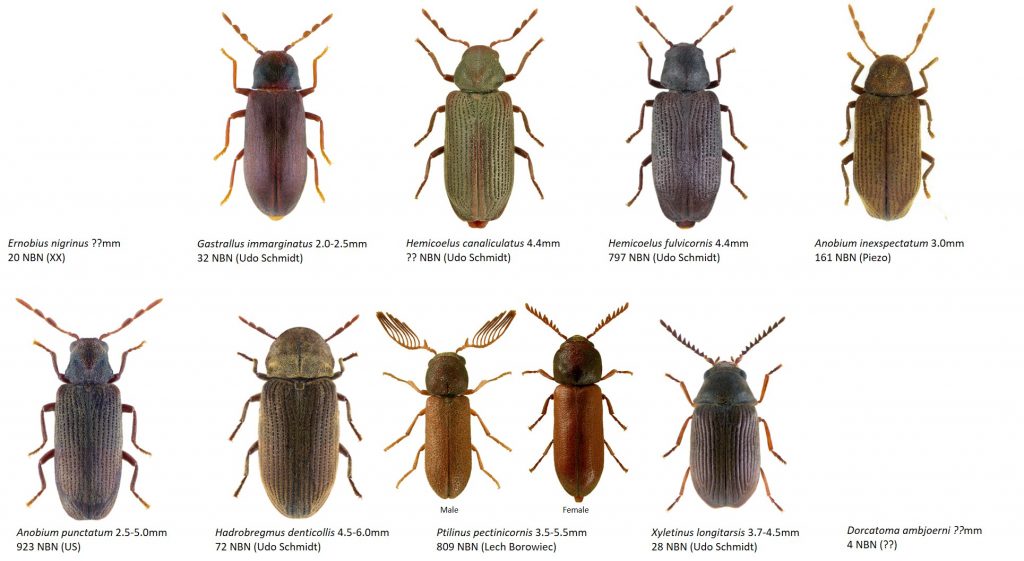

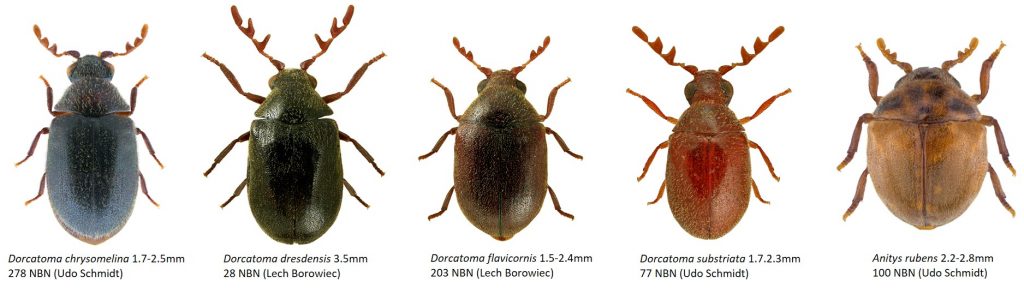

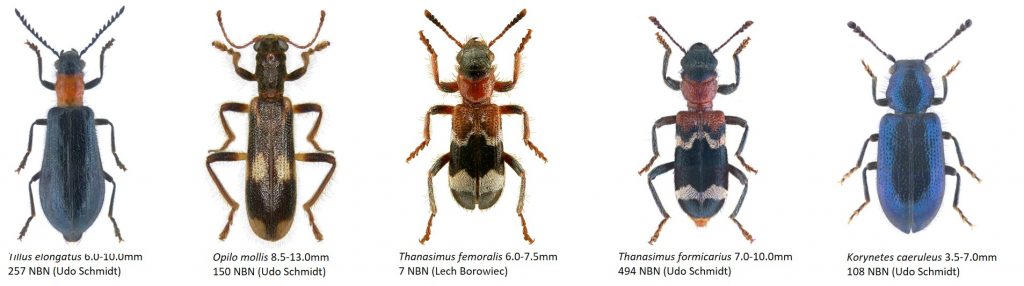

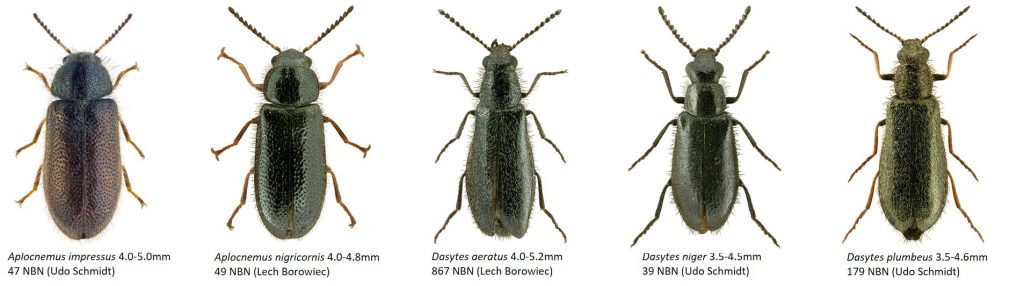

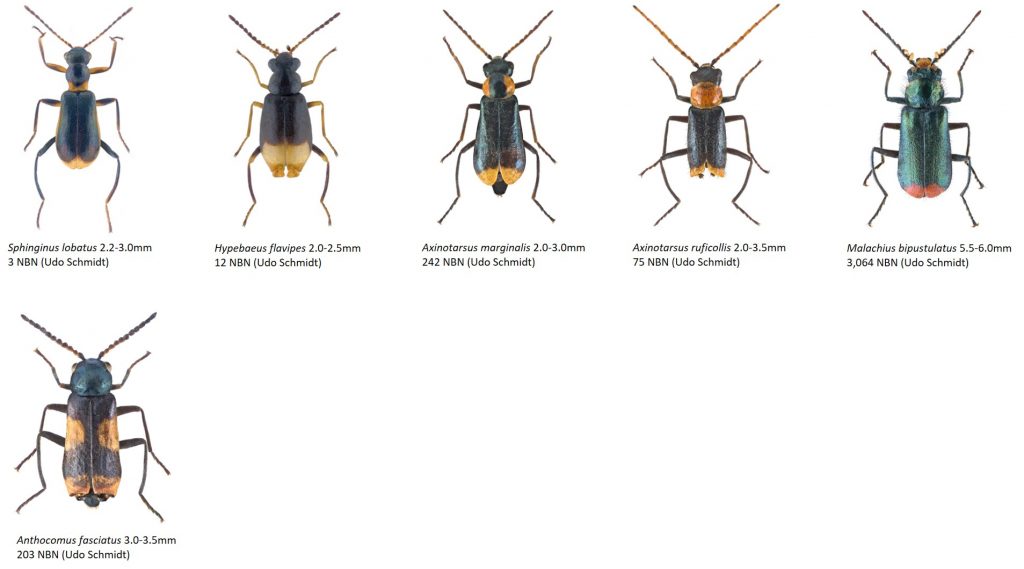

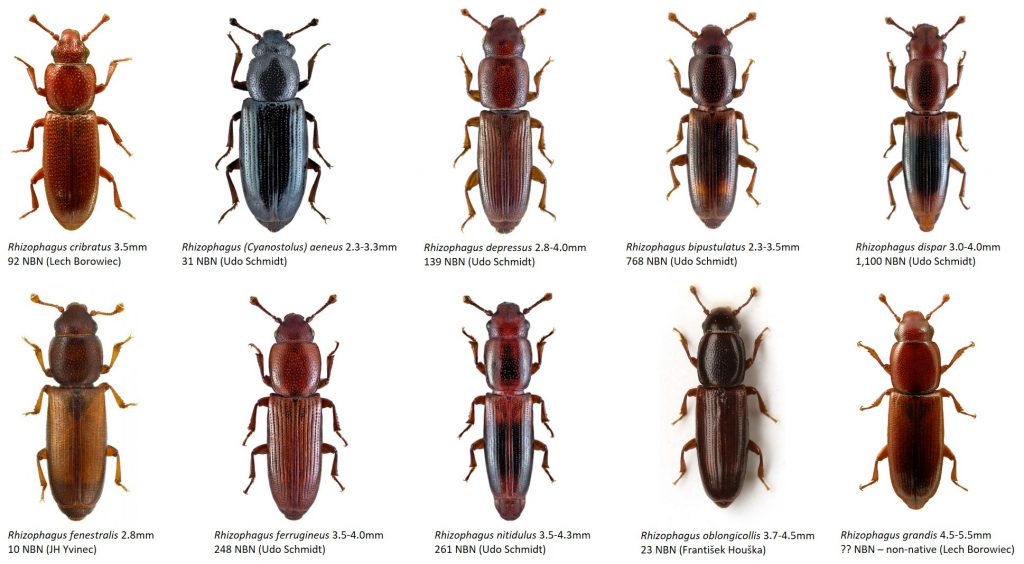

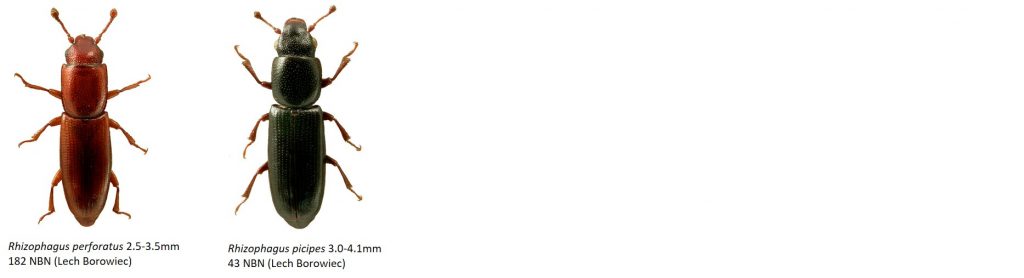

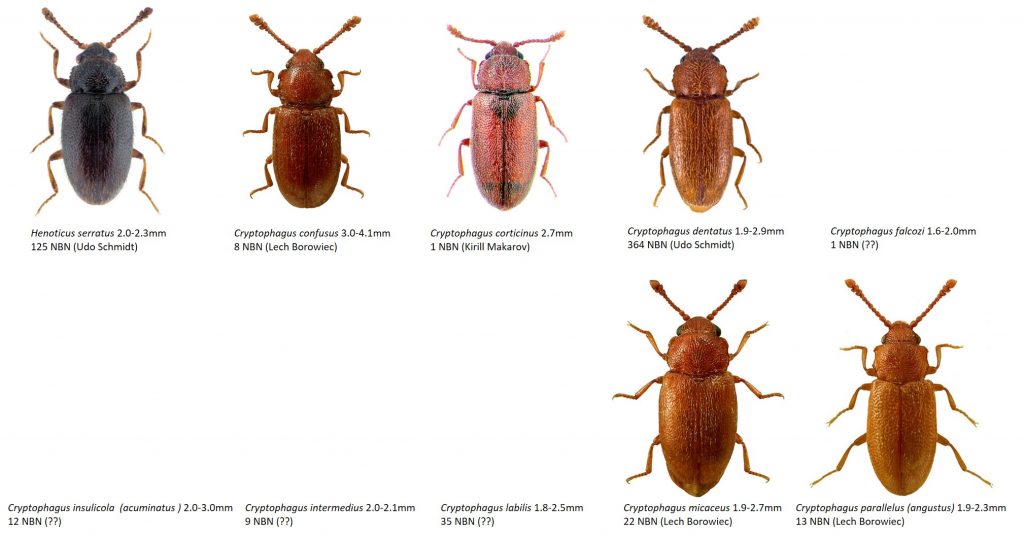

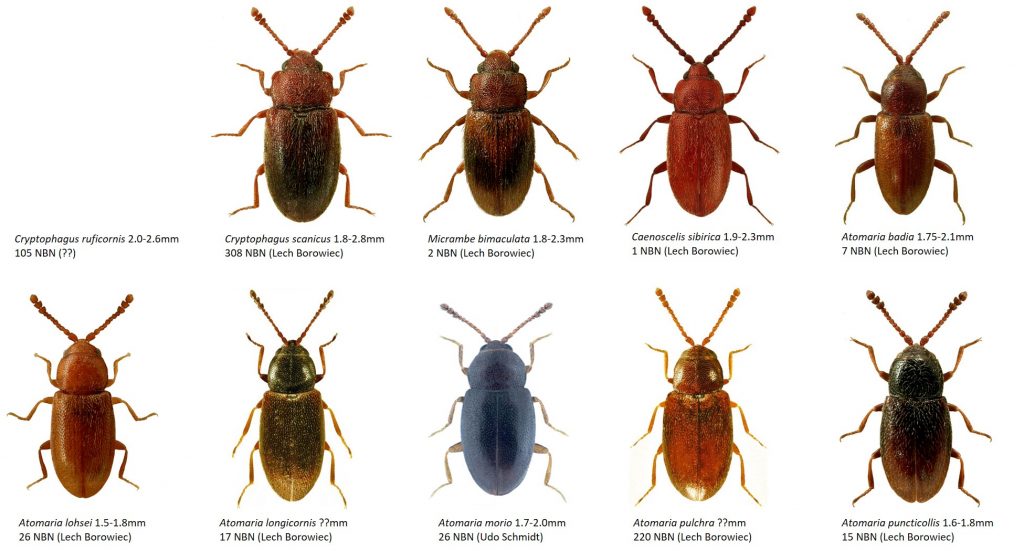

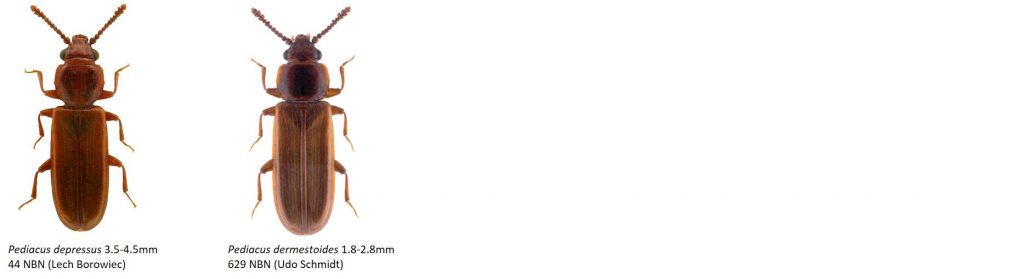

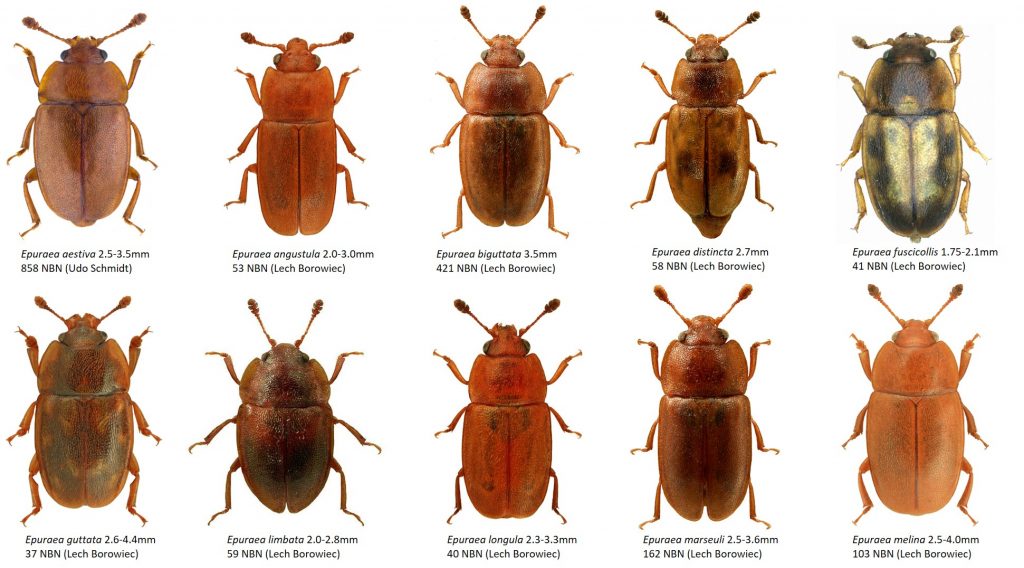

