6 Billion Species

*A shorter version of this article was published as The Spice of Life in BBC Wildlife Magazine (Issue 435, February 2018)*

Futurists who have read too many comics and billionaire technologists fuel the human ego with visions of interstellar travel and terraforming the cold, dead dust of Mars. Theirs is a jaded view of the Earth, a planet that has nothing left to offer, from which all the mystery has been wrung. Nothing could be further from the truth. We have barely scratched the surface of understanding our beautiful world, from how many species we share it with to how they all interact.

To date, we have formally described around 1.6 million species of living thing broadly divided between three domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes (Animals, Plants, Fungi and Protists). How many more are there? This question is one of the most fundamental in science, but answering it is far from straightforward. The closer we look at life on earth, the more complex and confusing it becomes. Under scrutiny, even the term ‘species’, is a bit flaky (see What is a species?).

Regardless, answering this question has become something of a cottage industry in biology with almost as many estimates as species, some being pumped out by scientists who have little understanding of whole organism biology. For some reason, recent estimates of around 10 million species seemed to be meaty enough to satisfy the masses, but they make some enormous assumptions and more-or-less disregard the most diverse groups of organisms. Using a new approach to remedy some of these issues, a team at the University of Arizona have come to the following conclusion:

“there are likely to be at least 1 to 6 billion species on Earth. The new Pie of Life is dominated by bacteria (approximately 70–90% of species) and insects are only one of many hyperdiverse groups.”

This is a little bigger than previous, high profile estimates, but it embraces the enormous bacterial diversity we find wherever we look, not to mention parasites and the hyper-diversity of insects, mites and nematodes. Animals account for 163 million species of this whopping estimate. This might seem huge, excessive even, but there are plenty of reasons why it is near the mark.

The Earth is big

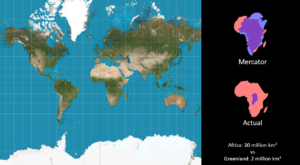

It is now so easy to travel from continent to continent that we tend to forget how big the Earth is. Not only that, but popular maps of the surface of our planet stretch and distort, so much so that the landmasses are not shown as they really are. The Mercator projection, probably the most popular depiction of Earth’s surface shows Greenland and Africa roughly equal in size, but Africa is actually 15 times the size of Greenland (30 million km2 vs 2 million km2).

This is an enormous area and Africa like everywhere else has many difficult to reach or overlooked areas where few biologists have ever been. Changing scale, think about the structural complexity of a forest – the water-bodies, soil, roots, detritus, stems, boughs, leaves, bark and seeds. The number and variety of niches in a forest is mind-boggling. Some of my work in Peru involves getting a handle on this – exploring the extraordinary diversity of animals that live in the unfurling leaves of a couple of species of understorey plants.

Of course, the ocean is a huge unknown, but even here we underestimate. It’s often said that we’ve explored around 5% of the ocean, but this refers to the seabed and is probably an exaggeration. We have to remember that the whole volume of the ocean is a habitat, and we’ve explored less than 1% of it.

Most animals are small

Not only is the Earth enormous, but most animals are small – much smaller than us, so unless we’re specifically looking for them we simply don’t notice them. Scuttling behind the skirting board in your house, patrolling the dense tangle of vegetation in a forgotten corner of your garden and navigating the labyrinthine channels between the sand and sediment particles of the sea-shore is a marvellous menagerie of small animals. Take the constellation of sub-1 mm animals that live between and on the sediment grains on the seabed – the meiofauna. In one handful of this habitat there might be thousands of individuals and representatives of more animal lineages than in an entire tropical rainforest.

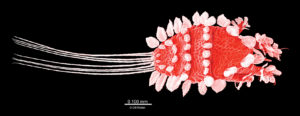

Our appreciation of life on Earth is completely skewed by our own size, but size has little or no bearing on biological importance. As the eminent parasitologist, Bob Kabata, once said:

“had the copepod been the size of a cow, the tip of its first antenna would have become a topic for exhaustive studies.”