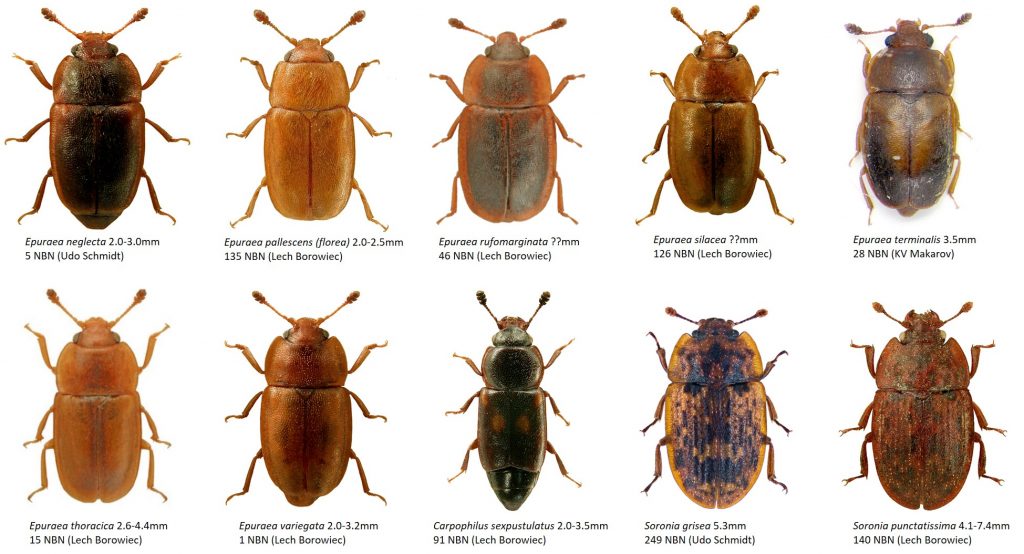

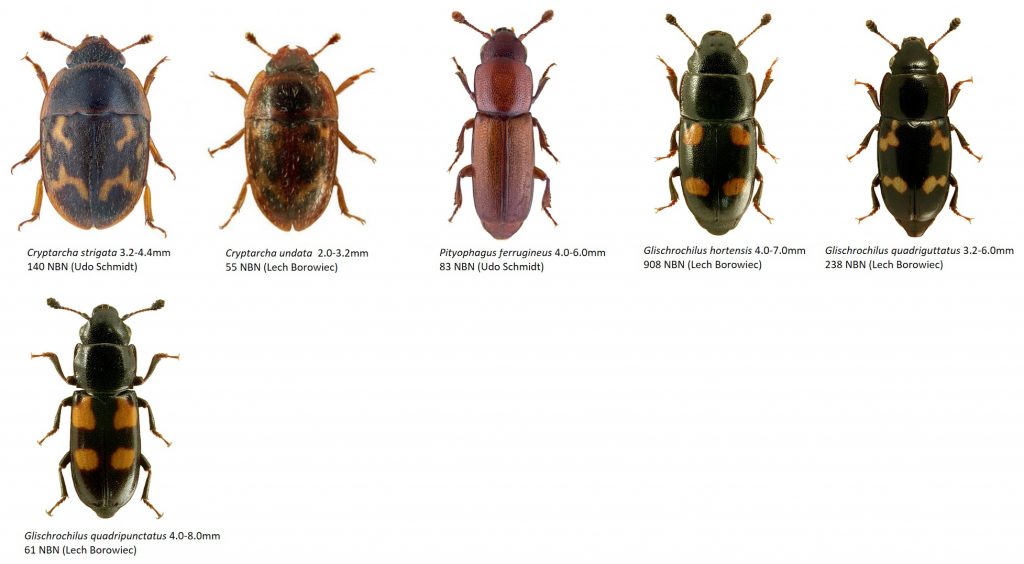

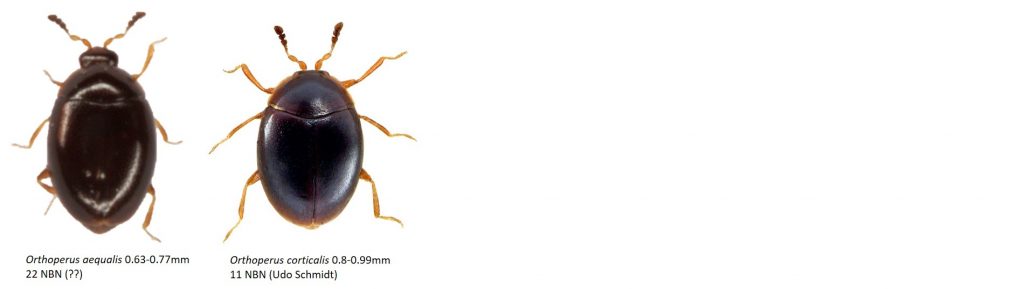

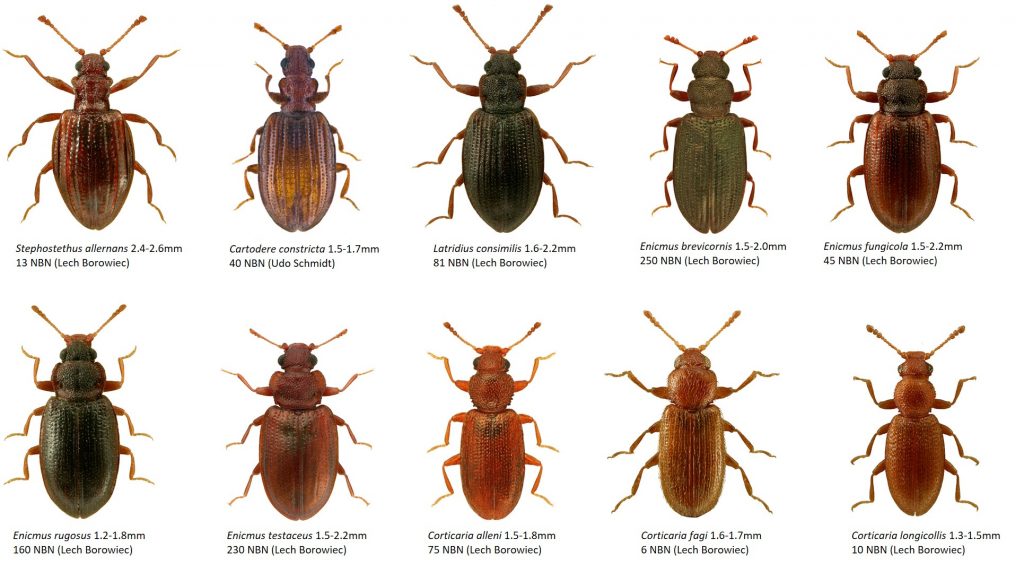

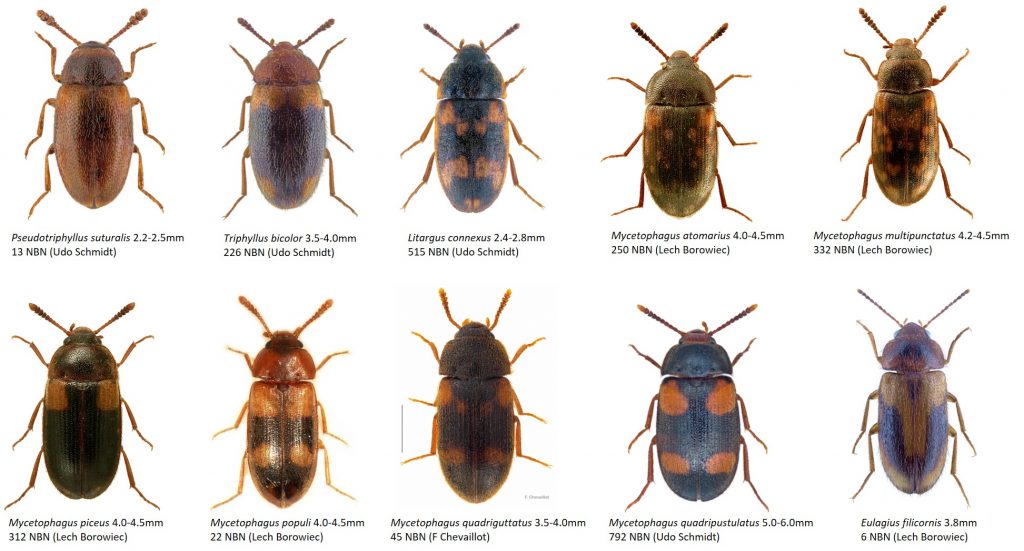

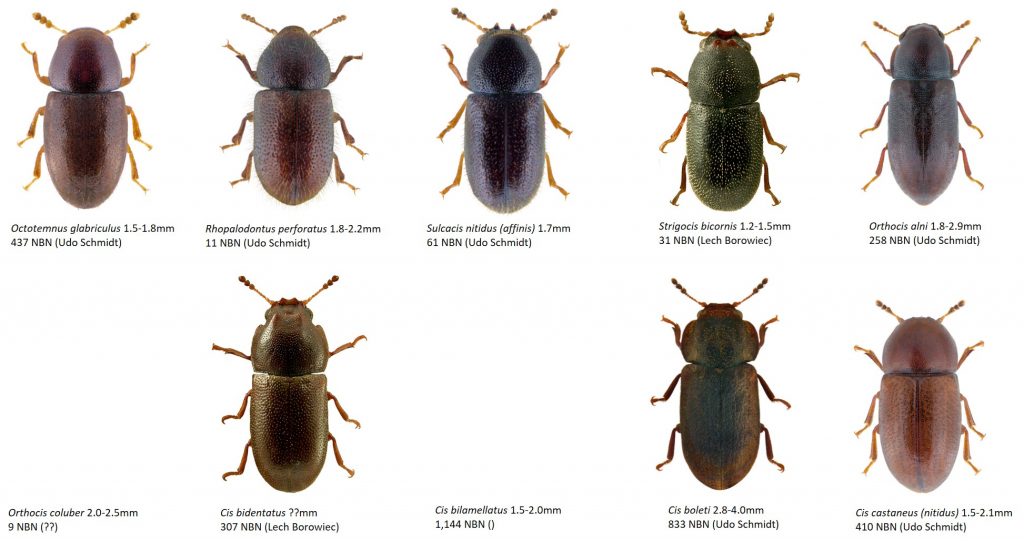

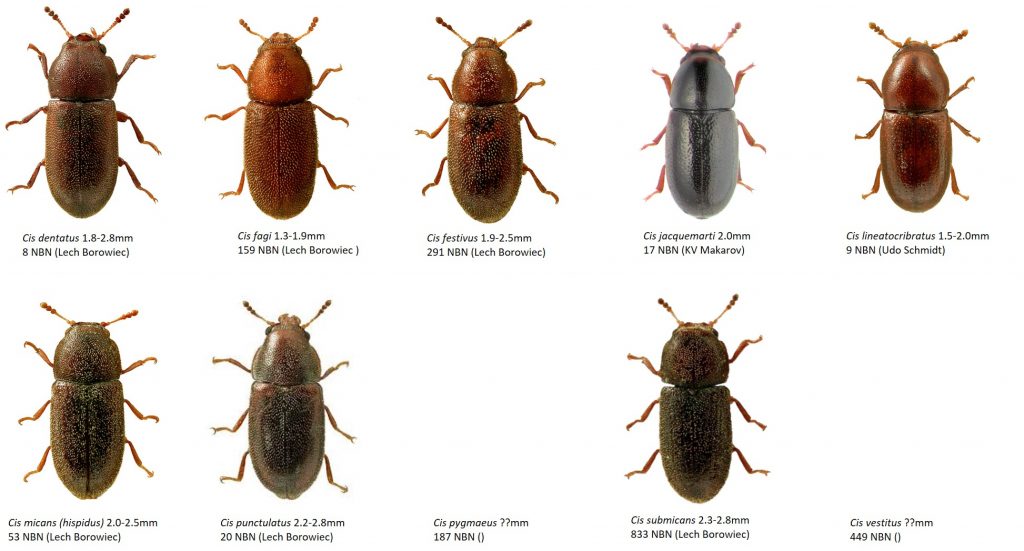

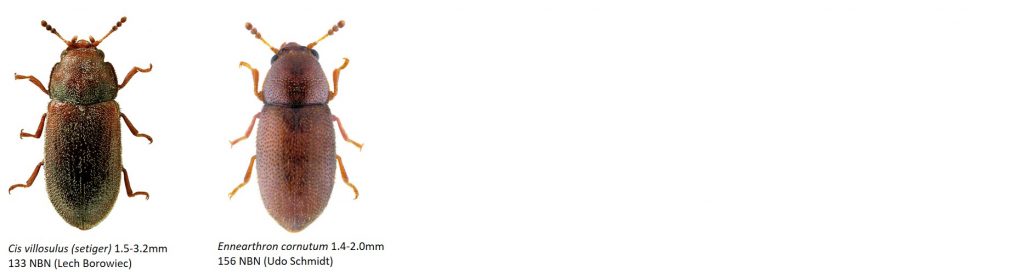

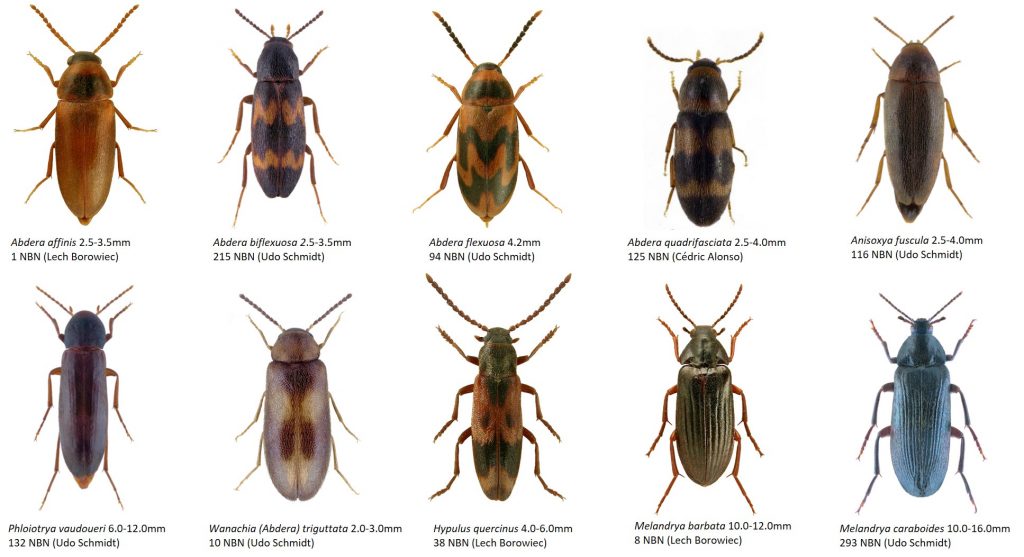

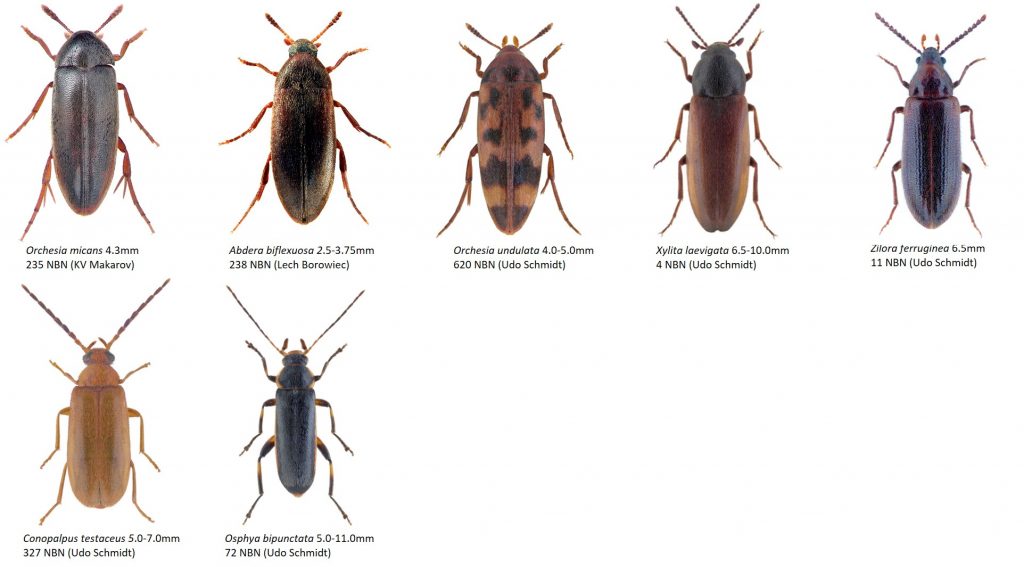

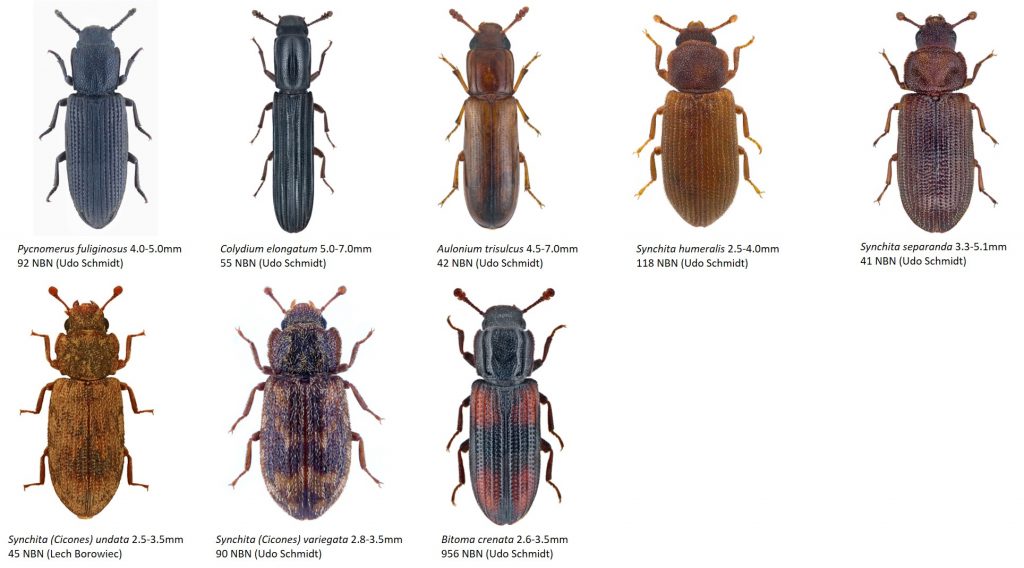

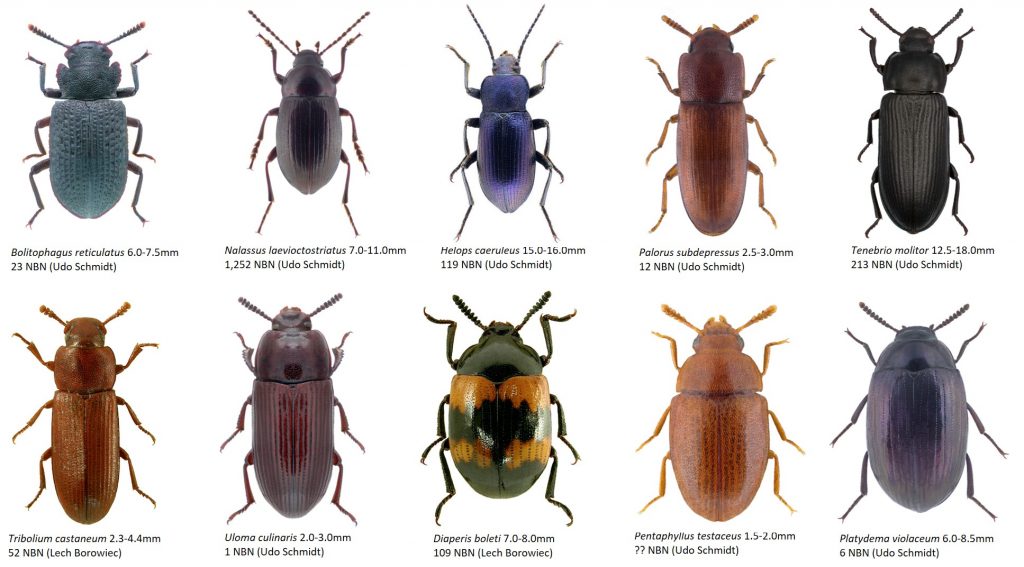

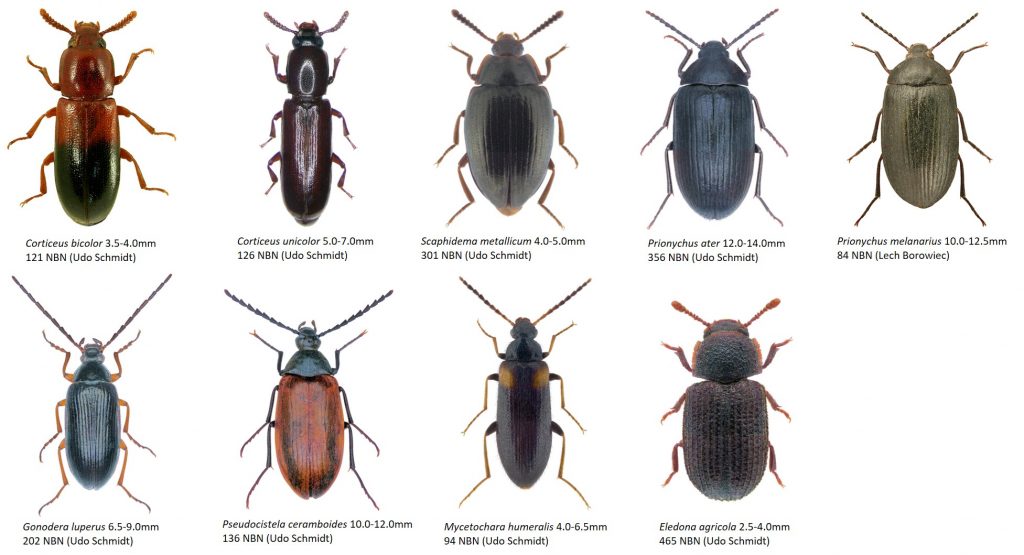

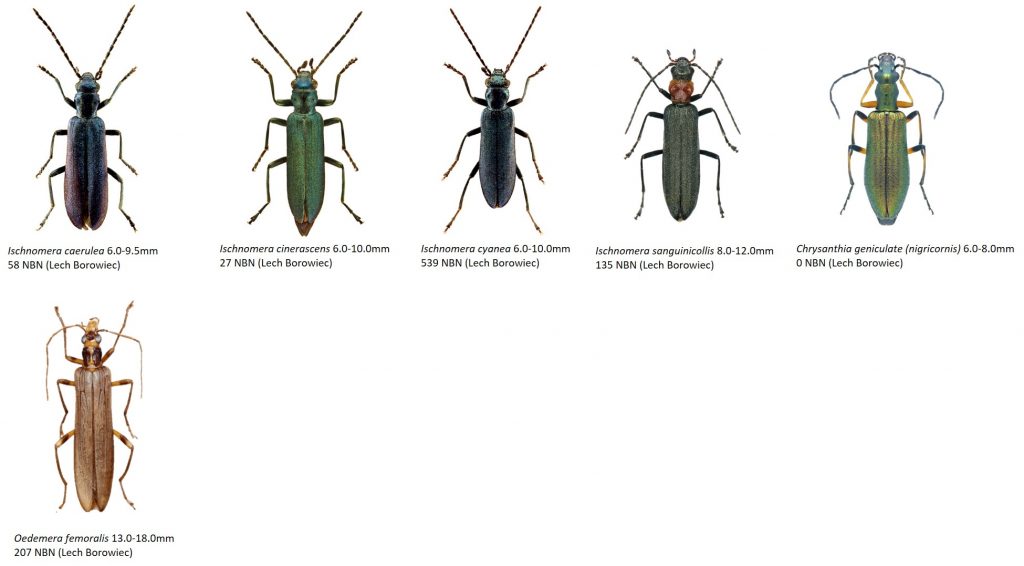

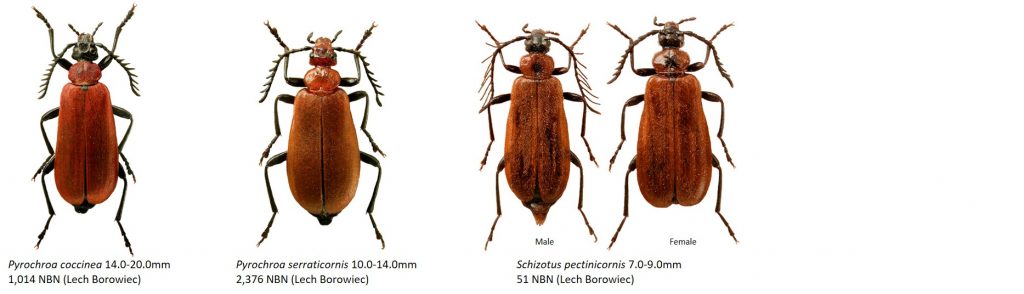

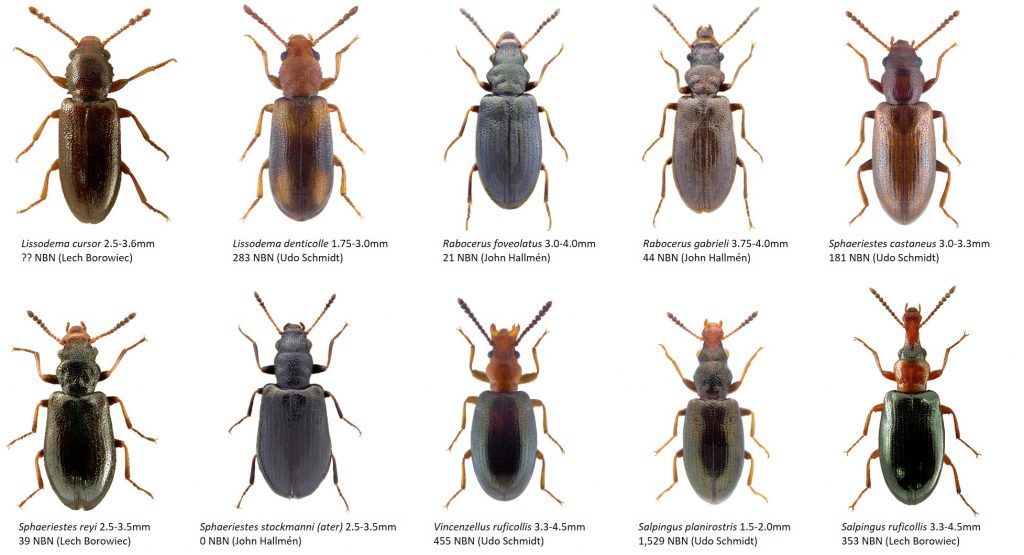

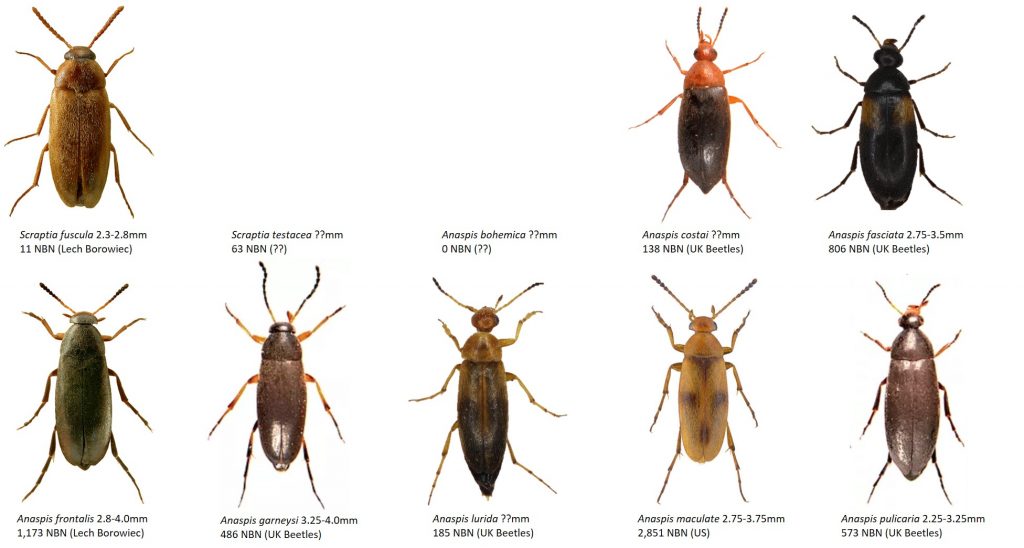

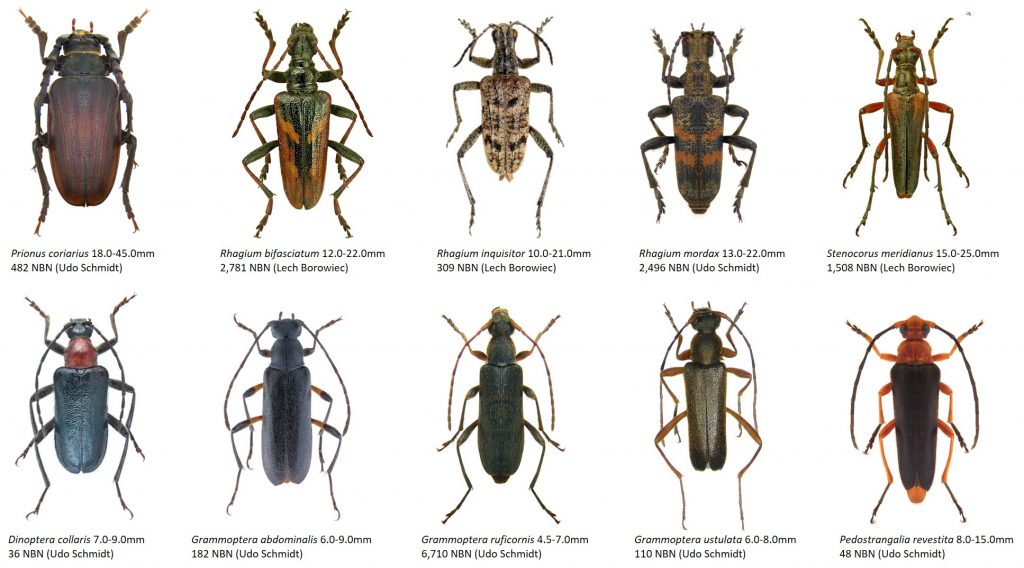

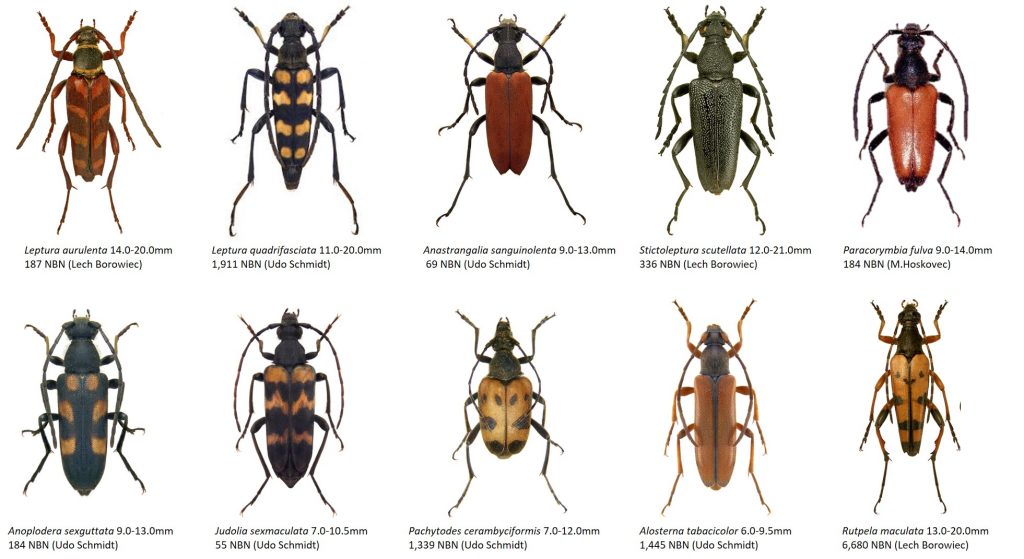

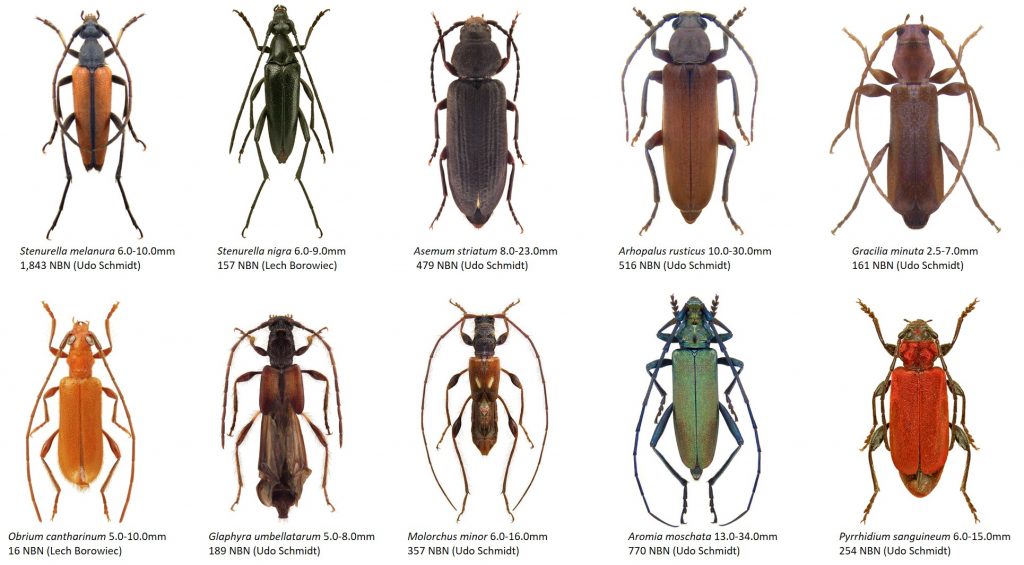

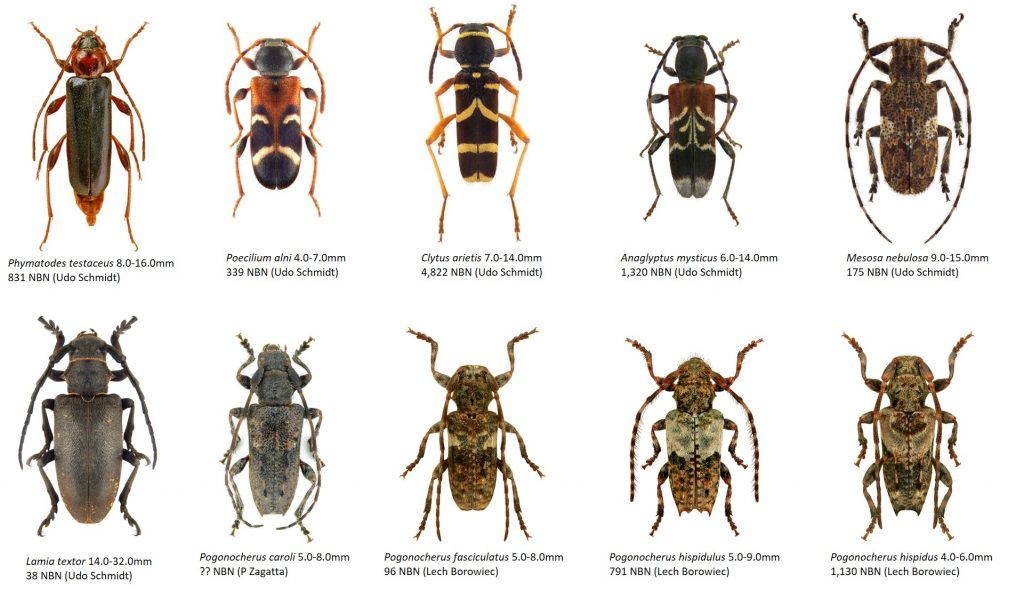

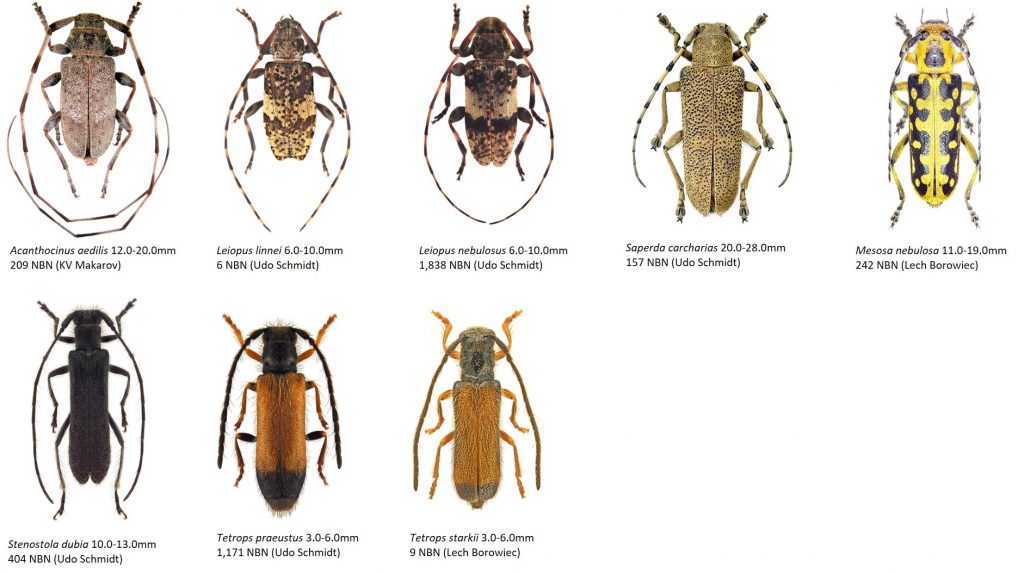