We’re drawn to similar animals

Getting to grips with animal diversity is further confounded by the fact that we’re drawn to those animals we feel an emotional attachment to, either because of the way they look or the way they behave. Typically, these are mammals – cute wet noses, doe eyes, etc. However, many animals are faceless and there are lots that don’t even have a head. The appearances and lifestyles of most animals are very alien indeed, so we have trouble forming any sort of emotional bond with them. It’s much easier to identify with a lioness and the challenges she faces nurturing her cubs than it is to form any sort of emotional link with a faceless crustacean that spends most of its life attached to the eye of a fish.

Few things are what they seem

The often very strange outward appearance of animals also impedes our attempts to work out what’s what. In part this is linked to the common preconception of how evolution works. To many people, evolution is just a one-way, linear event where simple forms give rise to increasingly complex ones, so it has become ingrained that simple forms must be primitive. In reality, evolution just as easily moves in the other direction and in adapting to a particular niche an animal can progressively lose many, sometimes all, of its complex features. These so-called degenerates, charming characters such as tongue worms, slime animals and thorny-headed worms had generations of zoologists scratching their heads and it was only the ability to sequence DNA that revealed their true heritage.

Heaped on top of this secondary simplification and to make things even more complicated, nature can trick us at every turn with a huge variety of doppelgangers and deceivers. Lots of animals look very similar even though they aren’t closely related, either because they happen to live in similar ways and have converged on a similar appearance.

Cryptic diversity

The outward appearance of an animal also conceals a huge amount of cryptic diversity; where something that looks like one species is actually several, identical-looking species. Only by delving into natural history and DNA can we reveal the true extent of cryptic diversity. This is a burgeoning area of research in all fields of zoology. A beautiful example of just how much diversity is hiding in plain sight is a parasitoid wasp from Costa Rica that was assumed to be one species. Entomologists looked at the DNA and ecology of this wasp – exactly where and how it lives – to reveal it is actually a complex of 36 outwardly identical species, all of which live very distinct lives.

The challenges of finding

There are species waiting to be discovered all around us, but it is the tropical forests and coral reefs where we find the greatest concentrations of life. Going to these places and documenting their fauna in a systematic way is often difficult. For me, the canopy of a primary tropical forest is most tantalising of all – it’s there within easy reach, but exploring it freely without disturbing it excessively is next to impossible. Most of the life in these forests is up in the canopy.

Some regions are out of bounds because of war and political strife, while others are just extremely remote and hostile once you’ve managed to get there. Exploring the deep-sea is as challenging as going out into space, with a similarly hefty price tag.

Most species are rare

Even if you manage to get to your destination there’s no guarantee you’ll find much of interest because most species are rare or are only conspicuous for a small proportion of their life. This seems to be at odds with what we see. We’re surrounded by animals. This is true, but look a little closer and the reality of this ubiquity is vast numbers of a few extremely common species. A mantisfly I found in the forests of northern Myanmar turned out to be a new genus and I’d happily wager that I could go back to that same forest and spend a month looking just for that animal and never see it again. Likewise, a moth I found in that same forest was first described in 1894, but in more than 120 years it has been seen only three times. Perhaps these species spend most of their time in the canopy and if you were able to search that habitat with ease you would find more of them, but I think the truth is that many species just live at extremely low population densities.

The challenges of describing

Even if you find lots of interesting things, this is just the thin end of the wedge and where the fun begins. These specimens need to be compared to what else exists in the disparate collections around the world by someone who has spent years working on that particular group of organisms. Looking at the outward appearance of an animal is all well and good, but we need to go deeper than this – we need to read some of its DNA and we need to know where and how it lives. It’s this latter part that is the real sticking point. The vast majority of the 1.5 million formally described species are little more than a name; nothing is known about their ecology. The mantisfly and moth from Burma are ‘known’ to us now, but their ecology is a mystery. Where exactly do they live? What do they eat? Who eats them? Only by answering these questions can we begin to really understand life on Earth.

Few people looking

There are very few people working at the front line of discovering species and understanding how they live. This is because there’s not a lot of funding for this sort of work, it can be extremely painstaking and it’s sometimes seen as an academic backwater, which is a real travesty.