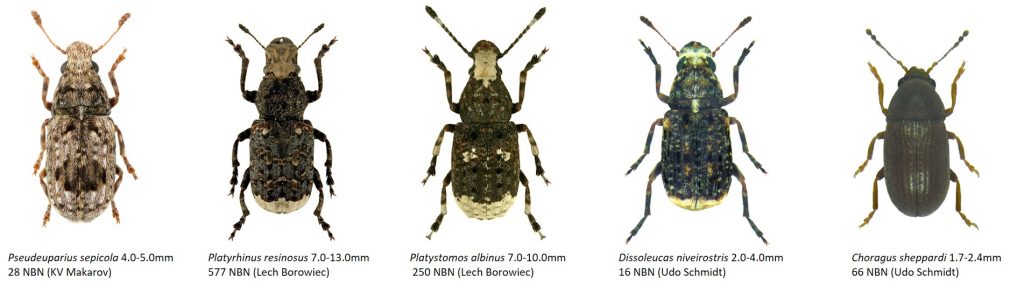

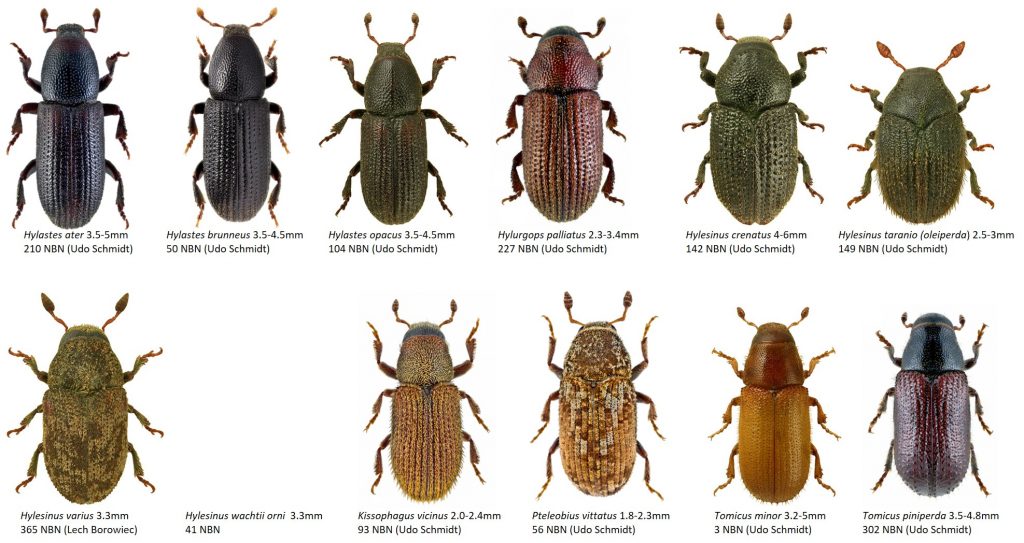

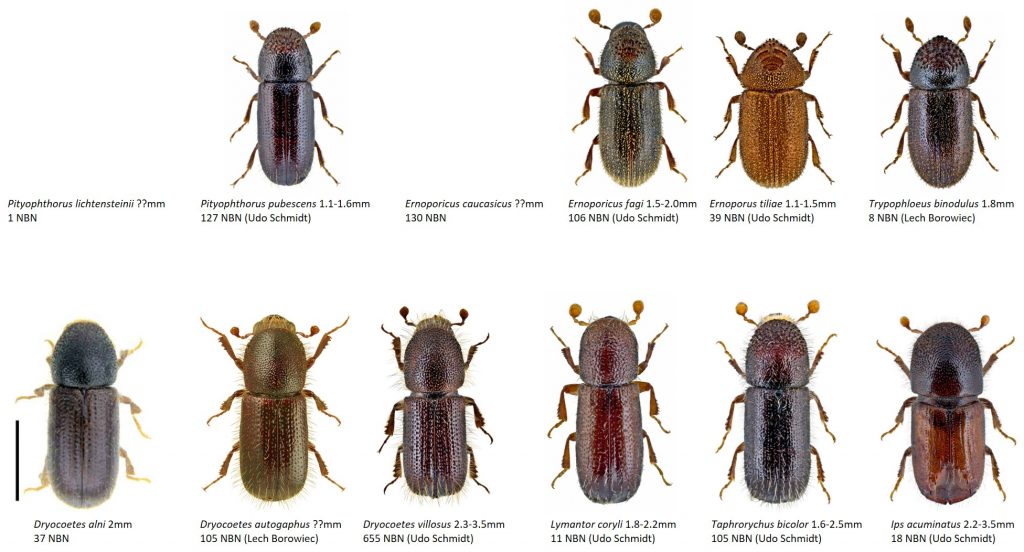

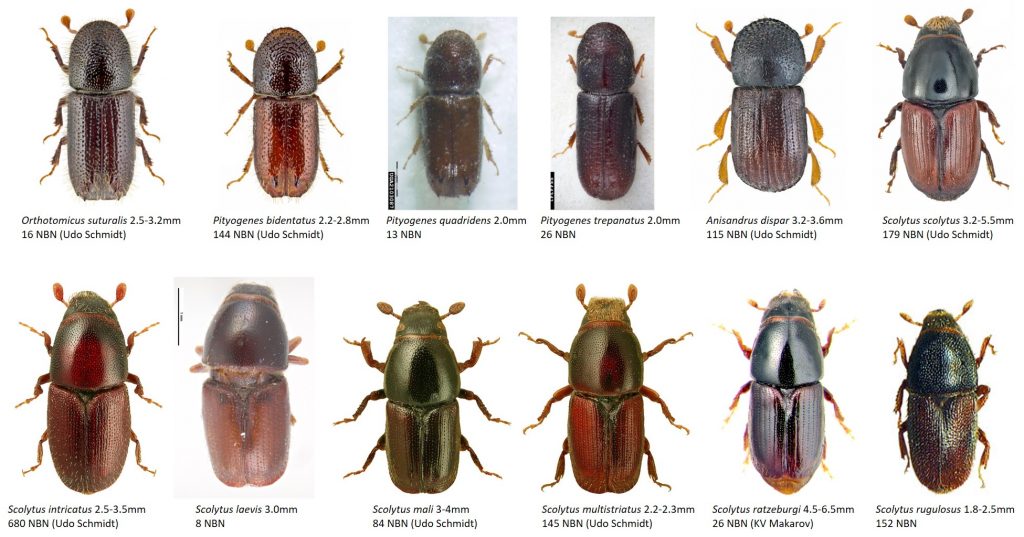

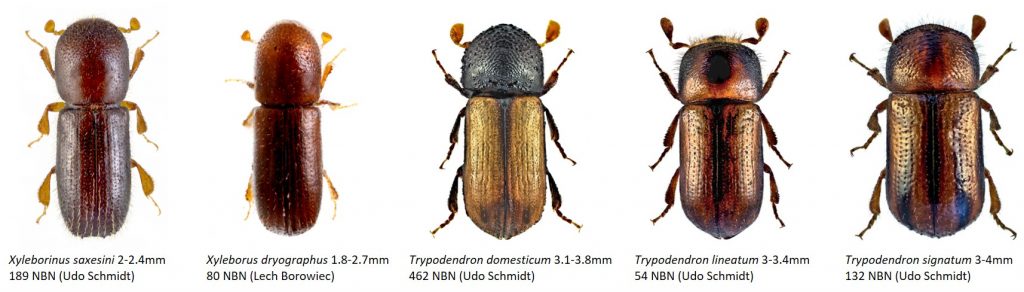

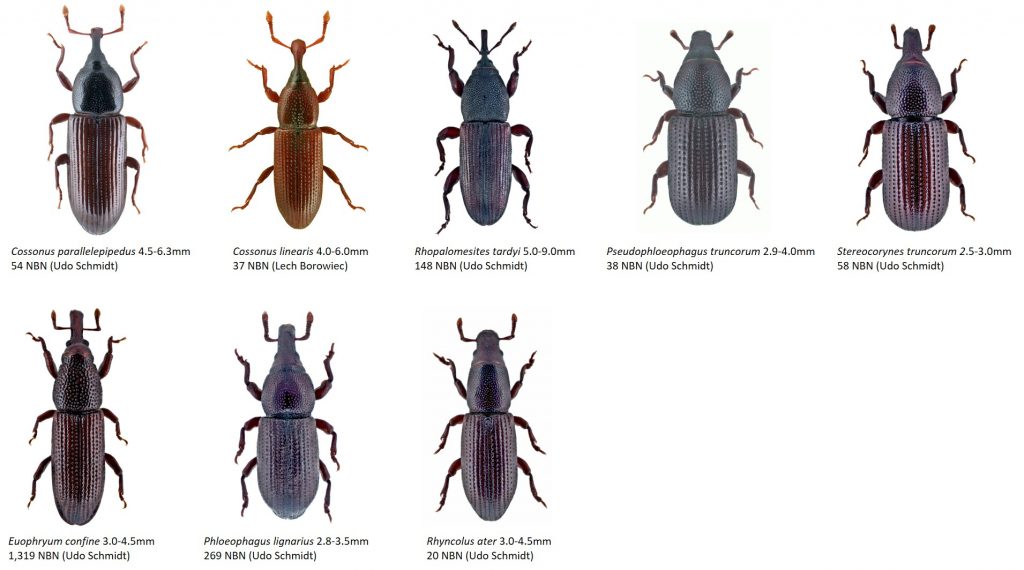

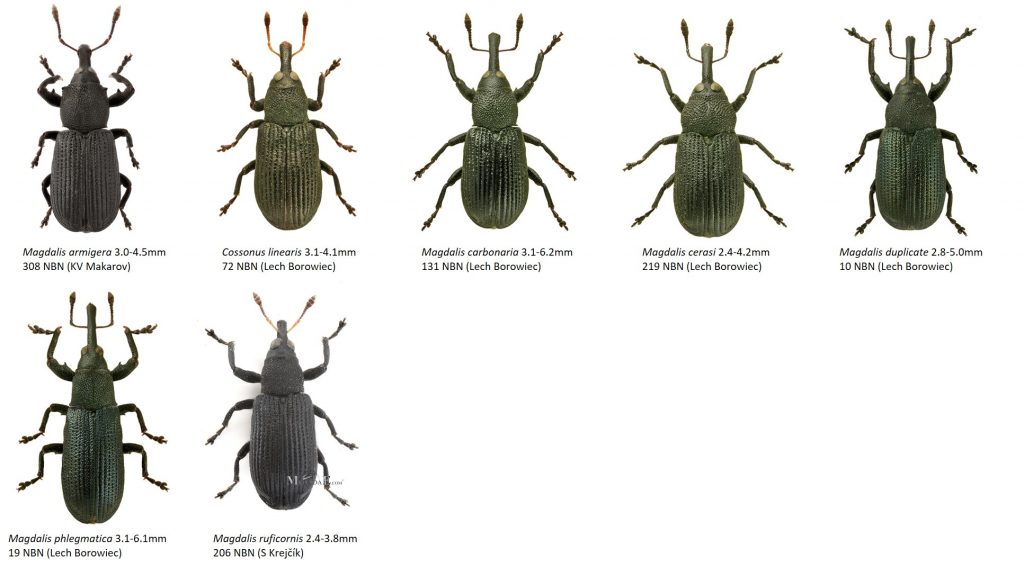

The extraordinary diversity of beetles in this habitat can make identification a bit of a challenge, so I’ve assembled photos and other details for most of the saproxylic beetles we have in the UK. There are some missing photos and details below, but I’ll add these when I get hold of them.

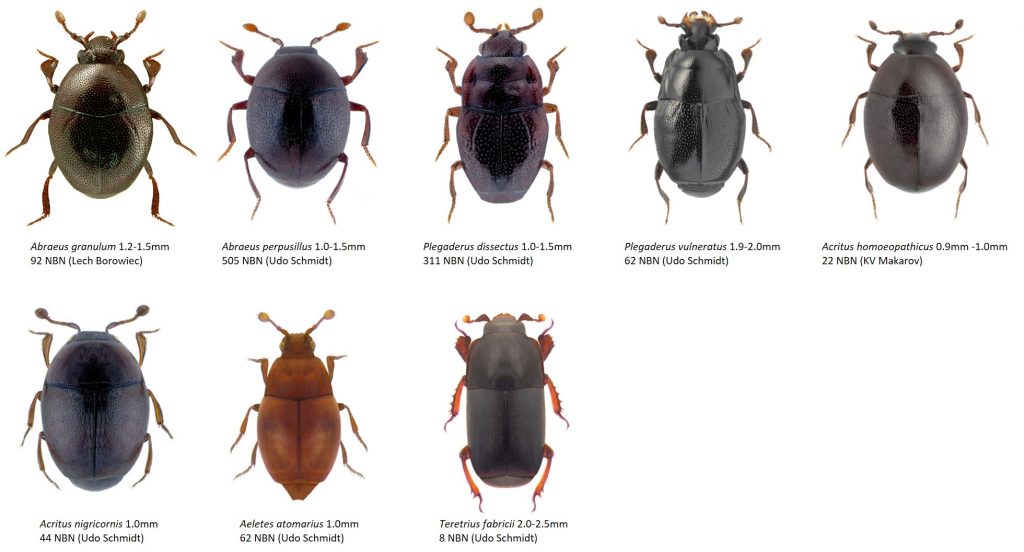

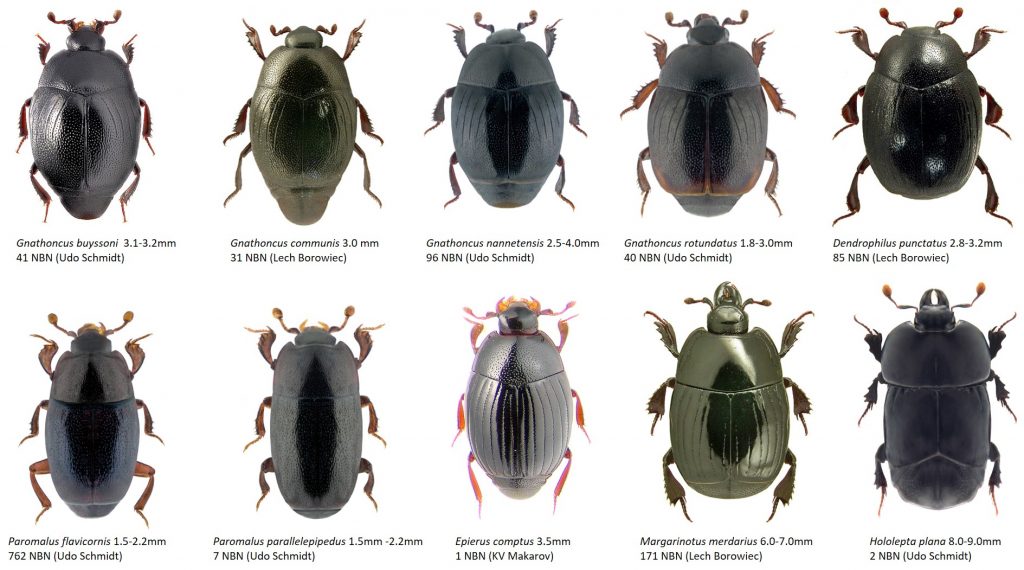

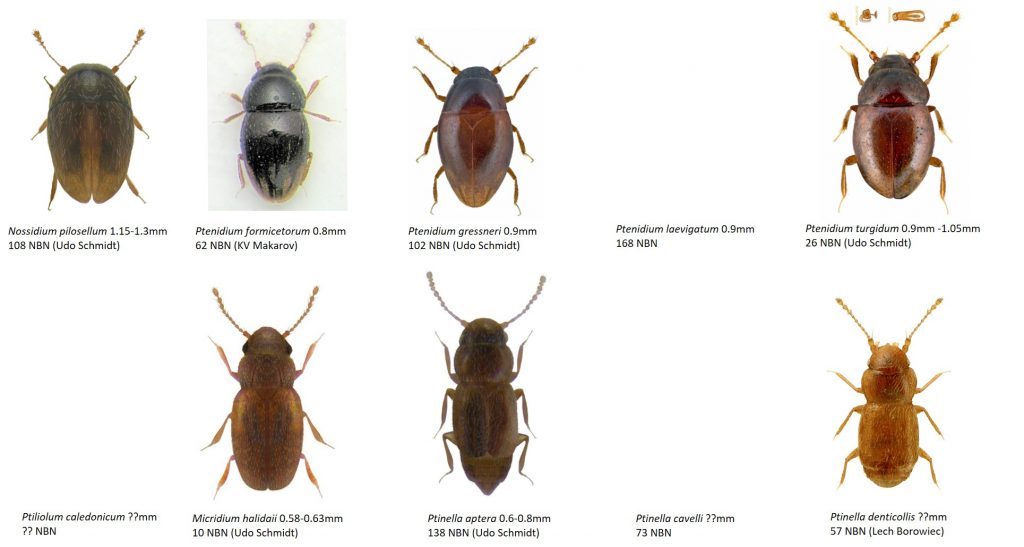

Beneath each photo is the scientific name, a size range, the number of records for that species from the NBN Atlas and copyright holder of the image. The number of NBN records gives you an indication of how common/well recorded the species is.