Consider the three most diverse groups of animals: insects, mites and nematodes. Between them, they number in the many millions of species. There are quite a few entomologists out there, but we’re spread very thin. Just to give you an idea of the scale of the problem, there are more species of weevil and rove beetle than there are vertebrate, and we’ve only nibbled the edges of these beetle families. The mites and nematodes fair even less well. Their diversity perhaps surpasses that of insects, but worldwide there are only a handful of scientists studying their diversity and ecology. As these animals are abundant in every habitat there can be no interactions in the living world where their influence is not felt, but we know next to nothing to about them.

A planet bristling with life

Numbers to one side, we need to remember that the Earth is still full of mystery and that’s something we should all find heartening and exciting. We’re living in a new golden age of discovery, as technology is enabling us to look at the natural world in new ways, but with every bit of habitat that falls to the chainsaw or disappears under the plough or concrete, species are lost to us forever, most before we ever got a chance to describe and understand them, impoverishing nature and ultimately ourselves.

Pragmatically, every species is a component of the natural systems that keep us alive and we can only understand these systems when we know the components. Evolution has solved the greatest of problems and by studying life on earth I believe we will find solutions to many of the challenges that face humanity.

More intrinsically, as intelligent beings it is our duty to protect and understand our fellow organisms not only for their own sake but also because of what they tell us about the phenomenon of life. In a cold universe we are the privileged inhabitants of a beautiful, living planet and it is this we need to cherish above all else.

Box: What is a species?

This is a tricky question and there’s no clear-cut answer. The most widely used definition is based on the biological species concept proposed by Ernst Mayr in 1942: “Species are groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations, which are reproductively isolated from other such groups.” This is well known and has some intuitive appeal, but it’s very limited and is biased towards animals. For example, we cannot apply it to bacteria and many other organisms where asexual reproduction is the norm. With that said, these organisms still exist as discrete groups with shared characteristics, so the definition needs to be tweaked. There are currently 32 different species definitions and there isn’t one that applies to all life. We have to remember that the concept of a species is a useful tool, but one that we invented. Our minds thrive on order – neatly arranged compartments – and we seek this when making sense of the natural world, but nature is dynamic and fuzzy with poorly defined boundaries. Regardless of the organisms in question, lineages are continually splitting and rejoining over time – a bit like the braided flow of a river in a delta – and this is the only commonality we can find.

Further reading

Bickford D et al. Cryptic species as a window on diversity and conservation. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2006;22:148-155.

Chang ES et al. Genomic insights into the evolutionary origin of Myxozoa within Cnidaria. PNAS 2015;doi/10.1073/pnas.1511468112.

Condon MA et al. Lethal Interactions Between Parasites and Prey Increase Niche Diversity in a Tropical Community. Science 2014; 343 (6176):1240-1244.

Huber JT and Noyes JS. A new genus and species of fairyfly, Tinkerbellanana (Hymenoptera, Mymaridae), with comments on its sister genus Kikiki, and discussion on small size limits in arthropods. Journal of Hymenoptera Research 2013;32:17-44.

Larsen BB et al. Inordinate fondness multiplies and redistributed: the number of species on Earth and the new pie of life. The Quarterly Review of Biology 2017;92(3):229-265.

Liu X et al. A new genus of mantidflies discovered in the Oriental region, with a higher-level phylogeny of Mantispidae (Neuroptera) using DNA sequences and morphology. Syst Entomol 2014, 40(1):183-206.

Rabinowitz A. Ground Truthing Conservation: Why Biological Exploration Isn’t History” Conservation Magazine 2002;3(4):20–25.

Rundell RJ and Leander BS. Masters of miniaturization: Convergent evolution among interstitial eukaryotes. Bioessays 2010;32:430–437.

Smith MA et al. Extreme diversity of tropical parasitoid wasps exposed by iterative integration of natural history, DNA barcoding, morphology and collections. PNAS 2008;105:12359–12364.

Leave a Reply