A good number of species are almost impossible to mistake for anything else, but there are also many that are very tricky to identify and for these the only way to be sure is to use a microscope and the relevant key. Mike Hackston’s key’s are a good place to start.

Most of the images below were taken by Udo Schmidt who has a superb Flickr site (images free to use under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence) and Lech Borowiec. Lech’s similarly superb images can be found on the impressive Biodiversity Map site. Dr Keith Alexander put together the list of saproxylic beetles.

The ecological information I’ve included is from The invertebrates of living and decaying timber in Britain & Ireland: A provisional annotated checklist (ENRR467) by Dr Keith Alexander and the superb UK Beetles site. Both of these resources are full of useful information.

Remember that there’s still masses to find out about the lives of every species here, so get out there and start filling in the gaps.

The entire guide can also be downloaded as a PDF.

Histeridae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae clubbed.

The saproxylic species range in size from 0.9mm to 9mm. Some are tricky to identify. Key

Predatory, especially on larvae of other deadwood insects, also mites and springtails.

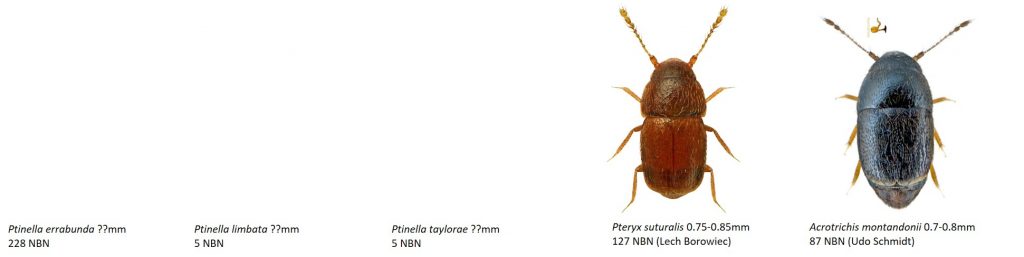

Ptiliidae

Tarsi simple. Antennae clubbed.

The saproxylic species range in size from 0.5mm to 1.3mm. Can be extremely hard to identify to species even with a key. Key.

Mould-feeders, living between the bark and sapwood of dead trees, where conditions are slightly moist and mouldy.

Photos and details are missing for a few of the species. These will be added when I get hold of them.

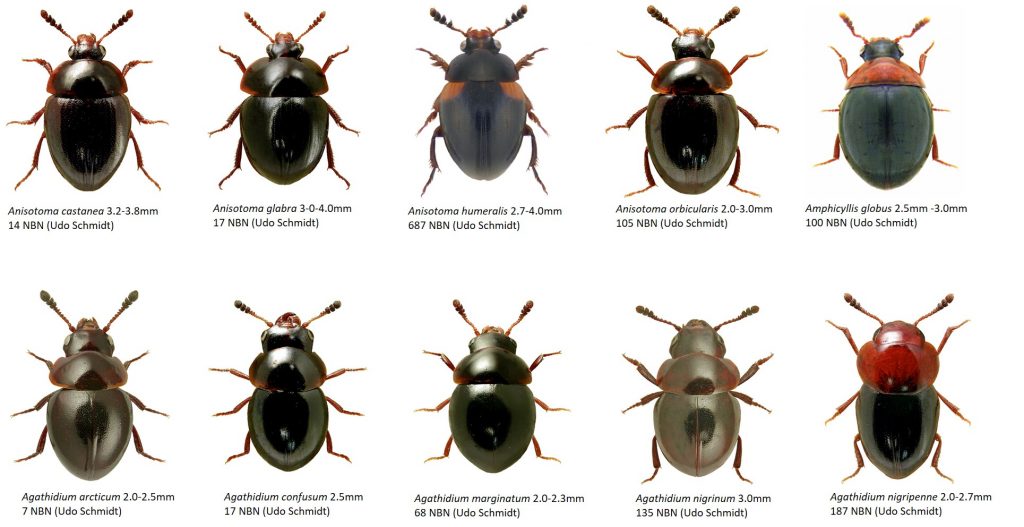

Leiodidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 or 5,5,4 or 5,3,3 or 4,3,3. Antennae clubbed or filiform. The saproxylic species range in size from 2.0mm to 4.0mm. Key.

Some species feed on carrion, others on subterranean fungi or on slime fungi (Myxomycetes) on dead wood. All species of Anisotoma have an obligate association with slime fungi, with adults and larvae feeding on the spores. Species of Agathidium are most likely primarily associated with slime fungi but the evidence is less clear.

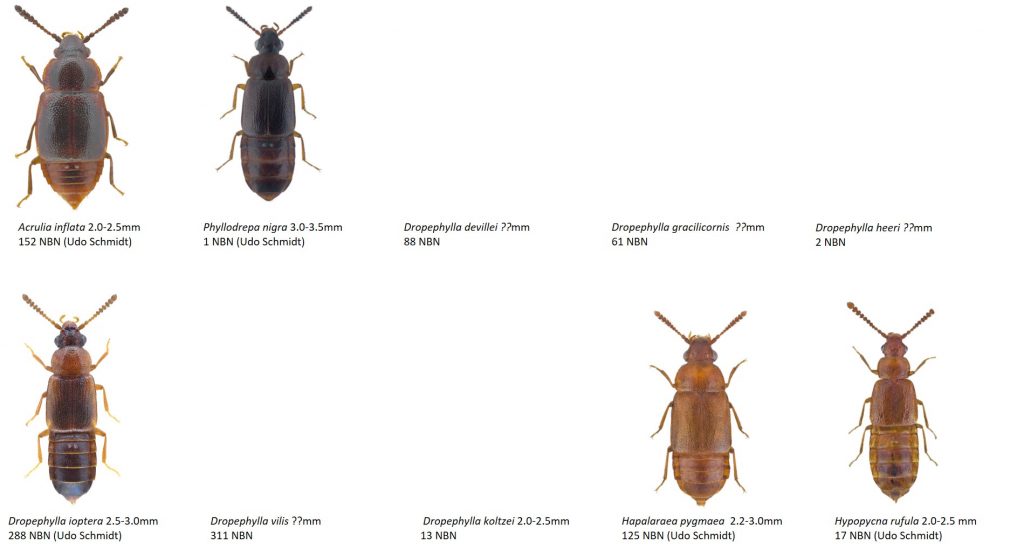

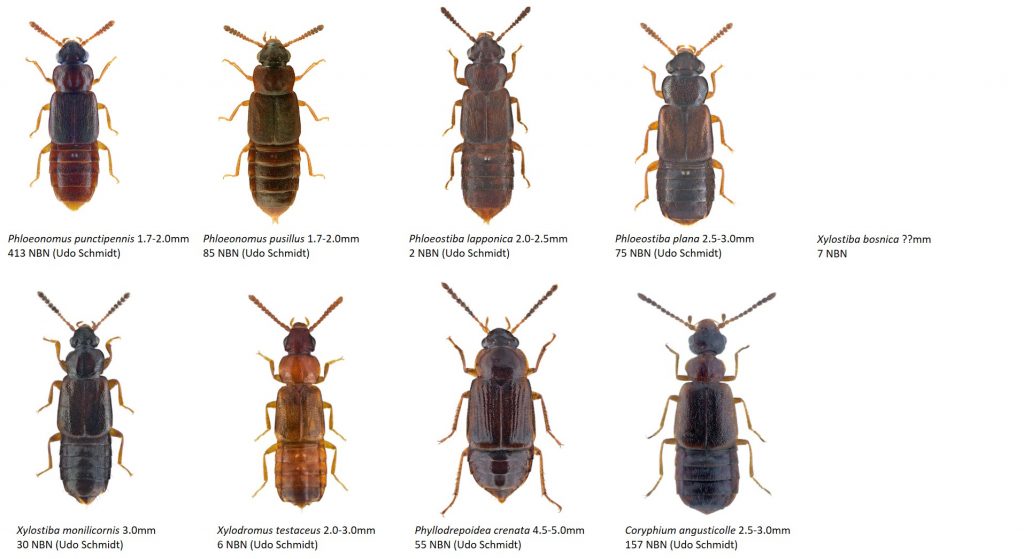

Staphylinidae: Omaliinae

The saproxylic species range in size from 2.0mm to 5.0mm. Generally tricky to identify to species. Key.

Staphylinidae: Proteininae

The saproxylic species ranges in size from 2.5mm to 3.0mm. Only 1 saproxylic species in the UK. Key.

Consistently associated with decaying fungi, including beefsteak Fistulina hepatica.

Staphylinidae: Pselaphinae

The saproxylic species range in size from <1mm to 3.0mm.

Many of these are tiny, but identification to genus is fairly straightforward. Key. The genus Euplectus contains several, morphologically very similar species.

Predatory, particularly on mites; a number associated with deadwood. Some are associated with ants that make their nests in dead and decaying wood. Exactly what they do in these nests is poorly known.

Staphylinidae: Phloeocharinae

The saproxylic species ranges in size from 0.8mm to 1.0mm. Only 1 saproxylic species in the UK.

Amongst debris under beech Fagus bark, in moss on trees, on bracket fungi especially Daedaleopsis confragrosa on Salix, etc.

Staphylinidae: Tachyporinae

The saproxylic species range in size from 2.0mm to 6.0mm. Identification can be tricky. See the Käfer Europas Key

Staphylinidae: Aleocharinae

The saproxylic species range in size from 1.5mm to 5.0mm.

Nightmare. A huge group of beetles with lots of similar genera, many of which with lots of morphologically very similar species. See Mike Hackston’s ongoing keys to this sub-family. Other keys can be found online. Photos and details are missing for many of the species. These will be added when I get hold of them.

Staphylinidae: Scaphidiinae

The saproxylic species range in size from 1.8mm to 6.5mm.

Distinctive and very pleasing beetles. The genus Scaphisoma can be a little bit tricky. Key.

Associated with fungoid wood, fleshy and bracket.

Staphylinidae: Piestinae

A single a distinctive saproxylic species that ranges in size from 4.5mm to 5.0mm.

Under moist bark on various broad-leaved trees, especially elm Ulmus; saprophagous

Staphylinidae: Scydmaeninae

The saproxylic species range in size from 0.9mm to 1.5mm. Fairly distinctive, but tiny beetles. Tricky to identify to species. Key.

Predatory on mites, in moist situations.

Staphylinidae: Staphylininae

The saproxylic species range in size from 1.9mm to 24.0mm.

Some very distinctive genera and species, but some tricky ones. Key for some species. Other keys can be found online.

Trogidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae with lamellate club. A single a distinctive saproxylic species that ranges in size from 5.0mm to 8.0mm.

Adults and larvae occur in bird nests, especially those in hollow trees e.g. owl nests that contain pellets and animal detritus. Adults may be attracted to light, carrion or old bones. See UK Beetles for more information.

Lucanidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae with lamellate club. Three large (12.0mm to 70.0mm), unmistakable species. Female Lucanus look superficially similar to Dorcus.

See UK Beetles for lots more information on the Lucanidae generally and the UK species.

Scarabaeidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae with lamellate club. Four small to large (3.5mm to 22.0mm), unmistakable species.

S. mendax (Blackburn) was introduced accidentally from Australia and is now established in the southeast. It has been reported from Dorcus and Sinodendron burrows and from under bark

See UK Beetles for more information on the Cetoniinae, the sub-family to which the other saproxylic species belong.

Scirtidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 with some bilobed segments. Antennae filiform. A single, fairly distinctive species that ranges in size from 3.5mm to 4.8mm.

Develops in water-logged hollows in old trees, especially beech Fagus, and including hollows amongst roots; larvae aquatic, feed on detritus from dead leaves; adults active fliers, short-lived.

Buprestidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 with some bilobed segments. Antennae filiform. A very distinctive family coveted by beetle botherers the world over. 4.0mm to 10mm for the UK saproxylic species. Use a Key as Agrilus species can be tricky to identify.

Eggs are usually placed in small groups among the bark etc. and hatch within a week or two. Young larvae feed in the cambium for a while before entering the xylem. There are between three and seven instars and the adults leave a distinctive ‘D’-shaped emergence hole. Adults of many species feed on pollen or leaves and may be restricted to the host but are often independent of this, thus many species can be sampled at flowers or by sweeping suitable foliage. More information at UK Beetles.

Eucnemidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae filiform. Can be mistaken for small click beetles 3.0mm to 9.0mm. Fairly distinctive species when you’ve established they’re not clickers. Key.

Little is known about the biology of these beetles and with the exception of Melasis buprestoides they are rarely encountered. The larvae occur in a variety of habitats associated with trees e.g. among decaying wood in stumps, branches or logs etc. where they are thought to feed upon slime mould and mycelia etc. See UK Beetles for more information.

Throscidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae clubbed. A single, saproxylic species 2.5-3.3mm.Key

Little is known about the biology of these beetles. The larvae of the one saproxylic species from the UK develop under dead bark and in wood mould, probably mainly on Quercus (Alexander 2002). See UK Beetles for more information on this family.

Elateridae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae filiform. A very distinctive family. The saproxylic species range in size from 5.0mm to 18.0mm. Some are fairly easy to identify to species, but the genus Ampedus can be very tricky. Key.

The larvae of these beetles feed on wood or other saproxylic insects. The majority of species develop over two years. See UK Beetles for more information.

Lycidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 with some bilobed segments. Antennae filiform. A small, distinctive group of beetles. They range in size from 5.0mm to 13.0mm. Key.

Adults generally have a short season and are rarely encountered. The diet of most is unknown but it is thought that larvae feed on microorganisms or the metabolic products of fungi within the host material, they are variously quoted in the literature as feeding on slime moulds, fungi, fermenting plant juices or that they may be predaceous. Adults are variously quoted as predaceous or as pollen, nectar honeydew or sap feeders and short-lived species may not feed at all. See UK Beetles for more information.

Cantharidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 with some bilobed segments. Antennae filiform. The squishiest of beetles. The saproxylic species are between 2.0mm and 7.0mm.

Many Malthodes species, which are tricky to identify. Key.

Larvae of Malthininae probably all develop in decaying branchwood or heartwood.

Dermestidae

Tarsi 5,5,5, but may look like 5,5,4. Antennae with club. Four saproxylic UK species 1.5mm to 6.0mm.

Fairly straightforward to identify if specimens are in good condition. Key.

The larvae of these species live in the crevices beneath dead bark on the trunks of large old living oak Quercus trees, or under the dry loose bark of dead standing oaks, where they are associated with the webs of the larger bark-frequenting spiders. They feed on the remains of insects eaten and left over by the spiders; and pupate within the larval skin, which splits along the back, and affords some protection.

Bostrichidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae clubbed. 2.5mm to 7.0mm. Key.

Developing in dead, hard timber continuously until interior reduced to powder. See UK Beetles for more information on this family and the two species included here.

Ptinidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae filiform or pectinate. 1.7mm to 9.0mm.

A varied family and some species have extreme sexual dimorphism. Key.

More information on this family at UK Beetles.

Lymexylidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae filiform or serrate. 6.0mm to 16.0mm.

Very distinctive beetles and easy to identify to species, although there is extreme sexual dimorphism and they can vary hugely in size.

Very interesting biology as they ‘farm’ fungi (Endomyces hylecoeti for Hylocetus dermestoides) in tunnels in dead and decaying wood. Often large aggregations of the larvae in suitable habitat, which give away their presence by the accumulation of piles of wood dust beneath the burrow entrances. I’ve written more about these here.

Phloiophilidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae clubbed. 2.5mm to 3.3mm.

A single, fairly distinctive species.

An autumn species, developing in fungus Phlebia merismoides, which grows on the bark of dead boughs and branches of various broad-leaved trees and shrubs.

Trogosittidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae clubbed or expanded. 4.0mm to 7.0mm.

Distinctive beetles and fairly easy to identify to species.

Nemozoma elongatum is a predator that occurs under bark and in the galleries of bark beetles.

Ostoma ferrugineum adults occur from April to June or a little later, they are fungivores, occurring under bark on dead trunks of large Pines that are infested with the bracket fungus Phaeolus schweinitzii. The larvae feed on decaying wood and fungi in Scot’s Pine with extensive rotten xylem infested with Phaeolus or Fomitopsis pinicola.

Thymalus limbatus generally occurs in long-established deciduous woodland where adults live under bark near to the larval host material and larvae live among or under bark or within fruiting bodies of various polypore basidiocarps where they consume mycelia and spores. See UK Beetles for more information.

Cleridae

Tarsi 5,5,5 or 4,4,4, but always with some bilobed segments. Antennae expanded or clubbed.

Distinctive beetles and fairly easy to identify to species, although the two Thanasimus species are very similar. Key.

Generally feed both as adults and larvae on insects both within the wood and on the surface. The primary prey are ptinids and scolytids. Adult clerids generally feed on other beetles while the larvae feed on other larvae, wandering the galleries to do so. Some larvae are voracious feeders able to consume several times their own body weight daily. More information at UK Beetles.

Dasytidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple. Antennae filiform or serrate. 3.5mm to 5.2mm.

The genus Dasytes can be tricky. Key.

Larvae predatory, some associated with dead timber, although in some cases perhaps only as a pupation site. See UK Beetles for more information.

Malachiidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 simple, somtimes lobed. Antennae filiform or serrate.

Can be tricky to identify. Key.

The larvae can be among dead wood or under bark where they inhabit galleries and predate other insects, although some species only use deadwood as a pupation site. See UK Beetles.

Sphindidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 simple. Antennae clubbed. 1.2mm to 2.0mm.

So far as is known all species are associated with slime mould sporocarps, both adults and larvae feed upon spores and fruiting-body tissues and all stages generally remain near to or within the host, although during dispersal adults may be found in a variety of situations, and during the winter may remain under bark or among wood debris or leaf litter. See UK Beetles.

Biphyllidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 simple. Antennae clubbed. 3.0mm to 4.4mm.

Two similar species. key.

Biphyllus lunatus is usually associated with the fungus Daldinia concentrica, which grows mainly on ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and much less often on other broadleaf trees such as alder (Alnus) and birch (Betula), adults occur year-round and are rarely seen away from the fungus and so may be under-recorded.

Diplocoelus fagi occurs in deciduous woodland and wooded parkland and gardens etc, and is associated with various fungi on a range of trees; more especially oaks, maples, lime and elm but also many others. Adults are nocturnal and usually occur in the vicinity of fungus, they are present year-round although they never seem to peak in numbers.

See UK Beetles for more information.

Erotylidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 or 4,4,4 with some bilobed segments. Antennae clubbed or filiform. 2.2mm to 6.5mm.

A fairly distinctive family. See Mike Hackston’s key.

Adults and larvae of most species feed on the fruiting bodies of various fungi. A wide range of wood decay fungi are utilized, from agaricoles to polyporales, but each erotylid species seems to be specific to a certain group. Development is usually rapid in these often ephemeral food sources and the larval stage passes quickly; two weeks from egg to pupa is not uncommon. See UK Beetles for more.

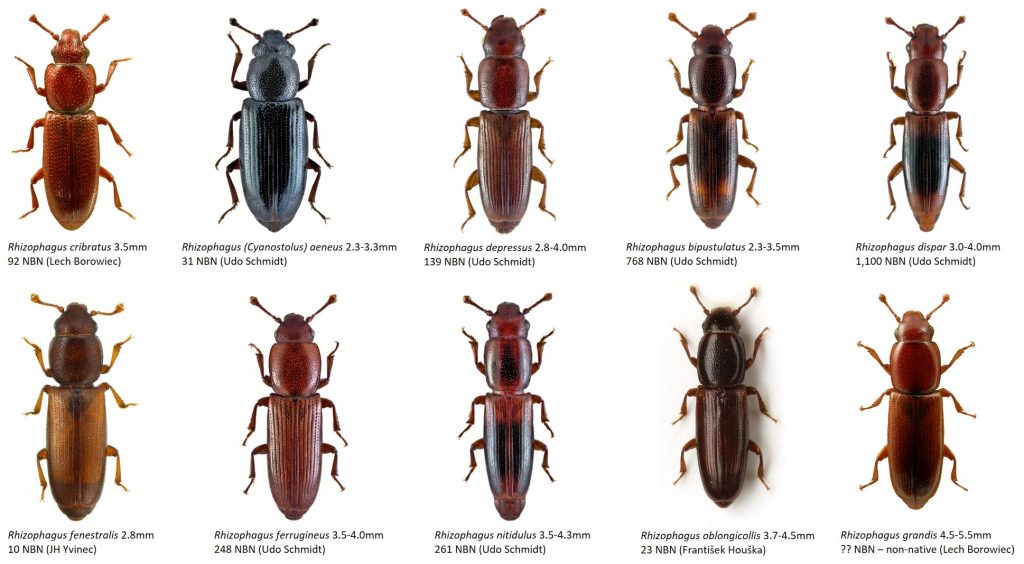

Monotomidae

Tarsi 4,4,4, somtimes lobed. Antennae clubbed. 2.3mm to 5.5mm. Key.

Larvae feed on larvae of other small beetles, including certain scolytid bark beetles; in damp conditions where there is mould or sap. See UK Beetles for more information.

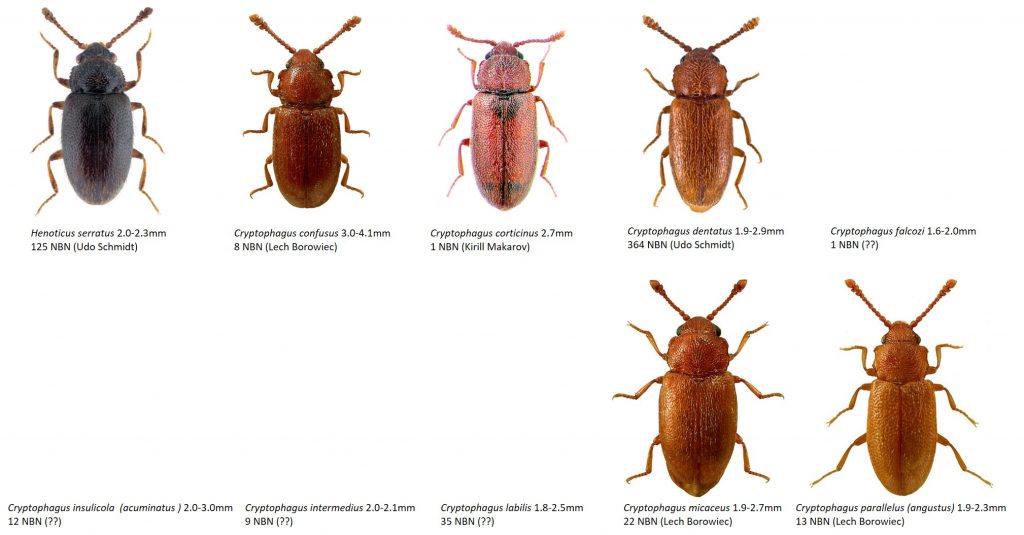

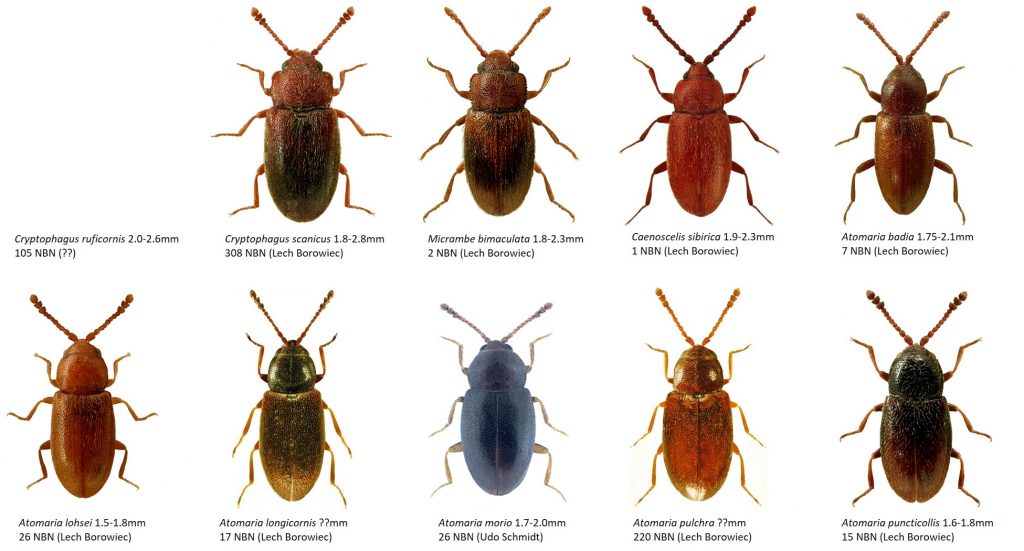

Cryptophagidae

Tarsi 5,5,5 or 5,5,4 simple or 4,4,4 with some bilobed segments. Antennae clubbed. 1.5mm to 4.1mm.

Several very similar species here. Key.

Generally associated with decaying vegetable matter infested with fungal growth upon which the larvae feed. Atomaria live among mouldy vegetation or, less often, among fungi on trees, in dry dung or under bark. Many species of Cryptophagus may also be found under bark. See UK Beetles for more information.

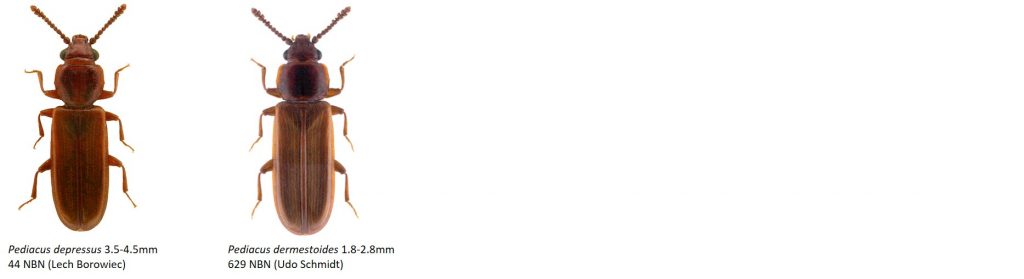

Silvanidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 with some bilobed segments. Antennae clubbed. 2.4mm to 7.0mm.

Fairly distinctive beetles, but the Silvanus species are all quite similar. Key.

Larvae predators on other insect larvae beneath bark on deadwood. See UK Beetles for more information.

Cucujidae

Tarsi 4,4,3 or 5,5,4 or 5,5,5. Antennae filiform or clubbed. 1.8mm to 4.5mm.

Two very similar species. Key.

Adults generally occur in groups and both species may be found together. The larvae are predacious while the adults are thought to be mostly fungivorous. Adults are crepuscular and nocturnal and fly well, they may be found at sap, fungus and mould on standing timber and logs. See UK Beetles for more information.

Laemophloeidae

Tarsi 4,4,3 or 5,5,4 or 5,5,5. Antennae filiform. 1.5mm to 4.5mm.

Distinctive beetles. Key.

Occur under the bark of both deciduous and coniferous trees, and are thought to be fungivores although some occur in the galleries of other bark beetles and are predaceous. The larvae of some Cryptolestes species are unique among insects in having prosternal silk glands with which they spin a cocoon. See UK Beetles for more information.

Nitidulidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 usually with bilobed segments. Antennae clubbed. 1.75mm to 8.0mm.

The genus Epuraea will make you weep into your weak lemon drink. Lots of very similar species in this genus. Glischrochilus can be tricky too. Keys.

A number of species are attracted to sap flows, especially during fermentation; at freshly cut stumps, sickly trees attacked by bark beetles and Hylecoetus, as well as exudations caused by the wood-boring larva of the goat moth Cossus. See UK Beetles for more information.

Bothrideridae

Tarsi 4,4,4 simple. Antennae clubbed. 2.8 to 4.5mm.

All dark, elongate often-shining species. Key.

Very little is known of their biology but both adults and larvae generally occur in the same situations. Thought to be subterranean – associated with roots and tubers. Some occur among the surface soil beneath damp logs etc. See UK Beetles for more information.

Cerylonidae

Tarsi 3,3,3 or 4,4,4 simple. Antennae clubbed. 1.7mm to 2.6mm.

Three very similar species. Key.

Under bark on both coniferous and broad-leaved trees in all stages of decay including fallen branches and decaying logs in just about any situation where both adults and larvae are thought to feed on fungal hyphae and spores etc. and slime-moulds. See UK Beetles for more information.

Endomychidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 simple or 3,3,3 with some segments bilobed. Antennae clubbed or filiform. 1.5mm to 6.5mm.

Two similar species and one other, very distinctive species. Key for the two tricky species.

Both adults and larvae may feed upon large fruiting bodies, graze smaller ones or consume mycelia, some feed on spores and some have been observed feeding upon lichens. See UK Beetles for more information.

Corylophidae

Tarsi simple. Antennae clubbed. 0.6mm to 1.0mm.

Two tiny, easily overlooked beetles.

It is thought that all corylophids are fungivores both as larvae and adults, feeding and developing on hyphae and spores of a wide range of species but mostly Deuteromycetes and Ascomycetes in habitats rich in decaying organic matter e.g. leaf-litter and compost or under bark and among decaying wood. See UK Beetles for more information.

Latridiidae

Tarsi 3,3,3 simple. Antennae clubbed. 1.3mm to 2.6mm.

Small and tricky with lots of similar looking species. Key.

So far as is known both larvae and adults of all species feed exclusively on fungi. Most are associated with various fungi; Phycomycetes, Deuteromycetes and Ascomycetes, and some e.g. Enicmus feed on the spores of Myxomycetes. On the whole, their biology is very poorly known. See UK Beetles for more information.

Mycetophagidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 simple. Antennae clubbed or filiform. 2.2mm to 6.0mm.

Key for the tricky species.

The larvae and adults of almost all species feed on the fruiting bodies of various fungi developing on trees and fallen timber, many undergo their entire life-cycle within such fungi and vary large populations may develop although they are rarely seen by day, careful searching by night will often reveal the adults in crevices around the fungi or even on the surface, and on warm and humid nights they may disperse across the surface of logs etc and are easily spotted. See UK Beetles for more information.

Ciidae

Tarsi 3,3,3 or 4,4,4 simple. Antennae clubbed. 1.2mm to 4.0mm

Nondescript brown or black beetles and difficult to identify with the exception of a couple of species. Key. Even with the key I find these very hard.

Associated with the fruiting bodies of a wide range of saproxylic fungi, mostly Polyporaceae but also Corticiaceae and others; they are not generally found on terrestrial forms as the fruiting bodies tend to be soft and short-lived. Adults may sometimes be found beneath bark without any obvious fungal association but this is not common and most species are rather specific regarding host choice although a few are more general, and many species of fungi have a specific ciid fauna associated with them. See UK Beetles for more information.

Tetratomidae

Tarsi 5,5,4 simple. Antennae clubbed. 3.2mm to 6.0mm.

This family itself is very difficult to define as many of the species are superficially very similar to those of several other tenebrionoid families, more particularly the Melandryidae, Mycetophagidae, Scraptiidae and Tenebrionidae.

Both Adults and larvae are thought to be fungivores, feeding and developing on the fruiting bodies of wood-rotting Hymenomycete fungi but more especially Polyporaceae and Tricholomataceae, adults feed on the surface while larvae burrow through the tissues. See UK Beetles for ore information.

Melandryidae

Tarsi 5,5,4 with some bilobed segments or 5,5,4 or 4,4,4 simple. Antennae filiform. 2.5mm to 16.0mm.

This is a tricky family with several species that look superficially like representatives of other beetle families. Key.

The majority of species live in and around bark crevices, under loose bark, in decaying wood or in fungi. The majority of species are nocturnal and, while a few adults will sometimes visit flowers in bright sunshine, in general members of the family are seldom seen. The larvae of most species live within the dead wood of stumps or fallen timber and feed on invasive fungi although a few species feed directly in the fruiting bodies of tree fungi. See UK Beetles for more information.

Mordellidae

Tarsi 5,5,4 simple. Antennae filiform. 2.7mm to 8.5mm.

The smaller members of this family can be mistaken for the Scraptiidae (see below). Generally difficult to identify to species. Key.

For a long time some species were thought to prey on other insects but there is no convincing evidence that either larvae or adults are predatory; adults are known to feed on pollen and possibly other flower parts, and some species are rarely found away from flowers. The larvae of the saproxylic species are known from fungi and decaying wood. See UK Beetles for more information.

Zopheridae

Tarsi 4,4,4 or 3,3,3 simple (rarely 5,4,4). Antennae clubbed. 2.5mm to 7.0mm.

There are a couple of species in this family that can’t really be mistaken for anything else, but the genus Synchita is tricky.

Adults and larvae of Colydiini generally are known to be predatory on sub-cortical larvae and eggs etc. as well as being fungivorous in the early larval stages. See UK Beetles for more information.

Tenebrionidae

Tarsi 5,5,4 usually simple (front tarsi may be bilobed). Antennae filiform or clubbed.

A varied bunch in form and lifestyle with several species that can be mistaken as members of other families. Key. See UK Beetles for more information.

Oedemeridae

Tarsi 5,5,4 with some bilobed segments. Antennae filiform. 6.0mm to 18.0mm.

Conspicuous beetles although some of them can be tricky to identify to species. Key.

Generally, the ecology of these beetles is poorly known. The saproxylic species lay eggs under bark or among decaying wood. The larvae emerge from the deadwood, drop to the ground and burrow into the soil to complete their life-cycle feeding on roots. See UK Beetles for more information.

Pythidae

Tarsi 5,5,4 simple. Antennae filiform. 7.5mm to 16.0mm.

A single, large species that could be mistaken for a tenebrionid.

Under fungoid bark on dead pine Pinus. Little is known about their ecoogy. The larvae are variously reported as predatory, xylophagous or detritivores. See UK Beetles for more information.

Pyrochroidae

Tarsi 5,5,4 simple. Antennae filiform. 7.0mm to 20.0mm.

Large, conspicuous and unmistakable. Key.

Eggs are laid in small batches and the unmistakable larvae will develop in groups under bark feeding upon decaying bark, dead insects and their excrement and microorganisms living in among the detritus although at high densities they are known to become cannibalistic. Larvae develop over several years and in habitats where host material is abundant and the beetles become common there may be larvae of several generations present under a single area of bark. Adults are predatory, feeding on a variety of small insects etc. among foliage or on flowers and they will also consume pollen. See UK Beetles for more information.

Salpingidae

Tarsi 5,5,4 hind tarsi simple. Antennae filiform. 1.5mm to 4.5mm.

A family with some species that can be mistaken for representatives of other families. Key.

Mainly live under bark on deadwood, though some in small branches and twigs, where adult and larva prey on other insects. See UK beetles for more information.

Aderidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 (may look like 4,4,3) with some weakly bilobed segments. Antennae filiform. 1.5mm to 3.0mm.

A small group of small beetles. See the key, although if you get to this family the species are easy to separate.

Larvae in decaying wood, particularly in red-rot. See UK Beetles for more information.

Scraptiidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 simple or 5,5,4 with some bilobed segments. Antennae filiform. 2.3mm to 4.0mm.

I find these hard to identify, but take a look at Mike Hackston’s key and have a crack.

Develop in rotten wood (soft decaying xylem in old Oak, Beech and Hawthorne etc. ). Adults fairly indiscriminately on flowers and sometimes on foliage. See UK Beetles for more information.

Cerambycidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 with some bilobed segments. Antennae long and filiform. 2.5mm to 45.0mm.

Among the most adored of beetles. Often big and conspicuous, most of the species in this family are associated with dead wood. Most are easy to identify, but there’s considerable variation in many species, so check a key if you’re not sure.

The larvae develop within all parts of the host; leaves, twigs and branches, seeds, trunks and roots. Most species take between one and three years to complete the life-cycle although in warmer climates this may be complete in two or three months. Typically, the females oviposit in damaged wood, bark-crevices or in the soil around the roots or in fallen timber and the larvae emerge after a week or two and immediately begin to feed upon the host material, either among the softer cambium or by boring into stems. Some bore directly into roots or into the soft xylem of decaying logs etc., as they grow they bore deeper into the wood producing often characteristic tunnels, but in general they remain near the surface. See UK Beetles for more information.

Anthribidae

Tarsi 4,4,4 with some bilobed segments. Antennae filiform or clubbed. 1.7mm to 13.0mm.

A small, very distinctive group. Fairly straightforward to separate the species. Here’s a key.

Most species are fungivores both as adults and larvae, either consuming fruiting bodies directly or living among decaying vegetation and feeding upon associated mycelia and hyphae; larvae generally live within decaying trunks, branches or stems of a wide range of both Angiosperms and Gymnosperms and rely on associated fungi to reduce the plant tissue to food that can be consumed. See UK Beetles for more information.

Curculionidae: Dryophthorinae

One very rare and distinctive species. 3.0-4.0mm.

At interface of hard oak Quercus timber with red-rot, also in beech Fagus, and often associated with the ant Lasius brunneus. The larvae are thought to be wood-feeders, but the biology of this species is poorly known. See UK Beetles for more information.

Curculionidae: Platypodinae

One, distinctive species that seems to be becoming more common. 5.0mm to 7.0mm.

Strongly attracted to smell of fermenting sap, arriving at freshly split or felled timber; male appears first and bores into a crack or crevice, female arriving later and entering tunnel; both emerge to mate, then female continues boring, producing white & splintery bore-dust, and eggs laid in main tunnels; larval period 1 year normally, and graze on lining of tunnel which is composed of small fragments of wood on which the fungal growth occurs; adults and larvae in galleries extending deep into heartwood, feeding on fungi cultured in borings; mainly oak Quercus, but also beech Fagus and other broad-leaved trees. Widespread in southern England and Wales, but absent from far south-west. See UK Beetles for more information.

Curculionidae: Scolytinae

A diverse group, many of which can be a challenge to identify. 1.1mm to 6.5mm.

Species feeding on wood (xylem) and/or phloem are usually restricted to one or a few hosts, whereas those which carry their own symbiotic fungi which break down the xylem (ambrosia beetles) may colonize a larger range of hosts. Many species have been imported in timber and some have become established. A number are more strictly phytophagous, their larvae feeding in the still living inner bark of stressed or moribund stems or branches, but these have been included in the list nonetheless. See UK Beetles for more information.

Curculionidae: Cossoninae

A distinctive sub-family of weevils. 2.5mm to 9.0mm.

Associated with decaying trees and fallen timber, often where fungus infestations are present, where the larvae develop as they bore through damp wood. See UK Beetles for more information.

Curculionidae: Cryptorhynchinae

Distinctive beetles in this habitat, but the species can be hard to separate. 2.0mm to 3.6mm. Here’s a key

Little is known of their biology but breeding is thought to occur in the spring with larvae developing in the bark on twigs and small branches and producing new-generation adults in the autumn. See UK Beetles for more information.

Curculionidae: Mesoptiliinae

A distinctive sub-family, but several, very similar species which can be tricky to separate 2.4mm to 6.2mm. Here’s a key.

These beetles have a short season during late spring and early summer, eggs are laid in or below bark and larvae mine beneath the bark or in the xylem, pupation occurs in the tunnels and adults remain in the wood, often in numbers in tightly packed borings. Several species are widespread and common and should soon be found by beating etc. See UK Beetles for more information.

Curculionidae: Molytinae

Large, distinctive species in this sub-family. 2.8mm to 13.0mm. The two Pissodes species are similar.

In conifer plantations, Hylobius abietis feed on the phloem and browse the bark of stems and lateral shoots of seedlings, which can lead to the deformation or death of trees. The larvae feed on tissues of the inner bark and the cambium of pine stumps. Pissodes spp. are associated with pine woodland where the larvae develop in dead wood or cones. Trachodes adults are associated with various deciduous trees, particularly oaks, where they occur under bark or among nearby leaf-litter. Larvae develop among damp decaying wood. See UK Beetles for more information.

Gallery

Gallery of all the images shown above.

Leave a Reply